![]() Rhondak101

Rhondak101

4/7/2013

![]()

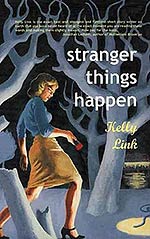

When I read the review of Kelly Link's Stranger Things Happen (2001) on Salon.com, I was sure that I would love this collection of eleven short stories. According to the reviewer, Laura Miller, the stories are a mixture of modern horror and fantasy. Unfortunately, I was not as taken with this collection as Miller was. However, they are intriguing and clever.

Let's start with intriguing. I keep bringing them up in conversation whenever I can. I want to tell people about the stories—sometimes to tell them about a clever idea, sometimes to share a sentence with them, and sometimes to complain about them. Even though the stories are clever, they are not all satisfying. Often a story can get by with shortcomings in character and plot just because it is so cleverly written. In my opinion, only a few of Link's stories can get by on cleverness alone. The others left me frustrated or simply scratching my head.

After days of struggling with how I feel about these stories and talking to others, I have come to the following conclusion: Link's stories reflect a turn to postmodernism in speculative fiction (a convenient umbrella term for the moment), and they demonstrate what is both good and bad in postmodernism. Now, I say this without irony or derision. I know the term "postmodern" gets thrown around much too much these days. (Here's a fun video about this with some R-rated language.) Until I read Stranger Things Happen, I would have told you that postmodernism is like pornography: "I know it when I see it." However, this book took me unawares; shame on me, a lover of postmodern mysteries not to recognize postmodern traits immediately in other genre writing. Like some postmodern writers, Link uses other texts, recycling older stories; she plays with words and creates intricate, crafted sentences that revel in their own artistry. Her narrators are simultaneously reliable, unreliable, vexed, and all the other things that make postmodern narration a challenge for readers. These are her strengths. However, as I said above, plot and character development often go by the wayside just like in some postmodern texts. The stories are puzzles for the readers to put together rather than pictures for them to see.

The stories that I found the weakest lacked any kind of satisfying closure. I was just as mystified at the end as I was at the beginning. They didn't even have the satisfying open-endedness of, say, A Twilight Zone episode. For example, "Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose" is a story about a dead man writing letters to his wife. He cannot remember her name or his. I was not sure what Link wanted to accomplish with her conclusion. Yet, the story is a great showcase for Link to play with language: "It really is me, by the way, although I have to confess at the moment only can I not seem to keep your name straight in my head, Laura? Susie? Odile? but seem to have forgotten my own name. I plan to keep trying different combinations: Joe loves Lola, Willy loves Suki, Henry loves you, sweetie, Georgia?, honeypie, darling." Unfortunately, for me, the pleasure of this story never goes beyond the immediate pleasure of individual sentences. They do not add up to more than the sum of their parts.

As the sentence above shows, Link is a master with lists. She has a great riff in the final story, "The Girl Detective." In this story, a group of dancing bank robbers adds objects to bank vaults rather than taking money away: "Lost pets. The crew and passengers of the Mary Celeste. More socks. Several boxes of Christmas tree ornaments. A play by Shakespeare, about star-crossed lovers. It doesn't end well. Wedding rings. Some albino alligators. Several tons of seventh-grade homework. Ballistic missiles. A glass slipper. Some African explorers. A whole party of Himalayan mountain climbers. Children, whose faces I knew from milk cartons. The rest of that poem by Coleridge. Also fortune cookies."

This passage reminded me of a masterful example of this written by Harlan Ellison. In his short story, "Shoppe Keeper" in the collection Shatterday, Ellison produces a 700+ word list of items in the shoppe. (No, I did not count. An estimate at eight words per line.): "A thirty-foot-high glass-fronted cabinet that seems to contain model toy soldiers, until the young man looked closer and saw that the models were not metal at all, but seemed to be miniaturized human beings, frozen and solidified in the moment of combat: the Battle of the Ardennes; Balaklava; Visigoths against Huns; Rough Riders against Villa; Luftwaffe and Wolf Legions at Stalingrad; the Battle of the Little Big Horn; Midway; Chosen Reservoir; the one hundred Spartans at the Hot Gates against Xerxes' millions; the French Foreign Legion at Dien Bien Phu; Spartacus and his gladiator army versus the Roman Imperial Legions. . . each soldier perfect, down to the expression of utter horror as he was whisked off the battlefield, shrunk and concretized. Polish for the True Lamp. A fragment of Christ's molar in the wafer. Stigmata kits. Packets of dried Granny's Claw. Eyes of newts. Toes of frogs. Spiderweb poultices." The reader of this extraordinary passage needs to know not only history to identify the soldiers and their battles but also something about medieval relics, Macbeth's witches, homeopathic methods to stop bleeding, and probably many other references that I have not picked up on, such as Granny's Claw. (An internet search did not help me with that one).

I love these types of lists, lists which pull from shared cultural knowledge and expect the readers to find the meaning in a place outside the text itself (if they do not bring the knowledge with them.) One of the people whom I sought out to tell about Stranger Things Happen and discuss Link's lists is my friend Mac Williams, who happens to be a scholar of Jorge Luis Borges, an important precursor of postmodernism. We decided that we want to call lists like this Borgesian because of the frequency in which they appear in Borges' stories. You can find a couple of examples in "Pierre Menard, Author of Quixote" and "The Analytical Language of John Wilkins." Mac reminded me that Neil Gaiman creates visual lists like this in Sandman, Lucien's library of never-written works, for example.

Kelly Link's postmodern cleverness is an asset when she uses it to play with cultural references. In some of these stories, the readers will marvel at the way she has disguised old stories until she is ready to spring them on the readers, who are usually still unaware of their origins. For me, this moment of recognition was usually followed by a head slap and re-reading earlier passages to see the clever clues. Link takes fairy tales, myths, and other old stories and makes them seem new. In her hands, the old stories have something to say about our world. And even when the old stories are not as well disguised and I saw the punchline coming a mile away, I couldn't help but smile and say "how damned clever." In her stories, the readers will meet Greek gods, Briar Rose, Cinderella's prince, and Imelda Marcos, living in other lives, in other worlds that not intended for them.

My favorite stories are "Flying Lessons," "Travels with the Snow Queen," and "Shoe and Marriage." To say too much about any of them would give away their underlying cleverness. "Shoe and Marriage" contains four separate vignettes that emphasize shoes as a cultural icon as well as their relationship to marriage and courtship. Since I can't say more than this, I will share Link's clever language from the second vignette on shoes and marriage:"We are sitting on our honeymoon bed in the honeymoon suite. We are in a state of honeymoon, in our honey month. These words are so sweet: honey, moon. This bed is so big, we could live on it. We have been happily marooned--honey marooned--on this bed for days."

Stranger Things Happen is the first of Link's three short story collections. The others are Magic for Beginners (2005) and Pretty Monsters (2008). Although the stories are often perplexing, my experience with Stranger Things Happen ensures that I will read these collections as well, looking for more cleverness and misdirection. I recommend this book to those of you who think you would like the lush sentences and cultural references of a Salman Rushdie or a Neil Gaiman contained in the non-linear, episodic style of a Paul Auster or an Italo Calvino. All three Link books are available at Small Beer Press. The first two are free in epub format and easier found by searching the internet than on Small Beer's site—how do they bury these things so deeply?