![]() Rhondak101

Rhondak101

2/1/2014

![]()

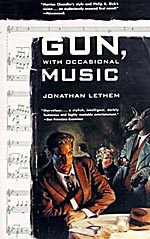

I've wanted to read Jonathan Lethem's Gun, With Occasional Music (1994) since I heard someone give a paper about it in a detective fiction panel at an academic conference several years ago. Soon after, the book was a Kindle daily deal, so it has been sitting on my virtual TBR shelf for a while now. The 35 challenge pushed me to dust it off (virtually, of course) and read it. Lucky for me, the book fulfills three other RYO challenges: Socialists, etc. (Lethem grew up in a commune in Brooklyn); The End of the World (future dystopia); and The Second Best (nominated for a Nebula).

Lethem creates a bizarre dystopian world, full of new species, who live among human society. First, there are talking animals. These so-called evolved animals seem to be creatures who grow to the size of a small human, move bipedally, and talk and think as humans. In the course of the story, we meet an evolved ape, kitten, ewe, kangaroo, and other secondary characters. These characters are interesting and fully-imagined; their difference doesn't really provide an obstacle for the reader. This cannot be said about the second group, a new form of children in this world. Lethem does not completely explain if these new "children," called Babyheads, are in addition to or instead of human children. Babyheads have mature minds but inhabit miniature and deformed bodies. They are born very smart but not emotionally stable. As they live among humans, they grow more and more resentful about being trapped in a small body "in a six foot world" (234). The sub-culture of the Babyheads is the weakest part of the book because Lethem never takes the time to explain about their appearance or function in this new society. The reader is left with many distracting questions.

If the reader can accept the evolved animals and get past the Babyheads, then the society that Lethem creates is certainly worth closer examination. At some time in the near past, there was in Inquisition, which is never explained. Yet, after the Inquisition, it became illegal to ask anyone a question. Newspapers could not write the news; they could only print captionless photos. The vocal news on the radio was limited to only a few spoken words a day. The rest of the time the "feeling" of the day's news is broadcast via musical arrangement. Televisions do not show narrative programming but abstract shapes moving to music. (I picture screen savers here).

In this world, the only people allowed to ask questions are inquisitors (the new word for police officers). Each person carries a magnetic swipe card that holds their karma points. Committing a crime or failing to answer the questions of the inquisitors costs each citizen karma points. There are also ways to regain karma, but the book is not very clear on that point. When a citizen runs out of karma, he is cryogenically frozen to serve out his term. In other words, instead of going to prison, a person goes to the freezer, and when his time is served, he is revived.

When the reader peels back all of the book's dystopian elements, this is essentially a noir novel in the spirit of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. The protagonist, Conrad Metcalf, is a P.I. (Private Inquisitor), licensed to ask questions. When one of his former clients is murdered and the prime suspect hires Metcalf to keep him out of the freezer, Metcalf enters a plot that Hammett himself could have written with corrupt inquisitors, crime bosses, junkies, femme fatales, smart aleck bartenders, and thug wannabes. Lethem's language evokes Chandler's: "The feeling was there before I tuned in the musical interpretation of the news on my bedside radio, but it was the musical news that confirmed it: I was about to work again. I would get a case. Violins were stabbing their way through the choral arrangements in a series of ascending runs that never resolved, never peaked, just faded away and were replaced by more of the same. It was the sound of trouble, something private and tragic; suicide, or murder." (2-3). Metcalf's repartee with the inquisitors who try to warn him off the case is so dry and laconic it seems as if Bogart could have uttered it, if, of course, the censors would have allowed the word "dickface" to appear in The Maltese Falcon.

Just like Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade, Metcalf is a special kind of philosopher/hero. He tells his client: "I learned a long time ago that my job consists of uncovering the secrets people keep from themselves as much or more than the ones they keep from each other" (47-48). Metcalf sees his cases as more than puzzles to be solved; they are metaphysical events that send ripples though the universe: "A murder didn't happen in a void, like some kind of hiccough. It was the outcome of an inexorable series of past events climaxing in the act, and with repercussions stretching into the future far beyond the usual inquisition" (41). And thus, by the end of the novel, justice is served in the same type of messy, somewhat distasteful way that Marlowe wraps up his cases. Metcalf is a hero, but not a law-abiding one.

I am a big fan of noir novels and movies, and this one did not disappoint me as a fantastic version of the genre. Two final points that I hope will further serve to recommend the book to you. First, the mystery is solved and solved in a way that is true to the culture and society that Lethem creates. While the murder's "past events" of greed, lust, and jealousy are appropriate to noir in any age, the circumstances of the murder belong inextricably to Metcalf's world. Second, the reader learns the meaning of the book's unorthodox title, and that title fits.