![]() Scott Laz

Scott Laz

6/20/2014

![]()

Along with Jack Williamson, Edmond Hamilton was an early pioneer of space opera, his galaxy-spanning space-based adventure fiction having begun appearing in the 1920s. During the 1940s, E. E. "Doc" Smith would take the Williamson/Hamilton template and ramp it up to another level, while Hamilton seemed to take a step backwards, toiling away on the formulaic Captain Future series while a new generation of writers with a greater commitment to scientific extrapolation and a more mature writing style began to dominate the field.

During this period, Hamilton's space operas would look increasingly old-fashioned, and while Smith's Lensman series was extremely popular, it's appearances alongside the fiction of Robert Heinlein and other (relatively) young writers in Astounding began to look more and more anachronistic as the '40s progressed. Old-style space opera would remain somewhat popular, with paperback reprints still appearing into the 1970s, but it was of little interest to readers who had not grown up with it, and "space opera" itself was still used as a pejorative term. (It derives from "horse opera", a nickname for formulaic westerns, and follows from the observation that much of the early magazine science fiction contained plots that could have been written for westerns, transplanted to an outer space setting.)

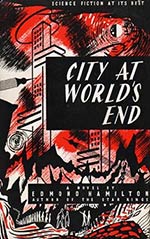

All the more surprising, then, that while E. E. Smith, whose space opera was more developed than Hamilton's, could not make a successful transition to the post-space opera field, Hamilton (along with Jack Williamson), was able to do so, remaining successful with new work into the 1960s. City at World's End is a case in point, and is an especially interesting example, as it begins with a modern (for 1951) science fiction scenario, while managing quite unexpectedly to shift gears in its second half, returning to the interplanetary adventure style more reminiscent of Hamilton's early work, and making this dichotomy work in the novel's favor.

City at World's End begins with a surprise nuclear attack—the detonation of a "super-atomic" bomb over Middletown, its name indicating its status as an archetypal middle-American town of its era. Apparently, Middletown was a nuclear target due to the secret presence of a military research laboratory, one of whose scientists, John Kenniston, is the novel's protagonist. Rather than destroying Middletown, the previously untested super-atomic ruptures the time-space continuum (or something like that), catapulting the entire town uncounted millions of years into the future, into a time when the sun is dying, the earth's core has cooled, and the human race seems to have disappeared. (Hamilton uses the term "dying Earth" numerous times in the novel, Jack Vance's novel of that title having appeared just a year earlier.)

This dying earth is too cold for long-term survival, so the Middletowners move to a nearby, long-abandoned, futuristic domed city, which is somewhat warmer, and contains machinery that might help them survive, if they can figure out how to use it. They struggle to cope with what has happened to them, and, as the novel progresses, it follows the pattern of a dystopian survival story. Kenniston and the other scientists try to understand the city's machinery, and to make contact with anyone left on Earth, while the majority of Middletowners pine for home while trying to make the best of a situation that their psychology cannot deal with.

This set-up—a 1950 Midwestern town transplanted to a far-future dying Earth—would seem to be sufficient for novelistic treatment, and Hamilton does explore the psychological and sociological ramifications, if fairly simplistically, up to a point. But then, just as it seems that the Middletowners are destined to remain on their own, and that the novel will be about their attempts to maintain the remnants of the human race on a dying planet, the story undergoes a major shift. It turns out that the transmitter that Kenniston has been attempting to operate, and which he does not entirely understand, is an interstellar device. Humanity has long since spread across the galaxy, and is now the most advanced race in a planetary Federation, having long ago abandoned their dying home planet. Now a ship has arrived from Vega to determine the nature of the transmission from Earth, and the Middletowners have more shocks in store, as they must mentally adjust to the idea of interplanetary space travel and the existence of other alien humanoid races.

The second half of the novel, then, is in more familiar "space opera" territory, as the book shifts from a post-apocalyptic dystopia into a political story with the galactic Federation as a backdrop. The plight of Middletown remains central, however, as the Federation has plans to evacuate the Middletowners to a more suitable home. Instead of being grateful for the rescue, however, the townspeople decide that they have had enough disruption of their lives, and would rather stay on their home planet, even if they have to fight for it. Such a fight would be hopeless, and the Federation is so used to having their edicts obeyed that they cannot fathom the actions of these "primitives," so the situation rapidly degenerates into a standoff.

Kenniston, the voice of reason, can understand the Middletowners feelings, but also knows that they have no chance against the Federation, and so embarks on a ship to Vega in order to try to sort out the situation. Once there, he learns that Earth has become a pawn to the political ambitions of a Federation official, and that there are other members of the Federation (ironically, several non-human races), who want to resist the heavy-handed evacuation tactics that they have also been victims of. They enlist Kenniston in a plan to force the Federation's hand by showing them that there may be another way to solve the problem of dying planets.

The conflict Hamilton sets up in the second half of the novel comes across as somewhat artificial, as it seems unlikely that, out of fifty thousand spunky Midwesterners, however admirable their dedication to their way of life, none of them (except the outsider scientists), seem to be able to face the fact that their community and, possibly, the human race would be doomed by their stubbornness. Nor can they accept the reality that there is no way they can actually fight the Federation's evacuation order, even though they have had ample evidence of their technological capabilities. And no one but Kenniston is intrigued by the possibility of traveling the galaxy in a spaceship? Hamilton presents their dedication to their community and way of life as admirable, but a rational appraisal must also deem it parochial and unreasonable.

While I wouldn't say that City at World's End is a philosophical novel, its mashing together of Midwestern conservatism with galactic space opera does bring up the question of humanity's ability to face change and the future—one of the great science fiction themes. It's difficult to know what Hamilton's view of the question would be. He seems to side with the Middletowners against the Federation bureaucracy, but he must have known that his readers, being science fiction fans, were likely to have the same reaction I (and ultimately Kenniston) did, wondering at the townspeople's emotional inability to consider the potential wonders of the galaxy that has opened up to them. Possibly Hamilton was also uneasy about the situation he set up, since he finds a way to end the novel without requiring the Middletowners to really face this reality, though he hints that the younger generation will be eager to face the future.

City at World's End is a fine example of the SF of its day. It's interesting to see Edmond Hamilton attempting to adapt to the more mature science fiction of 1950, while calling back to his 1920s space opera roots. It's almost as though, halfway through his attempt at a post-nuclear parable of the sort common in the '50s, he decided that spaceships and giant teddy-bear aliens were more fun after all. But he never loses sight of the conflicts engendered by forcing these two worlds to encounter each other, and their co-existence remains an uneasy one.