![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

10/24/2014

![]()

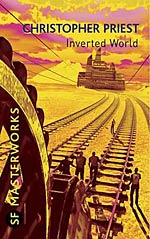

Ground that slips. Warped horizons. Variable forces. The limits to which genre fiction can be stretched and altered to accommodate its own metafictional boundaries are far and wide, yet few authors dare to test their tales against those limits. Straightforward stories of unique characters in unique circumstances carry their own appeal, but some authors move beyond that. In 1974's Inverted World, Christopher Priest manages to probe those appraising, distant boundaries, while capturing the visual imagination of his readers, and without mangling the central tale of a boy becoming a man in a city of passive incomprehension.

We see the words "mind-bending" and "mind-blowing" thrown around a lot when describing speculative fiction novels, and it's not without good reason. Most spec fic readers seek more than just a good story—they want to alter their reality, stretch their minds. But reading spec fic is a bit like mind yoga, and while there are many styles to choose from, some of them just aren't very challenging. Still, it is with great hesitation, yet utter sincerity, that I deliver the following pronouncement:

Christopher Priest's Inverted World is mind-bending. No hyperbole intended. (Although there are some hyperbolas.) (sorry.)

In his hyperbola-shaped world, Priest plays with geometry, perspective, and style, while bending both the mind and the genre. He proves that fluctuating grav is not only interesting, but is an excellent tool for literary expression and genre subversion. A description of the world is enough to deter the physics-phobes, but Priest's most significant feat of engineering is in the literary joints and struts of the tale—quadratic equations not required.

Helward Mann is the age of six hundred and fifty miles and lives in the city of Earth. Having recently come of age, he must leave the confines of his city to train as a guildsman, apprenticing for the different guilds that contribute to the welfare and movement of the city. His first apprenticeship involves the construction of a set of tracks, on which Earth must be laboriously winched closer to the ever-moving "optimum." ("It takes the city about ten days to cover a mile... and in a year it will cover about thirty-six and a half" p. 41.) Another apprenticeship sends him south, to guide home the native women recruited to help bolster the dwindling population of Earth. His voyage to the south reveals strange truths about his world, where the ground slips across the planet, gravity intensifies to a suffocating, crushing pull, and the natives shrink and widen into inhuman shapes.

Just what is this planet?

It takes a little bit of brain juice to picture the world that Priest has engineered, and to explain it too much here would spoil the pleasure of discovery for future readers. To sample the flavor, one must consider a blend of the exotic gravity of Clement's Mesklin in Mission of Gravity, the enormous engineering feat of Kim Stanley Robinson's Mercurial city on tracks in 2312, and the supernatural "thinny" from Stephen King's Dark Towerseries. The story of an apprentice learning his trade through a series of heuristic lessons provides an ideal platform for uncovering the mysteries of his strange world to the reader. Priest does a masterful job of teasing and revealing.

In addition to playing with physics, Priest also plays with the tools in his writer's chest. His language is precise and direct, and his characters demonstrate little emotive value, both of which contribute to this world of desperate survival. Within his narrative, Priest uses first and third person perspectives to mimic the effects of this perception-altering gravity, where Helward's first person account is vague, distorted, and frustrating, much like the world he is exploring. Elizabeth, an occasional lead supporting character, is narrated in third-person with more exactness, often acting as the axel on this rickety ride, and as the tale's own optimum.

But Priest's greatest exercise in literary play comes through as genre subversion as the reader learns that not all is exactly what it seems. This can be frustrating for the physics fetishists* if things don't fully make sense in the end, but that's not the point. Inverted World is a direct response to the Hard SF subgenre, specifically to books like Clement's Mission of Gravity, which sacrifice story and art for scientific fact. For this reason, Inverted World can be classified as both mind-bending and genre-bending. Such a satisfying development for this reader.

In addition to mathematical concepts and literary play, Priest also addresses critical social themes. Earth's inhabitants' interact with the surrounding native populations, providing enlightening scenes and subtle critiques of exploitation and ethnocentrism, while illustrating cultural attitudes toward the value of women, labor, and good citizenship. These issues do not drive the plot, but they are always in the periphery, and are just as insidious as the weird grav that perpetuates the edges of their world. Even our good hero Helward (an apt name for a guy who is meant to travel away from his comfortable optimum) is not a hero, not an anti-hero, but something else—a leader who follows, a sheep in shepherd's clothing.

Priest packs a lot in, but the prose is clean, clear, and it never fuddles up the plot. A passive reader can enjoy the narrative without the depth. An active reader can explore the depths without losing track of the plot. In the end, it is a tale about the exhausting, callous, futile things that people will do to survive. It is a cautionary tale against passive acceptance. It is a tale about the importance of questions.

But it is also a tale about the importance of story in a genre that is sometimes crushed by the force of its own scientific gifts.

A must read for any SF fan seeking more than the average read. Inverted World is full of wonder, and it just might bend your mind.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com