![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

11/23/2015

![]()

I'm starting to wonder if Fritz Leiber's early fiction is where it's at in terms of sophistication and daring, while his later fiction is pure career fancy. If so, it's probably an observation longtime readers of SF have already noticed, but of the small assortment of his works I've read, it's becoming a pattern.

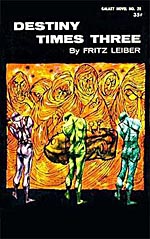

Leiber's 1945 Astounding serial,Destiny Times Three, blends Nordic myth, Persian poetry, and a little bit of Wells into a multiverse story that explores a provocative moral question: What would you do if you found out your multiverse twin exists in a miserable dystopia and they resented you for having the better life?

A sense of guilt toward his dream-twin was the dominant fact in Thorn's inner life. (23)

At first, it is just a "dream-twin", as everyone in Thorn's world is wracked with "nightmares with the same landscape. As if each dreamer were looking through a different window at a consistently distorted version of our own world" (14). But Thorn, a scientist studying the strange shared dream phenomenon, feels pulled towardYggdrasil and stumbles into the "botched worlds" that branch off the main trunk of his world, not-so-incidentally swapping places with his twin from an authoritarian, industrial dystopia:

In three days, he had seen three worlds, and none of them were good. World III, wrecked subtronic power, cold battlefield for a hopeless last stand. World II, warped by paternalistic tyranny, smoldering with hate and boredom. World I, a utopia in appearance, but lacking real stamina or inward worth, not better than the others--only luckier. (110)

Would the real World Order please stand up?

A world where two great nations, absorbing all the rest, carried on an endless bitter war, unable to defeat or be defeated, forever spurred to new efforts by the fear that past sacrifices might have been in vain. A world that was absorbed in the conquest of space, and where the discontented turned their eyes upward toward the new frontier. (116)

1945. Leiber wrote this in 1945.

Not much is written about Destiny Times Three, and it seems like what little I can find focuses on Leiber's character building and science. (Who reads Leiber for his science?!) Yet the majority of this little 100-page story concentrates on tensions between worlds, the humanity that inhabits each, "the Great Man" tinkering that accompanies global political tension, and criticism of the idea of utopia and the dehumanizing superiority toward non-utopia inhabitants:

Everywhere happiness - or, rather, creative freedom. A great rich surging world, unaware, save for nightmare glimpses, of the abyss-edge on which it danced.

Maddeningly unaware. (58)

It's not about the science, it's not about the character building; it's an allegory of political events. What we have here is a sober interpretation (and projection) of events during the tail end of World War II in the European theatre, minus the patriotic lust and dehumanizing zeal that accompanies most science fiction of this era. With Leiber's balanced, critical eye on the diplomatic stage- well, I know we're not supposed to praise SF authors for their foresight, but damned if Leiber seems to side with history on this one.

The utopia that's not really utopian. A multiverse twin trapped in a dystopian regime. A group of men with too much power and the ability to divide the world timeline into branches. An empathic illustration of humanity on the other side. A condemnation of the powerful.

The first thing that struck Thorn--with surprise, he realized--was that the Servants of the People looked in no way malignant, villainous, or evil.

But looking at them a second time, Thorn began to wonder if there was not something worse. A puritanic grimness that knew no humor. A suffocating consciousness of responsibilitity, as if all the troubles of the world rested their shoulders alone. A paternal aloofness, as if everyone else were an irresponsible child. A selflessness swollen to such bounds as to become supreme selfishness. An intolerable sense of personal importance that their beggarly clothes and surroundings only emphasized. (72)

But you chose to play at being gods, and even ignorant and well-intentioned gods must suffer the consequences of their creations. And that shall be your fate. (123)

(The Yalta Conference occurred just the month before this was published.)

It took Jesse from Speculiction to point out to me the subversive commentary of Leiber's Hugo award-winning The Big Time (1958), where the one-room story is situated inside the vacuum of an intangible Cold War-like background. Destiny Times Three is less abstract, more blunt, with paragraphs of prose dedicated to critical commentary. I have no idea if Campbell's Astounding readers in 1945 ever noticed the commentary, or cared, but it's full of red flags:

What's this Martian invasion? Is it real? Or an attempt to rouse your world into a state of preparedness? Or a piece of misdirection designed to confuse the issue and make the Servants' invasion easier? (96)

1945. 1945.

It's stylistically Leiber, with punch and jazz, and an abundance of en dashes-- his brilliance interrupted by more brilliance in every paragraph. Exciting and dynamic, with lots of narrative momentum propelled by morally gray characters (Clawly and Thorn resemble Loki and Thor) and the tantalizing multiverse riddle of the twin. It's a rapid read; devote a Saturday afternoon to this one.

Structurally, it has the stitched-together feel of the serialized format, but there's also the sense that something much bigger could be going on, which a little research confirms that Leiber had epic plans for this story. Unfortunately, due to the pressures of pulp publishing and war rationing, there was no appropriate outlet for Leiber's original 100,000 word intentions and what we get is this truncated Leiberian vision. Somehow Leiber manages to preserve that sense of promise, and there's this lingering sense of a bigger, disembodied story haunting the margins of the pages. The reader can appreciate Leiber's original intention, even if none of it is explicitly written. It's quite a feat for this 100-page book.

The Big Time (1958) stands out for its unique, surreal structure. The Wanderer (1964) is silly fun. (And "Gonna Roll The Bones" (1967) took the long, uncomfortable way of making a shrug-worthy point, and let's not talk about debaucherous Ffhard or whatever his name is.) But Destiny Times Three (1945) seals my fannishness for Fritz Leiber. This is a special book that I highly recommend.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com