![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

5/25/2016

![]()

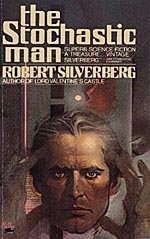

A mathematical and political twist to the predictable telepathy tale, the 1976 Hugo- and Nebula-nominatedThe Stochastic Man at first sight appears to be Robert Silverberg's effort to legitimize one of SF's favorite tropes, though he's certainly not the first to try. Portraying telepathy as random probability forecasting in a political setting explains away many of the fanciful notions that might hinder the believability of yet-another SF work about preknowledge and predestination, but, considering earlier SF writers explored the same ideas with similar conceit of logic, once dubbing the method Null-A, psychohistory, and, as Max Cairnduff cleverly reminds us in his review, is now called consulting, the attempt to blend superpowers with real-world applications is neither new nor fresh. What makes The Stochastic Man different from its pseudoscience ilk, aside from that gritty '70s essence, is that Silverberg draws from far older inspirations, adding a decidedly Faustian framework to this tale.

In brash, first-person style, Lew Nichols recounts his days as a budding and ambitious stochastician (trends analyst) vetted to aid the campaign of an equally budding and ambitious, and overwhelmingly charismatic politician, Paul Quinn. While Nichols' stochastic inner-eye sees vague probabilities of Quinn's rapid rise to the presidency, he never quite achieves the clarity of real predictive sight until he meets the aging and mysterious Martin Carvajal, who promises him the gift of prophecy, in exchange for control over all of his decisions, or, as Carvajal calls it, a surrender to the destiny that he knows will occur. Nichols' vacillating assent comes at a price: his rickety marriage collapses, he loses his job, and his own faith in causality is rocked to the core. But were these things inevitable anyway?

Do you believe in simultaneity? I do. There's no stochasticity without simultaneity, no sanity either. If we try to see the universe as an aggregation of unrelated happenings, a sparkling pointillist canvas of noncausality, we're lost.

Carvajal, whom Nichols describes as "dark and tortured," presents an "improbable access of strength" with "eyes, bleak and lifeless, still betrayed some vital absence within." To be alone with him "was suddenly overwhelmingly disturbing" to which he "perceived something terrifying and indeterminable, something powerful and incomprehensible". "That ghostly smile, those burned-out eyes, these cryptic notations." Clearly, you see, Carvajal is the Devil, and he's got a deal to offer.

But this is an SFnal deal with the Devil... a '70s SFnal deal with the Devil... a Silverbergian '70s SFnal deal with the Devil, that is to say there is a twist. Nichols' wife, Sundara, is the non-Christian, non-innocent foil to Faust's Gretchen- and the random detail in Nichol's safe and predictive life. They share an open sex life, with which Nichols, at most times, suppresses his discomfort, making his insecurity amid all that brashness all the more noticeable. At one point, Sundara obtains a prostitution license in order to "subordinate the demands of [her] ego to the needs of those who come to [her]." It's clear to all but Nichols that the marriage is deteriorating long before Carvahal's influence, and long before he finds his wife nude and on the floor with another woman in a ritualistic fervor, "the dark nipples and the pink," as Nichols puts it.

And that's where many readers will object, and should, and it can't be explained away. The sex is fine, the T&A is fine- it fits their lifestyle and the narrative, portrayed as sexy rather thanleery- but the objections arise when Sundara's ethnicity is eroticized in all of her scenes, shrinking the obviously complex Sundara to nothing more than a Kama Sutra diagram. Granted, Lew Nichols' first-person POV is to be blamed for simple and misleading impressions of others, but Sundara gets 2-D treatment when even the cryptic Carvajal or charismatic Quinn display more realism, making her depiction most likely a cheap effort to incorporate exotic sex into the story. Moreover, the unreliable POV can't be completely blamed considering the story is told in flashback form, from a lonely moment in Nichols' future: post-divorce, pre-vision-inspired-reunification, when Nichols should be missing his ex-wife. But to do that would deepen Sundara's character and perhaps take the fun out of all her naked, Kama Sutra glory.

Sundara's promiscuity isn't the only deal-with-the-Devil twist. The story subverts expectations with its conclusion: by knowing and ultimately accepting his own inactive bystander role in the death of Carvajal, Nichols completes his metamorphosis as a believer in predestination, thereby incorporating Carvajal's role as his own, the soul transfer in reverse. Rather than lose his soul to Satan, he absorbs the soul of Satan:

The real script called for me to do nothing. I knew that I did nothing...

I ran to him and held him and saw his eyes glaze, and it seemed to me he laughed right at the end, a small soft chuckle, but that may be scriptwriting of my own, a little neat stage direction. So, So. Done at last... The scene so long rehearsed, now finally played. (ch. 43).

Carvajal died on April 22, 2000. I write this in early December, with the true beginning of the twenty-first century and the start of the new millennium just a few weeks away... We have been here since August, when Carvajal's will cleared probate with me as his sole heir to his millions.

...What we're doing is a species of witchcraft... (44)

"Sole heir," he says.

Interestingly, Nichols explains this witchcraft as an effort to counteract the imminent rise of his one-time employer, now turned foe, the awe-inspiring and charismatic Paul Quinn, which Nichols' Carvajal-influenced visions eventually view as "the coming führer," a threat to democracy and free speech, though with zero evidence (beyond an empty, yet inspirational, utopia speech) that this will ever be the case. It's never clear by book's end whether Nichols is responding to a real threat, or just paranoiac hallucinations inspired by his termination- or a devil-inspired concoction of deceptive visions.

Speaking of paranoiac, so much of the political, metropolitan atmosphere brings to mind a New York City estranged from modern collective consciousness. Without enough exposure to old Saturday Night Live! episodes, it's easy for my generation to go on unawares of pre-Hershey's Chocolate World Manhattan. Most recently for me, both this novel and Katherine MacLean's Missing Man (1975) have not only reintroduced me to the mythical seediness of a pre-Giuliani'd Big Apple, but both books also portray the alarmist White fears of non-White danger that spurred mid- to late-20th urban White flight (which has somehow circled back around to urban White gentrification- the double-whammy post-post-imperialist urge, I suppose). Between MacLean's race-based burrough Kingdoms and Silverberg's race-based commando gangs, the real truth lies in the authorial psychology of these surface depictions: privileged reticence to acknowledge the roots of social problems, fueled by sensationalized fear and disguised as witty cynicism.

In this city we invent new ethnic hostilities. New York is nothing if it isn't avant-garde.

Race riots are the new Dadaism, y'all. If only it were that simple.

Structurally, The Stochastic Man is a story written in 1975, told in 2000, about the previous thirty-five years, heavy on the speculative nineties, and flashes of post-2000 moments, having more in common structurally with the time-travel subgenre than its own telepathic peers. But that's what keeps the story interesting. The tension between will and destiny drives these types of tales, and to begin at the ending and work your way back adds its own bit of mystery. (Proof that spoilers can actually make a tale more successful because wondering how it gets there is more surprising than finding out who died.) Most interesting, however, is that The Stochastic Man, in all its prophetic posturing, can tell us everything that happened, but without that sense of causality, as Lew Nichols says, "we're lost."

As dynamic as it is flawed, Silverberg's work straddles the line between rude and galvanizing-my kind of fiction- though he doesn't take care to avoid the more problematic elements. What's just as bothersome about Silverberg's success, or perhaps moreso, is what I like to call Johnny Depp Syndrome, in which he was inexplicably in everything,dominating attention by appearing on SF awards lists and in anthologies for most of a decade, calling into question, perhaps unfairly, the worth of his work over what might instead be accounted for by a formidable blend of commercial status and unadulterated fan-feeding male charisma. My own generational distance buffers that lack of credulousness just enough to take his work seriously while also wondering what other dynamic and rude and galvanizing 1970's authors might be buried by those nine Hugo Best Novel nominations, among a myriad of other honors.

Which brings me back to 2016, where my own stochastic sight foresees a summer of at least a couple of Johnny Depp Syndromeblockbuster novels, probably more, and while I side-eye their Big Media Squee Reviews, I will likely read them all, apply my free-time thinking thoughts to them, and maybe even give them a pass, all while wondering to which devil do I have to sell my soul to see something different.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com