![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

9/11/2016

![]()

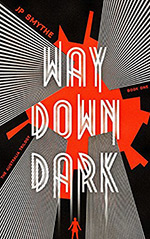

If The Long Way represents the Tyranny of the Big, Happy Dysfunctional Family, then Way Down Dark represents the Tyranny of the Individual, the lizard-brained us-versus-them mentality that also infects a lot of genre work. Billed as Young Adult fiction, appropriate because of its sparseness, it does not belong on a non-dedicated YA shortlist; a mixed list like this is unfair to both sides of the divide that draw from different skills sets and techniques. Stop this nonsense and create more YA-dedicated SF awards lists.

Taking place on a generation starship with an Inferno-like vertical quality, the young protagonist scoots and climbs and hops around the decaying vessel making it more like a kind of Chutes and Ladders: In Space. But Chan steals the show anyway, because she is a total shaved-head badass, leaping off railings, fighting crazies, and saving kiddies. Her adventures, though nonsensical most of the time, are riveting. Smythe knows how to hook: the story opens with Chan violently euthanizing her mother, she murders (or not?) a man for a pair of shoes, and her persistent enemy, the mindlessly violent "Lows," attack from every nook and stairwell. Never mind that the bottom of the ship is a noxious lake of human effluvia that Chan must swim in, in order to reach Sanctuary.

Rip-roaring space adventure for kids, it is. Gruesome? Brilliant. Hyper-violent? Sign me up. Baby saving? I'll read that shit. Oh, but now here come the "why's?"

Violent, barbaric, and just as vertically symbolic, J.G. Ballard's High Rise (1975) traces the devolution of residents in a tower block as they retreat inward to their concrete world and away from their humanity. A harrowing account of a community's descent into isolation, individualism, and inhumanity, and how the structures of our world are fostering this descent, it is a brilliant masterpiece that ends just before the submission to complete animalism. Way Down Dark begins after that point. All we know is that the "Lows" are tribal, territorial, violent, and destructive. They kill for pleasure. They terrorize for fun. The normal citizens are the minority, picked off one-by-one, or absorbed into the clan. It makes for great high-stakes drama, but only if you don't think about it too much because the philosophical magic of High Rise is missing: Why? Why are the Lows so inhuman? Have they evolved to a point beyond the animal instincts of propagation and cooperation? Are they just so bored? Haven't we learned from our own human history that cooperation is so crucial and instinctual as to make a survivalist story like this dubious without a proper explanation for why the tendency for human cooperation has been undermined in this setting?

The clincher may be in the SPOILER: This generation starship, called The Australia, is actually a prison colony suspended outside Earth's (assuming) atmosphere. On the Cabbages & Kings podcast, Maureen K. Speller goes into a very interesting account about how this ties into the Australia-that-we-know's own heritage of being the home of British-expelled convicts. For that reason, we might be able to retroactively view this as a critique of prison systems and the institutionalized cruelty they nurture, but that doesn't save the novel from reinforcing the idea of heroic exceptionalism, with Chan and her few friends being somehow immune to the call of the Lows, instead desiring safety, structure, spaghetti, and a good washing up. Although Chan experiences a few moments of morally ambiguous decisions, she's never in any danger of becoming "one of them." What makes her so fucking special?

So, this could have been a critique of prison systems. More interestingly, it could have been an inside look at the "Lows," their power structure, their system, and their history. Way Down Dark is successful as pure entertainment, but, even as a YA novel, it could do these other things, too. So why didn't it?

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com