![]() Sable Aradia

Sable Aradia

1/10/2017

![]()

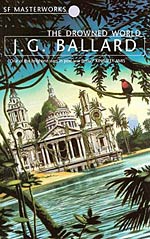

Read for the Apocalypse Now! Reading Challenge and the SF Masterworks Reading Challenge.

Method of the world's destruction: fluctuations in solar radiation melt the polar ice caps, causing massive flooding in most of the world's major cities, rising heat, and heavy rains that make the equatorial belt uninhabitable.

This was definitely not my favourite of the SF Masterworks collection. It's my first acquaintance with the writing of J.G. Ballard, aside from his autobiographical Empire of the Sun, which made an enormous impression on me as a child when I saw the Spielberg movie. I never forgot the thousand-yard stare so accurately portrayed by the boy who played young J.G. after his ordeal as a British prisoner of war in WWII Japan. It was said in the introduction to the edition of this book that I read that Ballard was perhaps somewhat damaged in his ability to portray human feelings and relationships as a result of his experience. Perhaps that's true, because the characters seemed stilted and weird, and their motivations did not make sense to me.

How it was explained was thus: the Drowned World resembles the ancient world of the Triassic period of Earth's history. Lurking in our cells is the instinctive memory of our ancient ancestors, nestled in our lizard brain (the brain stem). That cellular memory is being activated by the strong resemblance of this new world to the ancient one, and some people (maybe all people) are being drawn into those memories and acting instinctively in ways that would be more consistent with the ancient lizards that became the first mammals, that became us.

Subsequently, the protagonists spend most of the novel trying to stay behind in drowned London while the military expedition that is mapping the remains of the coastlines in a geographical survey leave it. (And, for some reason, some wealthy woman named Beatrice is still here in the abandoned lagoon of London, whose only purpose in the novel was to save the main character's life by intervening on his behalf at one point.) They sabotage the base, abandon useful survival items, and sit around in a dazed, overheated, psychotic torpor through most of the book, all of which is distinctly against their own self-interest and survival.

I found this a mystery at first, because I would have thought that regressing to more instinctive behaviour would make one more likely to fight to survive, and to flee the dangers of the drowning world (including giant alligators and iguanas that eat you) as soon as possible. Then my partner suggested that the lizard brain is less likely to reason cause and effect, and simply reacts to the moment. That made it make a bit more sense, but even so, I found a lot of behaviour inconsistent. Near the end of the book, the main character launches a complex plan and takes a gun with him. It's strange. Other inconsistencies include lighting a fire somehow with waterlogged wood that has been underwater for literally years, but somehow it manages to dry out even in humidity that rivals Niagara Falls (but perhaps they used gasoline).

Society has retreated to the poles; though I'm not sure what they're living on, since this story takes place in London, which isn't exactly in the lower latitudes, and the ice caps have mostly melted, so I doubt there's much land up there. But the characters seem to have an instinctive drive to head south, called by the thrumming of a sun that is both modern and ancient. Neither of these things are ever explained. Is there some kind of ancient migratory instinct being activated? Did the sun in Ballard's world used to make noises as it spun, like a pulsar? We don't know; he doesn't tell us. I suppose there's always room for mystery but I personally find this frustrating.

I can see why the book has been reprinted, however. Sometimes science fiction is about ideas, not plotlines, and the truth is, if we don't get our collective sh*t together, this is what our world is likely to look like. It's already started; ice shelf retreating at an unprecedented rate,the global temperature rising 1.4 degrees F since 1880, the past two decades being the hottest in 400 years and possibly millennia. Greenhouses gasses will do it just as quickly as solar radiation; just ask Venus.

The introduction presented the idea that one might enjoy the book more if one viewed the developing world as a character, perhaps with sinister intent. That does tend to improve the read, or so I found. But I'm the kind of reader that wants a story about people. I think if it's about ideas, this could have been accomplished in a 7500 word short story.

Perhaps the novel is best considered as a rebuttal to the "noble savage" tales of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Kipling. As an English boy, I'm sure Ballard grew up on these stories, which postulated that if a man were to ditch all the trappings and nonsense of civilization, they would become more brave and noble than any "civilized" man could be. And then Ballard experienced being a prisoner of war. One of the characters, a guy named Strangman (probably a clue) was the only white man, leading a ship full of savage black crewmen who talked like caricatures from the Caribbean (shades of the racist British Imperialist Tarzan themes,) and they were nasty just for the sake of being nasty. And the law supported their nastiness. To my mind, it's like Ballard was saying, "Yeah? You want to know what Man looks like freed of civilization? This is what he looks like!" Up to and including the supposed "civilizing effect" of Woman, who appeals to Man's better nature like a magic talisman that makes him kind of behave himself.

But in either case, I personally found this book somewhat of a tedious slog until more than two thirds of the way through it. When I read, I'm looking for a good story. I respect the ideas presented here, and I see why The Drowned World made the SF Masterworks list - it might be the first ever cli-fi story. But it wasn't my cup of tea.

http://dianemorrison.wordpress.com