Outside the Norm: Ursula K. Le Guin’s Planet of Exile

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

My last blog about Margaret Atwood and science fiction inadvertently led me back to Ursula K. Le Guin, who has been an important commentator on Atwood’s work. (See the comments to that blog to find some interesting links to Le Guin about Atwood and Atwood about Atwood.)

My last blog about Margaret Atwood and science fiction inadvertently led me back to Ursula K. Le Guin, who has been an important commentator on Atwood’s work. (See the comments to that blog to find some interesting links to Le Guin about Atwood and Atwood about Atwood.)

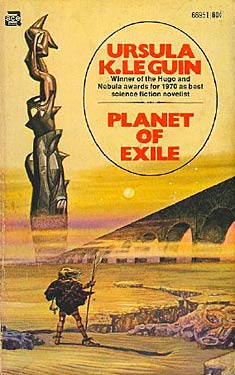

An omnibus edition of Le Guin’s works called Three Hainish Novels has been moving in and out of my to-be-read stack for more years than I’d like to admit. This edition contains the first three Hainish novels, Rocannon’s World (1966), Planet of Exile (1966), and City of Illusions (1967). I don’t know why I’ve not read these novels yet. My favorite book is The Left Hand of Darkness. (I know this because a colleague recently made me choose one book for a list he was putting together. It was very hard to choose, so I decided to pick the book that I had re-read more than any other. That was The Left Hand of Darkness.) When I read it in the late 80s, The Left Hand of Darkness changed the way that I thought about gender, writing, and science fiction. It even spurred me to do a research paper in a linguistics class about pronouns and gender. So, now, almost thirty years later, it’s time to finish the Hainish Cycle, beginning with these three novels. This blog will discuss the middle novel, Planet of Exile.

I like Soft SF, and I like world-building novels. And, lucky for me, so does Le Guin. She writes in her essay "Do-It-Yourself Cosmology":

As soon as you, the writer, have said, "The green sun had already set, but the red one was hanging like a bloated salami above the mountains," you had better have a pretty fair idea in your head concerning the type and size of green suns and red suns—especially green ones, which are not the commonest sort—and the arguments concerning the existence of planets in a binary system, and the probable effects of a double primary on orbit, tides, season, and biological rhythms; and then of course the mass of your planet and the nature of its atmosphere will tell you a good deal about the height and shape of those mountains, and so on, and on…. None of this background work may actually get into the story. But if you are ignorant of these multiple implications of your pretty red and green suns, you’ll make ugly errors, which every fourteen-year-old reading your story will wince at; and if you’re bored by the labor of figuring them out then surely you shouldn’t be writing science fiction. (The Language of the Night, 122)

This kind of specificity and willingness to play with the implications of physical systems allow Le Guin to create intriguing societies that relate to the attributes of the planet. For example, the properties of Werel, featured in Planet of Exile, will create very resilient cultures that are governed by seasonal rhythms:

The green third planet took sixty of Earth’s year’s to complete it year…. The winters of the northern hemisphere, tilted by the angle of the ecliptic away from the sun, were cold, dark, terrible: the vast summers, half a lifetime long, were measurelessly opulent. Giant tides of the planet’s deep seas obeyed a giant moon that took four hundred days to wax and wane. (City of Illusions 307)

Planet of Exile opens as this long, bitter winter comes, and one of the indigenous populations, the Tevarans, begins building its Winter City, a place where this agrarian culture will hunker down to outlast the raging winter and the raids of the nomadic culture, the Gaals, who always move south in winter. This hibernation of approximately fifteen Earth years is something the culture dreads and works to provide for throughout the rest of the long Werel year.

The fertility of the Tevarans is governed by the rhythm of the seasons. One is either Autumn-born or Spring-born. Rolery, a child born in the Summer, is out of sync with her people. Her Father, Wold, considers her place in this polygamous culture:

She looked to be about twenty moonphases old, which meant she was the one born out of season, right in the middle of the Summer Fallow when children were not born. The sons of Spring would by now be twice or three times her age, married, remarried, prolific; the Fall-born were all children yet. But some Spring-born fellow would take her for third or fourth wife; there was no need for her to complain. (Planet of Exile 150)

However, Rolery explains her situation differently:

[W]hen Winter’s over I’ll be too old to bear a Spring child. I’ll never have a son. Some old man will take me for a fifth wife one of these days, but the Winter Fallow has begun, and come Spring I’ll be old…. So I will die barren. It’s better for a woman not to be born at all than to be born out of season as I was. (Planet of Exile 150)

Rolery’s situation makes her an outsider in her own culture. She does not have an age cohort. Her loneliness fuels her curiosity about the other cultures that inhabit the planet. The book opens with Rolery brazenly entering the city of the farborns, the Alterran colonists who arrived six hundred years earlier and had lost contact with their empire, the League of All Worlds. Rolery wants to see the sea, so she travels through the Alterran city. She is almost caught by the fast moving tide, but is saved when the Alterran, Jakob Agat "bespeaks" her—he sends her a telepathic message to run.

This encounter begins a relationship between Rolery and Jakob. Her situation as a Summer-born allows her to pursue this semi-taboo relationship. (Her father once had a farborn wife, but, of course, Wold is the tribe leader and a man.) Sexual relationships between Alterrans and the planet’s indigenous populations are sterile, but Rolery knows that she is doomed to barren relationships. Therefore, she chooses to become the first wife in a monogamous marriage rather than a later wife in a polygamous marriage.

This encounter begins a relationship between Rolery and Jakob. Her situation as a Summer-born allows her to pursue this semi-taboo relationship. (Her father once had a farborn wife, but, of course, Wold is the tribe leader and a man.) Sexual relationships between Alterrans and the planet’s indigenous populations are sterile, but Rolery knows that she is doomed to barren relationships. Therefore, she chooses to become the first wife in a monogamous marriage rather than a later wife in a polygamous marriage.

This "star-crossed lovers" plot is only a sub-plot in the novel. The real marriage happens between the Alterrans and the Tevarans, who must learn to rely on one another. Those pesky Gaals, who in the past had briefly harried the Winter Cities and the Alterran city as each nomadic group journeyed southward, have organized. Under the leadership of a Gaal Ghengis Khan, these hordes are moving southward as a conquering machine, burning cities, and stealing livestock and provisions. They leave death and destruction behind. Alterran scouts report this to Jakob, who must convince Wold and the Tevarans of the danger. His relationship with Rolery damages his credibility, and as a result of the Tevaran’s inaction their Winter City is destroyed by the Gaal. Alterran guerillas are able to save many of the Tevarans and bring them into their city. The long siege begins, and the Alterrans and the Tevarans have to learn how to live together.

The book is a fun and quick read. The romance is not overdone, and the cultures that Le Guin creates are developed and are not simply opposites of each other. Each culture demonstrates some interesting nuances that fit their unique situations. I think this novel is my favorite of the three. More on the other two in my next blog.

Full Details

Full Details

5 Comments

I never thought of Ursula K. LeGuin as outside of the norm. She is certainly one of the most revered and honored authors in Scince fiction today.

My introduction says that I want to read more women, persons of color, or non-US, non-UK writers this year. I understand that UKL is more mainstream than most in the category of "female science fiction writer." When I decided to read these three books for a couple of my reading challenges, I thought why not write a blog about them. Don’t worry; there are more writers who are further "outside" coming later.

How about taling a look at Suzy McKee Charnas. Walk to The End of the World is a great piece of work that should be widely read.

I actually don’t mind the label "outside the norm" for Le Guin. At a time when science fiction was so often dismissed by the literary mainstream as inconsequential genre fiction (and often still is), she remained very loyal to the science fiction community and wrote a canon of work that are all just exemplary. She always astonishes me in her attempts to create worlds with distinct cultures and people and mythologies, and her understanding of cultural anthropology, Jungian psychology/mythology, Taoism and feminism is beyond reproach. There is not a single book/story that I dislike. I find her "Always Coming Home" one of my absolute favourites – a fictional ethnography of a people long since disappeared. If nothing else then this book alone sets her "outside the norm." She lovingly created a rich culture of the Kesh with intricate detail such as their songs, children games, poetry and excerpts from novels, histories, death rituals and the like. It was a wonderful Utopia where men and women just are. Thanks so much for spending time on Le Guin, my all time favourite author.

@Thomas. Thanks. I’m adding her to my list now.@Emil. What you describe is what made me come back and back to The Left Hand of Darkness. Every time I reread a myth, I saw newer and different connections to the main narrative. I have a feeling that I’m going to be reading a lot of Le Guin this year.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.