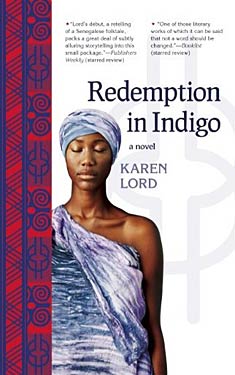

Outside the Norm: Karen Lord’s Redemption in Indigo

Rhonda Knight is an Associate Professor of English at Coker College in Hartsville, SC. She teaches Medieval and Renaissance literature as well as composition courses. When she looked over last year’s reading list, she was shocked to see that only 17% of the authors she read were women. This blog will record her attempts to read authors that are generally considered out of the science fiction norm: women, persons of color, and non-U.S. and non-U.K. authors.

Nalo Hopkinson calls Karen Lord‘s Redemption in Indigo "[t]he impish love child of Tutuola and Garcia Marquez." I have never read Tutuola, but I immediately understood Hopkinson’s comment when I started reading the book and thought it was a mixture of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. So, no matter what authors or book the readers use for their analogies, the most compelling feature of Redemption in Indigo is its ability to mix New World magical realism with Old African folktales, in her case the world of Barbados and its undying spirits, the djombi, with the Senegalese folktales of Anansi, the spider trickster god.

Nalo Hopkinson calls Karen Lord‘s Redemption in Indigo "[t]he impish love child of Tutuola and Garcia Marquez." I have never read Tutuola, but I immediately understood Hopkinson’s comment when I started reading the book and thought it was a mixture of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. So, no matter what authors or book the readers use for their analogies, the most compelling feature of Redemption in Indigo is its ability to mix New World magical realism with Old African folktales, in her case the world of Barbados and its undying spirits, the djombi, with the Senegalese folktales of Anansi, the spider trickster god.

The book begins by setting up the narrative as a tale told by a storyteller: an "I" who is talking to a group of "yous," of which the reader is one. The story playfully ends with the storyteller’s solicitations:

"it is terribly dry and thirsty work, speaking these lives into the dusty air of the court, speaking for you to hear and ponder and judge. Perhaps, if you would be so kind as to contribute, I could purchase some refreshments now, find a place to rest my head later, and return to you on the morrow with my voice and memory and strength restored. Please, ladies and gentlemen, if you have at all enjoyed my story, be generous as the pot goes around, and do come back again soon." (182)

He similarly begins the epilogue by telling us that he has been "authorised" to tell us more. This narrative method enhances the folktale elements because it provides an inventive way to fill in cultural background for readers who probably aren’t familiar with the ways of the greater and lesser djombi and the other supernatural beings they encounter.

Our storyteller begins with the story of Paama, who’s left her husband, Ansige, and returned with her family to her village. Paama leaves her husband because of his gluttony. He was "not an epicure, but a gourmand," his every thought and action controlled by his desire for food and his only worry about his next meal (7). When Ansige finally arrives at the village to beg her to return to him, his exploits demonstrate his origin in East African folktale characters. His gluttony gets him into all kinds of trouble from which Paama has to rescue him. However, Paama has bigger problems than her husband. Before Ansige even arrives at her village, two djombi have decided to steal Chaos from another djombi and give it to Paama, which will give her immense power. Just as Paama starts to understand her unwanted power, the indigo djombi, the original wielder of Chaos, has tracked his power to her village.

The relationships Lord forges between the supernatural beings and humanity elevate the plot beyond the typical tale of a heroine who must fight to save her people and their way of life. The supernatural beings are complex characters who are dissatisfied with the way their identities often limit their roles. The storyteller speaks about the indigo djombi:

The djombi are like the human creatures they meddle with, apt either to great evil or great good, and sometimes they switch sides.

This one was the unknown danger. He had switched sides. He had started with benevolence, with the belief that there is the fine potential in humankind waiting only to be tapped. He now viewed the whole stinking breed as a pest and a plague. (58)

As a symbol of his change from benevolent to malignant, the djombi changes his color to indigo, "a stark and utter setting apart that provoked as much of horror as of awe" (59). Another supernatural being, the Trickster, who usually appears in the form of a spider, changes in the opposite direction. He began "delighting in the frailties of humans and exploiting those weaknesses for his own entertainment" but became bored with "playing the same old practical jokes" (102). After a while he started "turning people to situations of mutual benefit rather than merely gratifying his own sense of the ridiculous" (102). The pleasure in this novel is observing these beings as they learn about their omnipotence and start to interact with Paama and her community in a meaningful way. The ending, while somewhat predictable, gives the readers the happy endings and the redemptions that the title tells them to expect.

As a symbol of his change from benevolent to malignant, the djombi changes his color to indigo, "a stark and utter setting apart that provoked as much of horror as of awe" (59). Another supernatural being, the Trickster, who usually appears in the form of a spider, changes in the opposite direction. He began "delighting in the frailties of humans and exploiting those weaknesses for his own entertainment" but became bored with "playing the same old practical jokes" (102). After a while he started "turning people to situations of mutual benefit rather than merely gratifying his own sense of the ridiculous" (102). The pleasure in this novel is observing these beings as they learn about their omnipotence and start to interact with Paama and her community in a meaningful way. The ending, while somewhat predictable, gives the readers the happy endings and the redemptions that the title tells them to expect.

Because Karen Lord explores these big ideas of omnipotence and redemption in a Caribbean setting, her book has garnered attention outside the F/SF community. It won the 2008 Frank Collymore Award, given to an unpublished Barbadian work. It was also nominated for the 2011 Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature. Back in the F/SF world, the book was a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and won the 2011 Mythopoetic Award and the 2011 Crawford Award for the best fantasy novel by a new writer. For more on its awards, see Karen Lord’s interview with Chesya Burke.

The adjective that comes to mind when I think about Redemption in Indigo is fresh. The story has recognizable elements–heroes, gods meddling with the affairs with humans, mythological characters and folktales–but Lord uses these elements in unexpected ways, except for the ending, which is satisfying in its predictability. Her style of fantasy is smart, inventive, and innovative. I look forward to Lord’s next book.

Full Details

Full Details

5 Comments

I liked this book, but are you sure it is set in Barbados? I started out thinking so, but the description of places, names of people, and foods seemed far more Senagalese, and not just because the tale comes from there. I do hope to see more from this author.I also wanted to say that I’d you liked this and are trying to read more women, I think you’d love Who Fears Death by Nnedi Okorafor.

If I remember right, I don’t think the setting was ever really defined, but I also got the sense it was reminiscent of West Africa. This is one of my favorite books from the last few years, so I’m glad to see it get more attention! One of the best aspects is the humor. I thought it also dealt interestingly with the way Paama managed to assert her independence and power, while trying to continue to respect her society’s (patriarchal) traditions. Looking forward to more in this series of reviews…

Rhonda Knight, you beat me to this one. I started it a couple of nights ago and immediately thought it might deserve special attention. I haven’t yet read your post, but I look forward to it once I finish the book in the next day or so.

@Jenny, point well taken. The setting is certainly a kind of no-specific place, no-specific time world (and I didn’t do a good enough job explaining that above.). The reason that I thought that the setting was New World rather than Old World is the way that the West African myths had that feel that they’d traveled the Middle Passage and had been reinterpreted for a different location. However, maybe I was basing much of that on the use of djombi.I have not read Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death yet. However, I did review her The Shadow Speaker and Zahrah the Windseeker for this blog series. Who Fears Death and Akata Witch are firmly on my to be read list.

@Scott and Charles Dee (no spoilers)I was really excited by this book. It opens up all sort of possibilities for world settings and pantheons in F and SF.As a commercial, one of my next blogs will be about Dubravka Ugresic’s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg. She’s a Croatian writer who won the Tiptree Award in 2011.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.