![]() thrak

thrak

10/21/2014

![]()

"Belief and science aren't mutually exclusive - quite the contrary. But if you place scientific standards first, and exclude belief, admit nothing that's not proven, then what you have is a series of empty gestures. For me, biology is an act of religion, because I know that all creatures are God's - each new planet, with all its manifestations, is an affirmation of God's power."

"Almost all knowledge, after all, fell into that category. It was either perfectly simple once you understood it, or else it fell apart into fiction. As a Jesuit - even here, fifty light-years from Rome - Ruiz-Sanchez knew something about knowledge that Lucien le Comte des Bois-d'Averoigne had forgotten, and that Cleaver would never learn: that all knowledge goes through both stages, the annunciation out of noise into fact, and the disintegration back into noise again. The process involved was the making of increasingly finer distinctions. The outcome was an endless series of theoretical catastrophes.

"The residuum was faith."

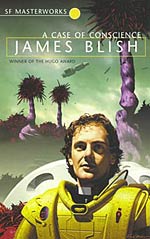

'A Case Of Conscience' is a truly unsettling work of fiction. It is a nuanced exploration of the often fraught relationship between science and religion, focusing in particularly on the theological question of if there are other forms of sentient life out there, did Jesus die for their sins also? This is a genuine issue that has been debated by theologians of different backgrounds. The question forms the basis of C. S. Lewis' Space Trilogy, ultimately a much less intense work than Blish's. The aliens on Lewis' Mars and Venus have no Original Sin, and so never fell from their state of grace; Earth is the only planet where Jesus had to be sent because the Fall of Man only happened to us. 'A Case Of Conscience' is much less comfortable. Ramon Ruiz-Sanchez, the Jesuit priest and biologist sent to the planet of Lithia to determine its suitability for humanity, decides that because the Lithians live a perfectly moral Christian life without any need for God, the whole planet must be a trap designed by Satan to dissuade people from believing in God. What follows is one of the most potent dissections of Catholicism outside of Graham Greene's 'The Heart Of The Matter', Like Greene's novel, 'A Case Of Conscience' explores how a person with courage and integrity can wind up making a horrific choice that, from the point of view of his own convictions, is the moral choice.

A lot of this works as well as it does because of how closely Blish plays his narrative cards, and how well Blish develops Ruiz-Sanchez as a character. The entire edifice of the book would come crumbling down around itself were Blish to make the nature of Lithia explicitly demonic, but equally Ruiz-Sanchez's struggle would be meaningless if he were simply an easily-manipulated or self-deluded buffoon. Ruiz-Sanchez is instantly likable, clearly a dedicated and perceptive biologist who's faith enhances rather than detracts from his interest in science. Out of the humans who have visited Lithia, Ruiz-Sanchez is the only one who can speak their language anything close to fluently and the only one who has friends among the Lithians. The first half of 'A Case Of Conscience' focuses on Ruiz-Sanchez and the three other humans who have been sent to assess Lithia, mostly as they discuss their reasons for and against opening the planet up to humanity. Before we hear Ruiz-Sanchez's argument, we hear the arguments of his colleagues. Cleaver, a materialist and physicist, argues that Lithia should be cordoned off from the rest of humanity, so that he and the other free can turn the planet's vast natural resources into a munitions factory and make a fortune by using cheap local labour. Michelis, a humanist, points out just how unethical and paranoid Cleaver's intentions are, and points out how much humanity could learn from the peaceful and prosperous Lithian society. Naturally, from what they know about Ruiz-Sanchez's character, and from his own repeated assertion that his decision about Lithia will be based on conscience rather than reason, Michelis and Cleaver, and indeed the reader,expect him to side with Michelis. So it is genuinely shocking when Ruiz-Sanchez declares that Lithia be isolated from all human contact forever.

Ruiz-Sanchez's argument is an interesting one, not least because it damns him in the eyes of his own church. By acknowledging that the devil could have created the Lithians, he is committing heresy, because the doctrine of the church states that only God can create things. Very often in science fiction we come across alien cultures that share morals similar to our own, and it very rarely commented on how incredibly unlikely this is. Ruiz-Sanchez points out that for the Lithians to live entirely by an arbitrary code of conduct that just so happens to completely match Christian ethics, which they do, simply because they find it works for them, is an incredibly unlikely thing to come about by chance. Because the Lithians are able to live this life as paragons of good Christians in their perfect society, far more so than any human struggling to live their life by Christian tenets ever achieves, demonstrates that it is possible to live a good, Christian life without the existence of the spiritual side of Christianity, that is, without God. This is reflected in the biology of the Lithians, who, as bipedal reptiles with young that have aquatic and amphibious lifecycle stages, undergo recapitulation of evolution outside the womb. Everything about the Lithians supports the theory that intelligent life can develop, thrive and live a full moral existence without the interference of God at any stage in the process. The planet's very ecosystem, comprising of lush Jurassic forests, even resembles an image of Eden before the Fall. Ruiz-Sanchez can only assume that the entire thing is a trap to draw people away from God and towards damnation, and hence he feels responsible for any souls lost as a result of contact with it.

Whatever one's spiritual beliefs or lack thereof, there is something terrifying about a devil that subtle. And of course in reality evil is capable of subtlety, as Ruiz-Sanchez himself points out. But the idea that the very existence of an entire planet could be an intellectual trap is deeply disturbing. It is also incredibly solipsistic and arrogant, and is an interpretation that completely robs the Lithians themselves of any kind of agency. 'A Case Of Conscience' also doubles as a critique of colonialism. Ruiz-Sanchez sees the Lithians in terms of how similar their society conforms to his idea of a good society as both a Jesuit and a product of however many years of Western civilisation. However this blinkers him from seeing them as their own people, and ultimately from seeing them as anything but a threat to his own ingrained system of belief. So Ruiz-Sanchez is entirely capable of having pleasant conversations with Chtexa in Chtexa's own language and expressing genuine interest in the Lithian's own culture whilst in his mind labeling him as a product of the mind of Satan, only existing to drag him into temptation. It is this attitude that leads him to side with Cleaver over Michelis, which instead of letting the cooped up, frustrated and paranoid Shelter society on Earth learn from cultural exchange with the Lithians allows Cleaver to exploit the Lithians behind the UN's back, and ultimately to the book's tragic conclusion, all whilst believing he is doing right by his conscience.

Chtexa gives Ruiz-Sanchez a flask with one of his young in it in the spirit of cultural exchange, and the second half of the book focuses on Ruiz-Sanchez and Michelis's attempts to raise Egtverchi, Chtexa's son, on Earth, Egtverchi becomes a celebrity with is own TV show, where he incites chaos amongst the Shelter society's disillusioned millions. Egtverchi's mantle of dark messiah feeds into Ruiz-Sanchez's and the church's view of the Lithians as demonic in origin, and the rioting he unleashes threatens to turn into a full-scale apocalypse, spelling out the end of the Shelter society that has allowed Earth to survive in the shadow of potential nuclear annihilation since the end of the cold war. However Egtverchi doesn't stir anything up that isn't already there; like Shevek in Ursula Le Guin's 'The Dispossessed', his presence as an envoy from a different way of life means that he acts as a catalyst to all those disillusioned and suffering under a deeply unfair and unstable system. The' Shelter system has built up by essentially forcing people to live underground in structures that were built to survive the nuclear apocalypse, and the cramped and paranoid living conditions has bred generations of people with undiagnosed and untreated psychological conditions. There's also a subtle undercurrent here of how parents bring up children into their own psychoses and neuroses, in Egtverchi as much as the people of the Shelter society. Lithians don't look after their young; the process of development allows the Lithians to become at home in every type of ecosystem present on their planet. On Earth, being looked after by his reluctant surrogate parents, rather than becoming a well-developed adult, Egtverchi behaves like a stroppy teenager, resentful of both his biological and foster parents. Ruiz-Sanchez and Michelis also fail Egtverchi as parents in multiple ways; Ruiz-Sanchez in particular being utterly unable to provide moral guidance to a creature who, were he in his natural environment, would not need it. In the end, Egtverchi escapes aboard a freighter bound to Lithia, a snake on his way to spread corruption to Eden.

The ending of the book is spectacularly bleak. Ruiz-Sanchez is not immediately excommunicated from the church, as he expects. The Pope shares his view that Lithia is demonic in origin, but rather than being a world of intelligent beings created by the devil, he views the entire planet as a hallucination designed to test people's faith, and insists that Ruiz-Sanchez perform an exorcism on the whole planet. Ruiz-Sanchez's exorcism coincides with the exact moment that Cleaver's mining for munitions goes catastrophically wrong, and the end result is the destruction of the planet. The clever thing about how Blish plays this is that depending on one's theological bent you can read this as you choose. Is Ruiz-Sanchez's exorcism responsible for destroying the planet? The important thing is that Ruiz-Sanchez believes so. Now, as a result of consistently doing what his moral code tells him is the right thing, he is damned again because he caused the deaths of Cleaver and his excavation team, who would have been unshriven at their death and so are damned as well, not to mention that he has wiped out an entire sentient race and his own alien foster son.

http://goldenapplesofthewest.blogspot.co.uk/2014/10/james-blish-case-of-conscience-1958.html