![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

10/10/2015

![]()

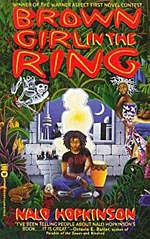

Nalo Hopkinson's Brown Girl in the Ring (2003) can be viewed two ways. From inside the ring, it defies tired urban fantasy tropes by employing a magic system based on Orisha, a Yoruba import embedded in some corners of Jamaican culture. This just might satisfy fans looking for a magic system that's not based on drugs or vampire sex.

From outside the ring, Brown Girl in the Ring feels just like any other urban fantasy: two-dimensional, limited, with predictable grit and cartoonish mobsters.

"This is a tough city, right? You people see a lot of terminal injuries?"

Seen, Rudy agreed wordlessly. Half the time, is we cause them. That amused him (4).

Near-future Toronto has become a "donut hole," where white flight bottoms out the downtown economy, leaving it starved, ravaged, with the leftover population abandoned to fend for themselves. Even medical services have gone underground. Inhabitants of this abandoned world, "the Burn," establish their own industries, from crime to unregulated food production, while others turn to drugs to self-medicate their consuming feelings of helplessness and depression.

It had been years since she had seen a working car... Sometimes it was hard to believe that there was even still a world outside(23-24).

Just before Baby's naming day, Ti-Jeanne notices that Baby seems to understand the surrounding world better than she. Ti-Jeanne's ex-boyfriend is caught up in the criminal activities of a local mobster, Crazy Betty wanders the streets, blind and mumbling unintelligible things, and everybody thinks Ti-Jeanne's grandmother, the local healer, fools around with the Obeah-- a kind of black magic. Ti-Jeanne doesn't know what to do about any of it.

Although it's often labeled as magical realism, Brown Girl in the Ring lacks the plenitude and ambiguity that defines that particular subset of literature. This is strictly a genre read that fits in well with traditional SFF stories that straddle the conventions of sci-fi and fantasy, and it certainly wouldn't be out of place in the hands of younger readers.

Rudy, the big bad mobster guy, is cartoony, especially when compared to the rest of the characters who exhibit more nuance (although I would have liked to see more depth across the board). This cartoonish depiction of Rudy derails the realism that Hopkinson is trying to create with her derelict setting and aimless characters. The story opens on Rudy's shady heart transplant negotiations; the tone feels cliché, and that flatness, unfortunately, taints the rest of the story. In so many ways, this could be a richer, deeper tale, but this is Hopkinson's first novel, and the complexity just isn't there. It's possible Hopkinson is going for a flat aesthetic, perhaps to mimic a childhood storytelling style, hence the nursery rhyme title, but the emphasis on horizontal dialogue to propel the story (and to let characters tell each other of things the reader needs to know) prevents the tale from reaching deeper planes.

Despite the plot's dependency on magic, it's not all fantasy. Science elements support the magic system, with most spells requiring some sort of herbal or medical expertise. The entire drama hinges on the Premier's need of a new heart, her preference being a human heart, rather than a controversial pig heart transplant, which is the current practice in this near-future setting. And there is, of course, the psychic Baby who seems to know his daddy is a loser long before his mother figures it out.

Brown Girl in the Ring could also be classified as horror, with Rudy's mobster arc tumbling into a gory, sadistic torture scene that involves flaying a woman alive, which almost made me throw up a little. (I'm a lightweight in the horror camp, and I was coming down with a case of food poisoning that I was unaware of at that particular moment. I probably would have appreciated the gore as a teen.) That device is repeated in the ultimate climax of the book, but it triggers more nausea than fear, only because the strands of BGitR feel too unreal to feel threatening to the reader. The suspense won't grip dedicated readers of gritty urban fantasy who are used to this sort of thing.

That said, Hopkinson does legitimately surprise with some unexpected character connections. There are a couple of unrelated character strands that reveal something far greater than random chance, which strengthens reader interest in the background of the story, though not enough to really deepen it beyond its two-dimensional content.

And, while some may applaud the realism of its portrayals of family and romantic relationships, in the wrong hands, this book could be criticized for reinforcing cultural stereotypes. Hopkinson's aim, at which she is successful, is to highlight people often left out of SFF stories; her goal is to cast the spotlight on--or put "in the ring," rather--people of color who make their homes in this rotting urban center. In BGitR every character is flawed, their social status limited, and they often make bad, predictable decisions that inevitably lead to tragedy for some. Anyone who harbors even the smallest prejudiced notions about immigrant and/or black Caribbean culture should never read this book. This book is not intended to defy cultural stereotypes, but to identify with potential young readers, to convey complexity about living on the disadvantaged end of a racist system, and to speak to and about those with limited status mobility. Hopkinson is subtle in this regard, and small minds won't get it, but it's for this reason that I look forward to reading more from Nalo Hopkinson, with the hope that her novels will deepen over time.

I devoted about 75% of this read to audiobook, narrated by the splendid Peter Jay Fernandez, who switches smoothly between a variety of accents and enlivens the fluent Jamaican-Canadian syntax with a rhythmic Caribbean flourish. (Anglophones who are not fluent enough to understand their native language in non-Anglophone accents won't be able to adapt to the quick-worded Jamaican tongue. And they don't deserve to listen to this book anyway.) But, while Fernandez treats the female characters with a neutral respect that I rarely encounter with male narrators, I would have preferred a female narrator of Jamaican descent, simply to provide more natural voicing for the primary protagonists, who happen to be female. (And I tend to pay more attention to non-Anglophone female narrators.)

And if you're wondering about the title, have fun YouTubing that one. And don't say I didn't warn you about its earworm potential.

"Brown girl in the ring... tra la la la la... she looks like a sugar in a plum..."

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com