Forays into Fantasy: Silverlock by John Myers Myers

Scott Lazerus is a Professor of Economics at Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado, and has been a science fiction fan since the 1970s. Recently, he began branching out into fantasy, and was surprised by the diversity of the genre. It’s not all wizards, elves, and dragons! Scott’s new blog series, Forays into Fantasy, is an SF fan’s exploration of the various threads of fantastic literature that have led to the wide variety of fantasy found today. FiF will examine some of the most interesting landmark books of the past, along with a few of today’s most acclaimed fantasies, building up an understanding of the connections between fantasy’s origins, its touchstones, and its many strands of influence.

John Myers Myers‘s Silverlock, published in 1949, is a recursive fantasy–a fantasy that makes use of settings or characters created by other authors, emphasizing the mutual influence and interrelatedness of all literature. Myers takes this conceit to its extreme, setting the novel on an island known as the Commonwealth–a reference to our shared inheritance of fictional and historical stories referred to by Joseph Addison as the "commonwealth of letters." In the Commonwealth, all stories coexist. The setting of Silverlock is all of literature and history!

John Myers Myers‘s Silverlock, published in 1949, is a recursive fantasy–a fantasy that makes use of settings or characters created by other authors, emphasizing the mutual influence and interrelatedness of all literature. Myers takes this conceit to its extreme, setting the novel on an island known as the Commonwealth–a reference to our shared inheritance of fictional and historical stories referred to by Joseph Addison as the "commonwealth of letters." In the Commonwealth, all stories coexist. The setting of Silverlock is all of literature and history!

In the first few chapters, Clarence Shandon, traveling on the Naglfar (the ship piloted by Loki during Ragnarok in Norse mythology), is shipwrecked. Assisted by Golias, who will become Shandon’s friend and guide, and who is also adrift in the ocean for reasons unknown, they witness the appearance of Moby Dick sinking the Pequod, after which they are able to make their way to the island of Aeaea, off the coast of the Commonwealth. Aeaea is the home of Circe (see Greek mythology for the details), who turns Shandon into a pig after he makes a pass at her. Golias helps him escape the island (and the influence of Circe’s spell), and they manage to swim to Robinson Crusoe’s island, where they are nearly captured by cannibals. Escaping in one of their kayaks, they nearly die of thirst before being picked up by a Viking ship, on their way to fight in the Battle of Clontarf (which took place when the Vikings invaded Ireland in 1014). Shandon is recruited as a rower, and he and Golias end up participating in the battle, barely escaping when the Vikings are routed. Separated from Golias, Shandon (now known as Silverlock, after the streak of premature gray in his hair) soon encounters Robin Hood and his men, helps Rosalette (a composite of Rosalind from As You Like It and Nicolette from the thirteenth-century French chantefable Aucassin and Nicolette) reunite with her lover, and joins the Mad Tea Party from Alice in Wonderland, among other adventures. After these travels, he manages to rendezvous with Golias, who is found in a tavern with Beowulf, celebrating the destruction of Grendel.

And all of this happens in the first third of the book. It’s the kind of novel that’s difficult to summarize without recounting too much detail, since it is so packed with incident and character, but I wanted to provide a taste of what the reading experience is like, and the way Myers combines story elements. A summary of the plot details, however, really misses the point. Instead, consider the main character. Shandon is a prototypical mid-twentieth century pragmatic American. When he is shipwrecked, he has little interest in saving himself, having become cynical and uninterested in life. "My only philosophy, if you could call it that, had been a contempt for life backed by a pride in that contempt." He is an educated man, but is clearly not the type to spend time with trivialities like art and literature. His arrival in the Commonwealth, however, plunges him into the world of stories, where he is ultimately transformed and enlightened by his exposure to the world of literature and history–in other words, the essence of human experience–and learns to reconnect with his humanity and regain a zest for living.

It’s not an easy path. At first he resists Golias’s attempts to involve him in his adventures. (I should note that Golias is a composite of various bard, minstrel, poet, and storyteller characters, and is referred to by many names throughout the novel.) He reluctantly agrees to assist a friend of Golias to claim his love and regain his inheritance, shamed into it by the presence of Beowulf, the ultimate hero. "Remembering what he had done to help out strangers, I simply could not let him hear me say that I would back out on a friend who was asking my help." The reform of his character has begun. The subsequent picaresque adventure occupies the second third of the novel, during which many other literary and historical figures are encountered. (Favorite incidents include an attempt to placate Don Quixote, and a trip on Huck Finn’s raft).

Mission accomplished, Golias unexpectedly tells Silverlock that they must separate. Shandon, who has finally gotten used to taking pleasure in the company of others, and thinks of Golias as his new best friend, doesn’t take it well, and his selfish reaction indicates that he still has some things to learn. Continuing to wander through the Commonwealth on his own, feeling bitter and cynical, his encounters become increasingly dark. He takes a ride on the Ship of Fools, runs into Job from the Old Testament (whose suffering makes it more difficult for Silverlock to feel sorry for himself), and is taken down into the Pit by "Faustophelese," where he encounters numerous examples of the dark side of human nature, along with other hellish denizens from various mythologies and Dante’s Inferno. His soul in danger, Silverlock is again rescued by Golias, now in the guise of Orpheus, and sent to drink from the spring of Hippocrene, the well of poetic inspiration in Greek myth. He doesn’t achieve the status of poet, but drinking from the spring allows him to remember his experiences in the Commonwealth, and receive passage back to his own world. He is taken aloft by Pegasus, and dropped into the ocean to be picked up by a passing ship.

Silverlock, then, is an allegory, but it’s much more fun than A Pilgrim’s Progress, as it includes much more drinking and singing. Shandon regains the joy of life, and Myers portrays that joy throughout. It’s a novel that shouldn’t work, yet does, and I put this down to the novel’s unique narrative perspective. The Commonwealth is not a fantasy setting in the usual sense. Those who read fantasy for the world-building aspect are likely to be disappointed, because this world makes no sense. Stories and characters from different historical periods coexist side by side, but the Vikings fight with bows, spears, and longships, oblivious to the fact that guns and steamboats are being used a few miles away. When Shandon encounters all of these characters and settings, he accepts them, never bringing up the fact that they are from stories. His pragmatic mind simply accepts the Commonwealth for what it is, and he never considers that his encounters seem designed to teach him lessons in living. This method allows the story to exist on several levels. The novel is narrated by Shandon, and from that direct perspective, Silverlock is a rollicking, rapidly-paced adventure story, full of excitement and interesting encounters, and can be enjoyed as such by readers mostly unaware of the literary allusions.

But for the reader with literary experience, those allusions provide another level of enjoyment. Since events are being described by someone entirely unfamiliar with the original stories, the reader must often identify the allusions without characters and settings being directly mentioned, but only described. For example, at one point Shandon and Golias find a raft and use it to travel toward their destination more quickly than they could on foot. The description of the river and their feelings while on the raft will identify it pretty quickly to anyone who has read Huckleberry Finn, but that story is never mentioned. Encountering Robin Hood or Don Quixote, Shandon doesn’t react by remembering the characters from a book or a movie, but his descriptions of their appearance and behavior will identify them to those familiar with the stories.

And I can guarantee that no reader will be familiar with all the stories. Nearly every detail in the book is taken from another story. Knowing that, I found myself continually trying to figure out the sources based on the descriptions in the novel, since they are not directly identified, and are often composites of similar characters from different stories (as in the case of Golias). This literary guessing game will be an enjoyable challenge for some readers, and is a big reason for the book’s cult following. Anyone trying to "get" all the references is bound to be disappointed, but the wonderful thing about Myers’s narrative method is that the novel can be enjoyed without getting them, so the reader can engage with that aspect of the novel to whatever degree she cares to.

And I can guarantee that no reader will be familiar with all the stories. Nearly every detail in the book is taken from another story. Knowing that, I found myself continually trying to figure out the sources based on the descriptions in the novel, since they are not directly identified, and are often composites of similar characters from different stories (as in the case of Golias). This literary guessing game will be an enjoyable challenge for some readers, and is a big reason for the book’s cult following. Anyone trying to "get" all the references is bound to be disappointed, but the wonderful thing about Myers’s narrative method is that the novel can be enjoyed without getting them, so the reader can engage with that aspect of the novel to whatever degree she cares to.

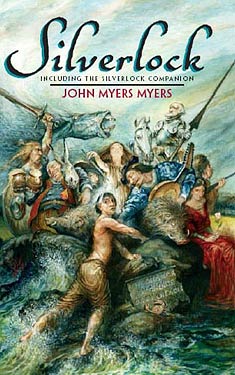

For anyone thinking of reading Silverlock, I strongly recommend getting the NESFA Press edition, which is still in print, since, along with being a beautiful book, it contains The Silverlock Companion, a hundred and fifty pages of supplementary material including, most importantly, "A Reader’s Guide to the Commonwealth," a concordance of the literary allusions. Coming across an unfamiliar character or place, it can be looked up in the guide and the original source identified. Along with discovering literary antecedents I was unaware of, or only vaguely aware of, this additional background added to my understanding of Myers’s reasons for choosing the stories for Silverlock to interact with, in relation to his own progress as a character. Browsing through this compendium of eighteenth and nineteenth century novels, Greek, Norse, Irish, Icelandic, and Chinese myths and legends, American tall tales, and Old English poetry, Myers’ amazing achievement is brought home. (And those examples just scratch the surface. There are hundreds of stories referenced in Silverlock.) His goal, however, is not to point out his own erudition, but rather to celebrate the role of stories in our lives. His story–Silverlock–is just one more small region to be annexed by the Commonwealth. Instead, he wants to remind us of the beauty–dramatic, comedic, tragic, romantic, fantastic–of the literary and historical heritage of humanity. Like Shandon, we can’t stay in the Commonwealth forever, but visiting it will enrich our lives by providing access to people, ideas, and experiences that enrich our understanding and enjoyment of life.

So, where does Silverlock fit in the history of fantastic literature? As mentioned above, it can be seen as a major exemplar of recursive fantasy, and many of its sources are the wellsprings of the fantastic–ancient myths, fairy tales, Arthurian legends, Beowulf, Dante’s Inferno…–thus being in a sense a fantasy about the fantastic. But since the narrator, Shandon, is unaware of the nature of the fantasy world he has entered, it does not come across as self-aware metafiction. As far as I know, then, Silverlock is unique in the history of fantasy. While there are plenty of other examples of recursive fantasy (Myers was probably influenced by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Incomplete Enchanter, for example), none that I know of operate in the way the Silverlock does. (If anyone knows of anything similar, I’d like to hear about it.)

Its uniqueness may explain its relative obscurity. As Myers wrote in 1980: "This was to be my big book, my contribution to the ages, and it flopped all over the place. Although it has since been revived by Ace in 1966, and again in 1979–it was an egg laid by an ostrich when it first came out and was remaindered." It’s been championed by its fans–Poul Anderson, Larry Niven, and Jerry Pournelle each wrote introductions to the 1979 edition–but it seems to be something of a cult item today, not well known to the community of fantasy readers, but extremely well-loved by those who do know it and appreciate it. According to David Pringle, who includes it in his Hundred Best, Myers "has produced a strange, harshly whimsical and rumbustious book… It will not be to every reader’s taste, but it is memorably different."

Its lack of success may have had to do with its timing. Prior to the 1920s, fantasy as a genre had yet to be ghettoized. Hawthorne, Melville, Henry James, Mark Twain, and Jack London all wrote fantasy without readers raising an eyebrow. It was just one of a number of fictional strategies used by these writers. By the time Silverlock was published, however, fantasy had mostly been relegated to the pulps. Silverlock, as a literary fantasy arriving in 1949, was ignored by the mainstream, simply because it was fantasy, while not being the sort of thing to interest the majority of the genre audience. In retrospect, we can ignore the genre prejudices and see it as part of a larger flowering of fantasy in the ‘40s and ‘50s that included, in America, de Camp and Pratt, Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser sequence; and, in the United Kingdom, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, and, of course, J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Despite being the least well-known of these contemporaries, it deserves to be considered among them.

Full Details

Full Details

3 Comments

Silverlock sounds like a fun read. I really love the "identify that reference" game in my reading and movies etc. so this sounds right up my alley. I don’t usually get all the classic literature references but when I do it makes me feel oh so clever. I’ll definitely get the NESFA edition so I’ll have the Reader’s Guide to use as a score card. Great review as always, Scott!

Sounds like a pretty wild ride. How has the prose itself held up in 50 years since initial publication?

Dave: I might have gotten a quarter of the references. Looking through the reader’s guide afterword was pretty humbling for someone who thinks of himself as pretty well-read! The good thing is that the story works fine, regardless of how well you catch on to that aspect of the novel. Mattastrophic: I’d say Myers is a cut above the usual genre writing of that period. He’s actually better known for his historical works about the American West, and explored the possibilities of narrative poetry throughout his career. Here’s how David Pringle describes the writing: "written throughout with a slangy, mid-twentieth-century American style, a style redolent of cracker-barrels, Tall Tales, and the tradition of so-called South-Western humor. It also contains an underlying streak of brutality which is not untypical of those rude influences." That strikes me as a bit exaggerated, but you definitely get the sense of an odd juxtaposition between the narrative style and the subject matter. Like everything else about it, it’s unique and hard to compare to anything else.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.