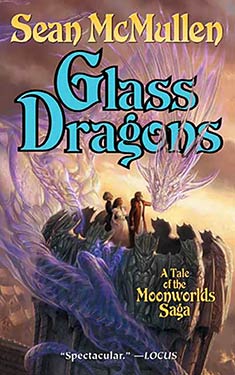

Glass Dragons

| Author: | Sean McMullen |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2004 |

| Series: | The Moonworlds Saga: Book 2 |

|

1. Voyage of the Shadowmoon |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Sean McMullen, one of Australia's leading genre authors, delivers Glass Dragons, the scintillating sequel to Voyage of the Shadowmoon which Kirkus Reviews called "a brilliantly inventive, marvelously plotted sea-faring fantasy that both mocks and surpasses genre expectations.... Australian author McMullen writes like Roger Zelazny at the peak of his powers: his dashing, flamboyant, cleverly resourceful characters trade off insults and reveal surprising abilities as they swagger bravely from one hair-raising scene to another. Exciting, suspenseful, vividly believable, and great, clever fun: a major fantasy-award contender."

Glass Dragons continues the tale of Laron, the chivalrous 700-year-old vampire, the appallingly dangerous and beautiful Velander, and the long-suffering Terikel, as they investigate a secret project of arcane magic, a magic so dangerous it could destroy their world. A project which threatens to fall into the wrong hands.

Glass Dragons is a broad and complicated tale, filled with wonderful characters both new and old, woven through with low humor and great courage, built upon grand acts of heroism and love. Enjoy.

Excerpt

Chapter One

DRAGONSCHEME

On the night of the wedding of Princess Senterri to Viscount Cosseren, there was one thought that could not have been farther from the mind of the Master of Royal Music to the Emperor of Sargol. He had heard the saying Great elevation brings the danger of a really, really long fall, but he was sure that it could never apply to him.

Milvarios of Tourlossen had no real political power. He merely had to look dignified and make sure that nothing went wrong with the music to be played on important occasions. Being Master of the Royal Music meant that one had to know the emperor's tastes in music, be an excellent and efficient organizer of events, know which bards, minstrels, and players were in favor or on the way up, know all the court intrigues and gossip, dress well, and be able to hold one's drink. One very seldom had to sing, compose, or play an instrument, but this suited Milvarios, because he did neither of the first two particularly well, and did not play any better than those he hired to play for the emperor. He was, however, a meticulous and efficient organizer.

The wedding music had been played without so much as a single sour note, broken string, or missed cue. The ceremony itself took place in the palace temple, and required brass bands for the processions, marches, and fanfares. The lavish reception in the throne hall featured a string consort for the feasting, and a woodwind band for the dances. None of that was as exposed as the music in the temple, so that even though the night was not quite over, Milvarios was already beginning to relax. He had spent eleven hours either posing with nobles and royalty as solemn words were chanted, or frantically scurrying about behind the scenes waving schedules, and making sure that dozens of musicians and hundreds of singers were in the right places at the appropriate times, and all with the correct music in front of them.

The career of Milvarios of Tourlossen, Master of Royal Music, had precisely nine minutes and fifty-seven seconds to go before experiencing a quite catastrophic and spectacular termination.

* * *

Elsewhere in the palace, a tiny problem had emerged that had the potential to sour the occasion far worse than broken strings or missed cues. The bridal suite of the newlywed couple was in a tower that overlooked the harbor. The tower had been emptied of all servants, guards, and courtiers, and the base was heavily guarded. All of this was to guarantee privacy to Senterri and Cosserin for the night that was to be theirs and theirs alone.

Viscount Cosseren had a physique that many young women swooned over. Being from a family of considerable means, he had spent much of his life riding, hunting, and learning to excel with every weapon deemed suitable for a gentleman. Most courtiers agreed, however, that he had probably forgotten to stand in the queue when common sense was being handed out. Still, being too stupid to be ambitious or rebellious had a certain attraction about it as far as the emperor was concerned. As far as Princess Senterri was concerned, it was a very different matter. She was sitting naked on the enormous matrimonial bed, her arms wrapped around her legs while she sobbed behind the veils of brunette hair that concealed her face.

"I have never, never been so insulted!" muttered Cosseren as he laced up his shirt. "Not a virgin! I know about virgins, I've bedded dozens, there's nothing you can teach me about virgins. Why, and, and you, lost it to a common slaver, too!"

"My lord, please listen!" Senterri pleaded. "He was my rescuer, not a slaver."

"Slaver, rescuer, what difference does it make? You have been defiled by some upstart of low degree."

"He was a gentleman."

"Gentleman! A mere kavelar can be called a gentleman. What was his family's estate?"

"He was from North Scalticar--"

"A foreigner too! I am going, and I am sure that your father will be very interested to hear how you lied about your, ah, honor's status."

Cosseren strode to the door, flung it open, and slammed it shut behind him. He had taken only a dozen steps when something detached itself from the shadows of an arched brickwork vault and knocked him to the stone floor.

Viscount Cosseren awoke to find himself staring into a very pale face. The thing's eyes flickered with just the trace of a bluish glow, and its mouth was slightly open in a shallow smile. Cosseren had a vague impression that it was a girl of some description. He also wished that she were not smiling, because it exposed her two upper canine teeth. They were three times longer than they should have been, and they also glowed slightly. Although she was lightly built, she was holding Cosseren by the throat, at arm's length, with one hand. The young viscount glanced down. The drop to the courtyard was at least a hundred feet. There were guards patrolling there, but none were looking up. There was a suggestion of mildew and rotting meat in the air.

"Senterri, is upset," the apparently female daemon declared in a silky whisper. "You caused. Senterri, my friend."

"Who...you?" managed Cosseren.

"Myself, am very evil. Senterri nice to me, once. Grateful. Senterri, you hurt."

"Szzoorrgrinniy," the rapidly choking Cosseren answered as the grip on his throat tightened.

"Having any idea, how more strong, than you, am being?"

"Gnnng."

"Not drop you. Is only terror, for making. But..."

"Bnngeg?"

"But if not return Senterri, grovel, say sorry, do sexing, then..."

"Genng?"

"Rip throat. Suck blood. You, long time, for dying. Body never will found, be. Senterri merry widow, be. Or is joyous widow? Happy widow? Adjectives confusing."

Just around a nearby corner stood Senterri. She wore nothing but her hair and tears, and had been intending to run after Cosseren and plead with him not to dishonor her to her father. Now it had become obvious that her very strange friend was doing some rather more persuasive pleading. Cosseren was dragged back through the window and released. His wheezing gasps went on for quite a long time.

"You, to Senterri, back, go," said the menacing, silky voice with the strange and heavy accent. "If not return, I return. If Senterri sad, I return. If Senterri angry, I return. If no grovel, I return. If no sexing, I return. For you, very bad, if I return."

* * *

As he glanced at the common musicians in the string consort, Milvarios sneered in a discreet sort of way. In spite of the fine clothing they had been given, they still contrived to look just slightly scruffy. Some already looked drunk. On the other hand, Milvarios left nothing to chance, and he had selected his musicians for their ability to play well while drunk, as well as their ability to play well in the first place. One day his efficiency would see him rise to be seneschal of the imperial palace, he was sure of that.

For some reason Milvarios found himself staring at the man playing the angelwing lyre. He was tallish, with a neat black beard, curly hair, brown eyes, and long, thin fingers. He might have been the very image of Milvarios had he been about sixty pounds lighter. The man looked up and locked stares with Milvarios. There was suddenly something very alarming about him.

"My lord has had a great triumph tonight."

Milvarios turned to be confronted by a woman about ten years his senior. Other gentlemen of the court and diplomatic service had been paying her no heed, but Milvarios was motivated rather differently from the others. By paying court to women of palace society who were just a little past their prime, Milvarios generated goodwill, and had people speaking well of him when he was not there to speak well of himself.

"My lady Arrikin, you are a triumph by your very presence," responded Milvarios, bending to kiss her hand.

Widow, daughter soon to be married, spending massive amounts of gold on the wedding, wishes to impress the court, late husband made a fortune in camel-caravan speculation and bought a peerage flashed through Milvarios's mind.

"The emperor can certainly afford the best of everything," said Lady Arrikin, with a wave of her fan at the musicians.

"Ah, but I believe your most supremely lovely daughter is to be married next month. You must take care not to overshadow this lowly spectacle, you know what the penalties for treason are like."

Lady Arrikin smiled demurely. "It was on that very subject that I wished to speak with you. What would you charge to put your quill to a bridal anthem?"

"My lady!" exclaimed Milvarios softly, placing a hand across his chest. "My quill may be put to use for no other than the emperor."

"My lord Milvarios, I am sure there are certain uses for your quill that the emperor would rather not know about," replied Lady Arrikin with a discreet flutter of her eyelashes.

"Well...perhaps I could at least share some inspiration with you in, perhaps, one hour, once the feast has reached a stage that requires no more supervision?"

"In your chamber, then, Lord Milvarios?"

"I could not countenance the delay of a journey to some more distant tryst, most excellent lady."

As he took his leave of her, Milvarios cast a glance over the musicians. All was well, except that the angelwing lyre was leaning against a chair, and its musician was nowhere to be seen. On the other hand, nobody seems to be paying much attention to the music by now, so there is no harm done, thought Milvarios. My triumph is still complete.

Except for the music, the wedding had been plagued by tiny, annoying problems. The acrobat who had leaped out of the cake modeled after the royal palace had stumbled, but not actually fallen. The groom had answered where the bride should have spoken in several parts of the ceremony. One of the horses in the guard of honor had voided its bowels during the fifty-yard parade across the courtyard from the palace temple to the reception portico. Only my music has been truly without flaw, thought Milvarios over and over. The emperor had been pleased indeed, and had promised to make him Herald of the Declaration. Now Milvarios had a bedmate to impress for the rest of the night. Although she was a little older than some might prefer, her skin was flawless and she was rumored to diet--and even exercise--in order to preserve her allure.

While Milvarios could not actually sell an anthem to Lady Arrikin, he could write it, then let rumors free that he might be the composer. By protocol and convention, he was then free to refuse to comment rather than flatly deny those rumors, implying that he had composed the anthem. This also implied the emperor's favor to the woman's daughter, which was the whole point of the exercise. The irony was that the anthem did not even have to be very good, as long as he refused to deny that he wrote it. At the very worst, Milvarios would spend a very pleasant night with Lady Arrikin, then pay some starving music student to ghost-write the anthem. Glancing around one last time, he decided that everything was going smoothly. Most present were getting drunk, eating too much, and flirting with each other's partners. Milvarios managed to catch the attention of the emperor, and was beckoned over.

"My lord musician, where would I be without you?" the monarch said softly as Milvarios bowed before him. "Such a myriad of petty annoyances with the wedding. Does it portend a similar clutch of vexing little problems with the marriage itself?"

"I cannot say, Your Majesty. I am a musician, not a seer."

"Only your music was without flaw. Now, surely you could read a meaning into that?"

"Perhaps..." began Milvarios, thinking very quickly. "Perhaps it means that the marriage will indeed be plagued by vexing little problems, but the couple will live in harmony in spite of it all."

The emperor smiled, then chuckled. It was his first sign of mirth for all of that day.

"Tell me, most harmonious friend, what is your experience of seneschal work?" he asked, smiling up at Milvarios.

"A music master must also be a seneschal, Your Majesty, but a seneschal need not be a musician."

"Oh clever, Milvarios, very clever. Now then, why did you want to see me?"

"I hoped to be granted leave to retire for the night, sire."

"Certainly, go to your bed at once and sleep deeply. I shall have some extra duties for you tomorrow, attend me at the hour before noon. Perchance you can bring some of your harmony to the running of the palace."

Milvarious felt that he was walking on air as he slipped away to prepare his quarters for his visitor. This would involve scattering important-looking scrolls and declarations about, for her to chance upon and find impressive, but soon his mere name would be vastly more impressive. The emperor was to appoint him as palace seneschal in a mere twelve hours.

He was not to know that the emperor had a mere three minutes and fifty-seven seconds to live.

* * *

Senterri hurried silently back to the matrimonial bedchamber, climbed onto the bed, and sat waiting for her husband to return. Presently she heard the cautious tread of leather-soled riding boots outside. The footsteps slowed. They stopped. A hand reached around and tapped on the open door.

"Yes?" said Senterri in a clear, sharp voice.

"Er, dearest petal, I, er, thought it over," said Cosseren, sidling into view.

"So I see," responded Senterri sternly.

Cosseren had thought that she would be almost hysterical with relief that he had returned. Senterri was not, in fact, sounding at all hysterical. This did not bode well.

"And I decided, that, well, you are so lovely that I could not dishonor you, so I have decided to forgive you and return to your bed."

Senterri turned her head to one side.

"That is a very sweet story," said Senterri, "but the finger marks on your throat tell me a rather different tale. I think that you have met a friend of mine, a friend who can climb sheer walls, is stronger than you and your horse combined, and has some awfully unsettling eating habits."

Cosseren put a hand to his throat and glanced hastily over his shoulder.

"Look, I, er, really am sorry," he replied. "Very sorry. Desperately sorry."

"Oh, but you will soon be sorrier, much, much sorrier," rasped Senterri. "You may not have had the chance to dishonor me in front of anyone else, Viscount Cosseren, but dishonor me you certainly did. Bedded dozens of virgins, have you? Well, if you so much as smile at another woman's portrait from now on, I shall be very angry. Do you know who will return if that happens?"

"Ya-ya-yes."

"And what is more, you will--as my daemon friend put it so charmingly--'do sexing' with me six times a night--"

"Six times? I say--"

"--until I become pregnant. Now take off your clothes and get into bed."

"Yes, my petal bowl, at once," babbled the viscount, kicking off his boots and literally tearing off his shirt. "But, but, six times!"

"Think of someone else if it helps, I shall certainly do so."

"Whatever you say, delight of my eyes."

"And Cosseren!"

"Yes, my petal storm?"

"That first time did not count for tonight."

* * *

Milvarios turned the ornate, three-tumbler key in the lock, then pushed the door open. It was as well never to rush through any palace door, especially one that had been locked. One might disturb someone in the process of making off with the silverware, and people of that kind tended to be armed. Milvarios glanced to the gold coin that he always left on the table. Were that missing, he would have pulled the door shut, locked it, and screamed for the guards. The coin was still there, however, and all that was moving within his suite of rooms was the flames in the fireplace and the shadows they cast on the walls. He entered, glanced about, closed the door, and turned the key in the lock.

Halfway across the room, he suddenly realized that the gold coin was no longer on the table.

"Oh dear, I forgot to order a jar of expensive wine for my beloved and I to share tonight!" exclaimed Milvarios in a voice that bordered on a shout, had suddenly become highly pitched, and was on the very edge of hysteria.

He turned, and was confronted by a rather thin, bearded mirror image of himself. The image slammed a fist into his plexus. The wheeze that Milvarios gave as he doubled over was barely audible. With the skill of one who did that sort of thing for a living, the intruder guided Milvarios down to lie in front of the hearth, then tied his wrists after looping his arms through the heavy iron bars that stopped burning logs from rolling out onto the floor. Next he gagged him, then tied his ankles.

"You came back a little early, Milvarios," said the intruder as he peeled off his beard. "I had expected you to spend at least another half hour brown-nosing with the emperor, but no matter."

Milvarios watched as the intruder lifted his robes and began to insert a framework of cane slats beneath. In a very short time the slats took the form of about sixty pounds of good living, and with the man's robes back in place and smoothed down, there was nothing to distinguish him from the Master of Royal Music in either form or face.

"You are probably wondering who I am," said the intruder in a soft, casual voice. "I cannot tell you that, but I can tell you about my identity. Actually, I stole my identity. It belonged to a peasant, but he was not making very good use of it."

The intruder walked out to another room, then returned with a small crossbow and a basket of flowers. Milvarios watched him cock the string, pour something from a phial onto a bolt, then load the weapon. He was a little puzzled when the intruder started clipping flowers onto the weapon, but suddenly he understood his purpose all too clearly.

"Who I am is of no importance, however," said the man who was not a peasant. "The peasant who provided my identity is working hard for the first time in his life, feeding the fish about half a mile out to sea, and may he have a good story for the gods to explain his transgressions in life. But enough of him. I used a very powerful casting to make my flesh as dough; then I fashioned my face to pass for yours. Now I shall become you for a minute or two, kill your monarch, then become the dead peasant again. You see, Milvarios, I do not exist."

He inspected the crossbow, which now resembled a bouquet.

"As I return, I shall accidentally lose my hood and cloak, and be recognized as you. Before I unbind you and remove that tiresome gag, I shall then pour a particularly subtle poison into your ear. The poison will soon have you crazed with pain, and you will go thrashing about and screaming as if in a rage. The guards will think you are fighting them, and they will kill you. Alas, Milvarios, I would like to leave you alive to face the wrath of the soon-to-be crown prince, but I cannot have you telling people to search for a peasant with your face, can I? You know, I do look forward to this part of each assassination. My reluctant doubles are the only people that I can ever tell about my skills and methods, and I do enjoy performing to an audience. No, please don't bother attempting to applaud."

He left. Milvarios looked about frantically, but saw nothing nearby that could aid him. He strained against his bonds, but his captor had done his work well, and they were as tight as a harp string. He could barely move; in fact, the early stages of cramp were taking hold of his left calf. He stretched his legs. This had the effect of pushing his hands closer to the flames. He quickly drew his legs back...then he stretched them out again, and extended his hands to the fire. Some blind scrabbling soon had a partly burned log extracted. He turned it so that its hot coals were facing him, then pressed the cords binding his wrists against the coals.

Milvarios was not used to discomfort, and he flinched away from the sharp, bright pain of the red-hot coals; then he reminded himself that the alternative to a little burned skin was death. He pressed his bonds against the coals again, and again, and again. The cords binding Milvarios's wrists began to char. So did his wrists. He squealed with pain through his gag, but such was the noise from the nearby revel that nobody could have heard him. There was the scent of burning cloth, burning hair, and burning meat. Suddenly he felt the bonds give a little. They snapped. As he sat up, Milvarios saw that quite large areas of both wrists were blistered and even charred. Not nearly so much of me as will be charred if I wear the blame for the emperor's death, he thought as he pulled the gag from his mouth.

"Murder!" he shouted. "The emperor's to be murdered! Warn the emperor!"

There was no response. Too much noise from the feasting and music, he knew. He undid the bindings on his ankles and stood up, then fell down again because his legs had lost circulation. The distant music and singing became screams. He's done it, thought Milvarios. He's done it, and as me!

For a moment the Master of Royal Music lay rigid with despair; then despair became outrage. The assassin was going to make sure he was seen running about with a crossbow, and then he would come back to the room, grab his disguise, and be gone. It was not fair! Milvarios picked up a poker from the fireplace.

He is a master assassin with any number of deadly weapons, thought Milvarios. I am a musician with a poker. I have about as much chance of taking him by surprise and hitting him over the head as I have of winning the Dockside Topless Hoyden of the Month competition. So what to do?

He dropped the poker. The assassin would have a way to escape from the room, having led the guards back there. How? Where? Milvarios suddenly remembered that there was a lover's hide behind a secret panel, but he knew that it led nowhere.

Somewhere in the distance he heard a female voice shriek "Milvarios!," then another crying "Milvarios, what have you done?"

Even though it led nowhere, the lover's hide had the advantage of being the only hiding place that was unlikely to be searched within the first quarter minute of the guards arriving. Milvarios crawled across the floor, and was through the secret sliding panel and sitting silently in the darkness within the time it took to draw five breaths. He heard the door's outer latch rattle; then there was a slam as it was shut. The inner latch rattled as the assassin bolted it from the inside.

"Now, Milvarios of Tourlossen is about to go free, but not for long--" began the assassin.

He had noticed that the Master of Royal Music was no longer there. Milvarios heard a brief and enthusiastic clatter as the assassin made a frantic search of the bedchamber and other rooms. Fists began pounding on the door, gruff voices called upon Milvarios to surrender. The assassin finally thought to abandon the search for his scapegoat and merely escape. Fingers scrabbled against the filigree fretwork of the sliding panel and pressed a hidden release. The release did not release, however, and the panel certainly did not slide. Milvarios was holding the mechanism very, very tightly from the inside. There were soft but intense curses from the other side of the panel, curses in some foreign language.

A loud crash reverberated as the door burst in, followed by the sounds of blades clashing and furniture being smashed. Screams and groans were mixed in with the sounds of the fight, and from the general tenor of the cries, it was apparent that the assassin was winning.

"Stand clear!" someone called, then added, "Shoot!"

There was a patter of loud snaps as the guardsmen's crossbows spat their bolts at the assassin. For some moments Milvarios heard little more than boots tramping on the shattered remains of his expensive crockery; then a voice announced, "The traitor is dead." Milvarios sat listening to the guards talking while they waited for someone to persuade their senior officers that the assassin really was dead.

"Who would have thought it, a fopsie like him."

"Killed five of us."

"Game bastard, fought like a daemon."

"We're lucky we killed him."

"Lucky for him, you mean, penalties for regicide being what they are."

"Would've been hung by his toes over a slow fire."

"Aye, while his ballads was read to him."

"So, you had to stand guard at his readings too?"

"Ye know, it makes sense. Such a terrible balladeer turns out to be a master assassin."

"Aye, a man can't be bad at everything."

Milvarios slowly released the mechanism and lowered his hand. His fingers found clothing--and the string of some instrument! The soft note was as loud as a thunderclap to Milvarios, but was not heard by the guards. Very carefully he examined the thing that had very nearly betrayed him. It was a board lyre, a commoner bard's instrument. He decided to stay hidden for a few more moments, at least until the officers arrived. Guards tended to do hasty things in the heat of the moment, and he was not convinced that the moment was sufficiently cool for him to emerge. There were sounds of feet approaching, and someone shouted "Attention!" Boot heels clicked, and there was a brief silence.

I'll make sure that every man in this room stands guard at my readings until his dying day, thought Milvarios as he sat shivering in the narrow, drafty space.

"He looks dead," said a cultured voice.

"Crossbow bolt through the forehead is always hard to argue with, my lord."

"Is he safe to approach?"

"I'd bet a month's wages on it, my lord."

"Look at this! Cane hoops and frames under his clothes. A thin man disguised as a fat man!"

"Amazing. With all the food he scoffed down, you'd think he'd be fat without any help."

There was another pause.

"Prince Stavez is furious. He ordered the Tourlossen mansion and warehouse burned."

The moment is still hot, thought Milvarios.

"Surely the elder Tourlossen would protest."

"The elder Tourlossen would require a head for that, and likewise his wife. Their other two sons are abroad, and I doubt they will ever be back."

"Give me your crossbow, I must report the assassin's death to the prince."

The sound of receding footsteps reached Milvarios.

"Bastard's thinking to take credit for the kill himself."

"Aye, and he will."

The moment is being lowered into a volcano, Milvarios decided. Surely someone knew he was genuinely fat--of course! The wife of the Clerk of Provisioning, who was his secret lover. Secret, that was the tricky word. Not only would she be unenthusiastic about her husband finding out about the liaison, she would be even less happy about being associated with a man accused of murdering the emperor. No, being fat would not help Milvarios.

One movable panel of wood was separating him from the attention of the guards. Should he slide the panel aside, they would want to know. Know what? What was the worst thing that they could ask? Why had he hidden quietly in his room while the emperor was being murdered? Why--no, that first why was sufficient.

Milvarios took stock in the light leaking past tiny cracks in the woodwork. Aside from the robes he was wearing, he had on hand one pair of grimy, roughweave trousers, a pair of reeking boots, a tunic stained with red wine, a woolen cloak, a half-empty wineskin, and a board lyre. He reached forward for the boots--and something batted softly at his face. Milvarios nearly screamed with terror, then realized that it was only a dangling rope. He groped above his head, and discovered a circular hole cut in the hide's roof. This was how the bastard entered my locked suite, Milvarios realized. It is also the way he intended to flee.

The presence of an escape route changed everything. Milvarios also had the knowledge that Milvarios of Tourlossen was safely dead, and that nobody was currently looking for Milvarios of Tourlossen. He examined the assassin's disguise in more detail. A grimy drawstring purse contained a few coppers, and a city gate pass scrawled out to Wallas Gandier, goatherd. Very slowly, and in complete silence, Milvarios began to ease himself out of his own robes and into the dead goatherd's clothing. The trousers were a tight fit, and that of the tunic was not much better.

"Will ye look at this?" exclaimed someone on the other side of the panel.

"Gold!"

"Lots of gold."

"It's the assassin's fee, that's for sure."

"And a right generous fee. Feel the weight."

"Surely a coin each would not be missed."

"Among five of us?"

"Still not much amid all this."

"Two for me, I killed the assassin."

By the time Milvarios of Tourlossen had become Wallas Gandier, each of the guards had seventeen gold coins and the leather pouch was burning in the bedchamber's grate. One of the more literate of them had written "Death to the emperor who seduced my beloved" on a sheet of reedpaper and left it in the chest where the gold had been found.

"What I can't think is why he fled here, where he's been trapped."

"There's a secret panel somewhere, what slides aside. Bet he meant to hide there."

"How d'ye know?"

"All the palace bedchambers have 'em. They're to hide lovers in, like when husbands of wives show up at the door unexpected."

"But how d'ye know of 'em?"

"Well, I've had occasion to make use of a couple."

Time to move, thought the former Master of Royal Music. He slowly straightened. The space was small; in fact, it appeared to be an old built-in cupboard that had been converted into a hide. There was a roughly cut hole above his head, however, and through it dangled the knotted rope.

While the guards poked and pressed at the filigree work on the panels, the man who was now Wallas hauled himself up the rope left by the assassin. The space was narrow, and he was both broader than the assassin and unused to climbing. The rope was tied to a beam, but above the beam were boards. He pushed, and found that the boards were not nailed down. He climbed out into a portico that led out onto the battlements. Wallas replaced the boards and stepped outside, just as the sound of tramping feet sounded from around a corner.

Thinking faster than he ever had in his life, the former Master of Royal Music sat down on the edge of the outer wall and strummed the board lyre. It was badly out of tune, which did not surprise him at all.

"The great emperor, wise and old,

Struck dead by an assassin bold.

The deadly Milvarios, full of stealth,

Betrayed his emperor for golden--"

"Hey! You! Halt!" barked the squad's leader.

Because he had not been moving, the newest bard in all of the Sargolan Empire stopped playing instead.

"What are you doing here?" the marshal of the squad continued.

"I'm composing a lament for the dead emperor," replied the grubby intruder.

"I mean how did you get up here?"

"By the stairs."

"The stairs were guarded."

"No, my lord, you ordered all men to the Master of Royal Music's chambers," said his corporal, who was holding the squad's torch.

Wallas gestured to the overcast sky without looking upward, then strummed the board lyre.

"I came here to compose between the mighty strength of the battlements and the frail beauty of the stars," he declared. "While the horror of the assassination's moment was fresh in my mind, I sought to call upon the muse of my art to--"

The marshal placed a boot on Wallas's chest and pushed. Wallas tumbled from the battlements, and screamed for the entire sixty feet to the dark and rank waters of the moat.

"Some people just don't appreciate art," said the marshal as he looked over the edge with his hands on his hips. Then he strode away with his men.

* * *

Still clutching his board lyre, the new Wallas crawled out onto the mud at the edge of the moat. He then vomited up his dinner, some very expensive mulled mead, at least three pints of reeking moatwater, and half a dozen tadpoles. The perimeter guards now came running up. He was frog-marched to a servants' gate in the outer promenade wall of the palace grounds, then sent on his way into the city beyond with a hefty kick. He hurried away into the dark and forbidding streets, but by now it was raining again and the more dangerous urban predators had retired to the taverns.

By just walking aimlessly Wallas eventually came to the river, and one of the three stone bridges that spanned it. The bridge appeared to be burning, but only because a couple of dozen beggars had a driftwood fire on the bank beneath.

"Hie, bard, join us!" someone called, and Wallas needed no more persuasion than that.

"Thee be wet," observed a beggar as he joined the circle on the mud.

"Jumped in t'moat of palace," he replied economically, aware that his educated speech was the single flaw in his disguise.

"And why was that?" asked a streetlord, who was wearing a crown made from scraps of rubbish held together with string.

"Were set on fire," Wallas said, holding up his wrists to display his burns.

"And why was that?"

"Some bugger said me music were not bright enough," replied Wallas ruefully, and they all laughed at what may or may not have been a joke.

"Now what would ye have for us?" asked the streetlord. "What say a tune?"

Wallas thought fast. A bard who could not play his own board lyre would be the occasion for comment. On the other hand his wrists were badly burned and his lyre was wet.

"The catgut got soaked as I swam, so there's no tune in me strings," he replied. "And me wrists are roasted."

There was silence. The silence lengthened. Clearly Wallas was meant to contribute something. He thought of the purse on his belt, which contained a few grubby coins.

"What's the skin, then?" asked a beggar beside him.

"Wine from the emperor's table," said Wallas at once.

It had probably been wine from the musicians' servery, but nobody present was in a position to know that. He offered it to the beggar streetlord, who accepted it with undisguised delight. Wallas was now guaranteed a refuge for the night. A beggar who claimed to have once been an herbalist rubbed a reeking paste onto Wallas's burns, then bandaged them with strips of sacking. While he sat steaming his clothes dry by the fire, Wallas entertained the company with descriptions of the royal wedding--and subsequent assassination--as they sat passing the wineskin around. In turn, Wallas learned how to gut, skewer, and roast a rat, along with several songs about beggars, lamplight women, sailors, and getting drunk on very cheap wine. Wallas was relieved to discover that the soaking in the moat had allowed his trousers and tunic to stretch to accommodate his size a little better.

Dawn saw the rain at an end, and a heavy mist on the river. Even though Wallas's clothes were now dry, they were cheap and coarse, and they stank. His woolen cloak did double as quite a reasonable blanket, however, and the beggars had kept the fire alight all night. He again took stock. He had the clothes that he was wearing, a purse containing four copper demis, a small knife, and a board lyre. Some twelve hours after acquiring the instrument, he finally looked at it more carefully.

As its name implied, it was a board that had been cut into a lyre. It had no sound box, only five gut strings, three bone frets, and the wooden pegs. It was designed to put out just enough sound to be heard within a few feet. It was also designed to be virtually worthless but practically unbreakable. Were it ever to be stolen, one could always build another as long as some scrap wood and a slow cat were within reach. The problem for Wallas was that he could not play it. The former Wallas could probably do something with it, but the former Master of Royal Music was not even sure how the thing was meant to be tuned.

As he sat pondering the lyre, several lamplight girls and women came out of the mist and joined the group.

"Aye, more news from the palace," one of them told the streetlord as he hailed them. "Seems that the music master may be livin'."

"What's yer meanin'?" asked the streetlord.

"I 'eard it from a militiaman, what 'eard it from a guard. The dead man were skinny, like, but a chambermaid the master 'ad rogered said she'd noticed that 'e were definitely fat. Seems the master let a warrior in to do the killing."

"Makes sense. Court fopsie like that would lose a duel 'gainst a roast chicken," said the streetlord.

Chambermaid? wondered Wallas. Must have been after that terrible night at the Musicians' Guild banquet.

"She expected a reward, yet they beheaded 'er for just knowin' 'im."

Wallas stayed silent as they laughed. What they were saying was largely true. He knew that one grasped a fighting ax by the end without the sharp metal bit, and he owned several ceremonial axes, but he had never actually swung one in anger--or even in training, if it came to that. As for crossbows, he had not so much as picked one up since the day he was born. Horses and riding? Horses were a long way up, and a lot more unsteady than a carriage. Wallas was definitely no warrior.

"Breffas, squire?" asked the former herbalist, holding up an oblong of charred meat by its tail.

"What is it?" asked Wallas, accepting the offering for fear of not fitting in.

"Roast battered rat."

"I see no batter."

"Nay, it's rat wot's been battered to death, then roasted."

Wallas gingerly removed a little meat with his teeth, smiled and nodded at the old man, then spat it out as soon as he turned away. His parents were dead. The thought took a while to make an impression on Wallas. In his time at court he had tried to live them down, because they were mere merchants. His father had actually been a pastry cook, and his mother distributed the produce. That made them technically merchants, rather than artisan-class. More or less. Actually from a strictly legal point of view his father was an artisan, while his mother was an artisan's wife. On the other hand, she did sell his loaves, buns, and pastries to five shops, making her a type of merchant. Now they were both dead, and because of him. More or less. I try to rouse grief within myself, but grief is apparently still in bed, he thought as he nibbled absently at his battered rat again. The odds on his own head being mounted on a pike and joining those of his parents above some gate were strengthening by the hour.

"Five hundred gold crowns is the reward for 'is 'ead, attached or otherwise," one of the lamplight women announced.

Wallas shivered with fear. Five hundred gold crowns was more than three generations of millers could earn in their combined lifetimes. He knew all about millers, because his father had employed one after he had become more prosperous. Wallas left the bridge, taking the empty wineskin with him. Through his father's associates he knew that wineskins were worth two copper demis.

By noon Wallas had indeed sold his wineskin for two copper demis, and exchanged one for a loaf of bread and a cut of cheese. He had eaten while watching his effigy being shot full of arrows and pelted with rotten fruit and vegetables. It was then burned at the stake. He tossed a stone at his burning straw form for the sake of blending in with the crowd. One of the militiamen who had brought the effigy and brushwood to the marketplace got up on the back of a cart and rang a bell for attention.

"Hark one and hark all!" he shouted. "Be it known here and throughout the city that this very afternoon there will be a gathering of bards within the palace grounds. At this gathering there will be free beer for one and all, and without limit."

The militiaman paused until the cheering and shouting died down. The vendors of assorted used musical instruments would soon be doing uncommonly good business, but the court-wise Wallas had already guessed the agenda. He had his lyre hidden under his stained and ragged cloak, and was already edging away.

"At the end of the afternoon, Prince Stavez will bestow a prize for the best loyal toast to the dead emperor, in verse."

It was all too clear to Wallas. Someone had collated the accounts of all the palace guards who had been on duty the night before. That someone soon realized that only minutes after the assassin had been killed, a bard had been discovered within mere yards of the exit to the secret escape route from the Master of Royal Music's bedchamber. The master was thus known to be alive, and to be hiding in the guise of a bard. There could be only one reason for the prince to stage a gathering of bards, and Wallas was fairly sure that everyone was liable to get a very unpleasant prize.

* * *

As far as stormy nights went, Alberin was hard to beat. Near-freezing rain lashed the port city, driven along by winds from the chill heart of the continent of Scalticar. Alberin was so often in the path of bad weather that the streets were all fringed with awnings, covered walkways, overhangs, and public shelters. Keeping loiterers out of small, dark alleyways was easy: the alleyways were merely left open to the sky, and the rain kept them free of shadowy figures with suspicious intentions.

The three shadowy figures of suspicious intent who were on the streets on the fortieth day of Threemonth, 3141, were not loitering, however. They were purposefully scanning what was visible of those streets by the light of one of the very few public lanterns that were still burning. So far their quarry had proved elusive, but they persisted with the patience of professionals. The lamplight girl that they now approached was distinguishable from the trio only by her strident perfume. The main occupational hazard for streetwalkers in Alberin was pneumonia, so that when they disported themselves in public they were even more heavily robed than members of some celibate religious orders on other continents. The girl turned as the men splashed over to her. They surrounded her. One held up a sack and a length of cord. Another waved a cudgel. The third offered, five silver coins on the palm of his hand.

"You have to be joking!" she exclaimed, not quite laughing.

"No joke," said the man with the silver coins. "Can you help?"

"Add another silver one to those in your palm, and you can have an experienced sailor with a Carpenters' Guild plate."

"Oh aye, and which house do we have to break into, and how many guards do we have to fight our way past?"

"None."

"None?"

"Well?"

"If he's what you say he is, three down and three on pickup."

A pale hand emerged from the folds of the girl's clothing, accepted three chilly silver coins, and withdrew again. She sauntered off, and the three men followed. Around a corner and halfway down the next street she stopped at a doorway, where what appeared to be a pile of dark, sodden rags lay in one corner. The press-gang's leader hunkered down.

"Gah! Peed his trousers!" he exclaimed.

"Not so," said the girl, nudging a piece of broken crockery with the toe of her shoe, then pointing to the shutter above the door. "I saw it all. He bunked down in the doorway, then got out his fife and started playing. The madam of the house emptied a chamber pot over him, then dropped the pot on his head when he didn't go away."

The press-gang's leader fingered a lump on the unconscious man's head, then looked up at a window. "Good shot. Aye, and there's a guild plate on the chain around his neck. Hammer shape, he's a carpenter all right. You say he's a sailor too?"

"I heard him playin' a river-barge jig before the pot hit him," replied the girl.

"A riverman, the only kind left, I suppose. Very well, me boys, truss him up and get him into the sack." He dropped two coins into the girl's outstretched hand. "I ought to deduct one for the smell."

"Skinny bugger, too," said the man with the rope.

"It comes out of your fee for the next one," the girl pointed out. "Could you have found him by yourselves?"

Another coin dropped into her hand. The largest of the men heaved the sack onto his shoulder.

"Don' tell Mother," mumbled the youth from within the sack, without really waking up.

"His name's Andry," the girl remarked.

"D'ye know him, then?" asked the leader.

"Not so, I got standards!" said the girl indignantly. "I heard the madam shouting 'Piss off!' and he shouted 'Andry Tennoner pisses off for nobody!'"

"True? Well, that saves them flogging it out of him later. Are ye calling it an early night, then?"

"Nay, I'm for a tavern and a mulled wine first. Who's he for?"

"The Stormbird."

"Oh aye, the last big coaster? Is she bound south again?"

"Nay. This is a special, a charter voyage to Palion, in the Sargolan Empire."

"Palion!" the girl exclaimed.

"Aye."

"Palion, as in across the Strait of Dismay?"

"Aye."

"But, but, you might as well set the ship afire and drown the crew at the end of the pier. Drooling Gerric was aboard the last ship to cross the Strait of Dismay. He's the one who drinks his ale under a table in the Lost Anchor, and crawls about on all fours."

"And that ship was the Stormbird," said the press-gang leader, with the calm of one who was not to be going on the voyage. "The cargo made everyone aboard rich."

"Oh aye, and the voyage left Gerric raving mad."

The press-gang moved off, reached the end of the covered walkway, and walked straight out into the rain and darkness. The girl stood looking after them, a hand to her mouth.

"He seemed a nice young fella, even if he were a slobby drunk," she said softly and with genuine remorse. "Like, I never knew..."

The crashing of unseen waves thundered from the direction of the harbor, foretelling what was sure to be Andry Tennoner's fate.

* * *

The megaliths of ringstone circles and other magical places often stand undisturbed for thousands of years, but all of them begin their existence as work that pays money to masons. In societies where money has not yet been invented, the payment might be a number of sheep, fish, or chickens in proportion to the size of the megalith, but there is always payment. Golgravor's Significant Stones never accepted any work from charities, least of all religious charities, but although the yard's current commission was definitely religious, it was paying large amounts of real money.

Golgravor Lassen's commission stated that seventeen megaliths were to be made, and the overall dimensions and design were specified quite precisely. Decoration was optional. Golgravor was particularly fond of the Grattorial school of floral embroidery of the twenty-seventh century, and he had directed his apprentices and assistants to cover every square inch of the stone megaliths in his workyard with entwined and flowering primroses, and bluebell vines.

"Not the seat area, however," Golgravor explained to a new freelance mason who was having his first tour of the workyard. "The dimensions of the seat area are absolutely precise, and are to be plain, unadorned rock."

"Looks to me like a man would recline with his arms held open above his head," replied Costerpetros.

"That is the general shape of it, yes."

"So, this is intended for some temple, to hold some priest in a position of prayer?"

"I cannot say. What I can say is that I'm paid in plain gold bars, and the gold is of a very high grade of purity."

"Oh. Well, er, who takes delivery of the stones?"

"The stones vanish, and someone drops a bar of gold payment where they stood."

"Just like that?"

"Yes."

"About ten tons of rock?"

"Five tons, actually. There's a bit hollowed out in the base, like it's going to sit on a rounded surface."

"And gold is left behind?"

"A bar of the very purest of gold."

"What does your client look like? Surely someone has seen him?"

"No, not a one. We were told never to spy on the collection. At dusk everyone withdraws, and at dawn we return. The megalith is gone, and there is one gold bar in its place."

"How many have you been commissioned to carve?"

"Seventeen, at five tons each. Now to work. That one goes out tonight, and there's one more to go after that. You're to work on number seventeen, doing the primrose decorations. It must be finished by the end of this week, and we've been falling behind schedule. That's why you've been hired. There's a big bonus if we finish on time."

"But who are the buyers? Don't you have any clue?"

"No. Be they people, dragons, spirits, or gods, they pay in large bars of pure gold. That's all we need to know, and that's all I want to know."

* * *

Costerpetros made sure that he was in place before dusk. He had worked hard for a week, even doing double shifts, and he had proved to be a popular recruit. He told good jokes, always shared his jar of wine, and was particularly interested in what even the most boring of artisans and apprentices had to say about the routines of the yard. At one stage he even ran a competition to see who could come up with the best theory of how the completed megaliths were being carried away, and by whom. Everyone pooled their knowledge and gossip, and the winner's theory was that a god reached down out of the clouds and took the megaliths away to be pieces in some enormous board game.

Now Costerpetros was lying flat-out in the long grass, with a green cloak draped over himself. The bar of gold that would pay for the megalith was reputed to weigh one hundred pounds. Costerpetros had a heavy-duty sling sewn with pack straps to carry the bar. A hundred pounds would be a strain, but he was strong. There would be a walk of a mile through woodland to where his brother was waiting with a horse and cart. Costerpetros knew he could manage that. He had even practiced walking that distance with twice the weight, for he left nothing to chance. On his feet was a pair of great taloned bird's feet, half a yard in length. They were made from leather, with claws of ivory, and would leave quite alarming impressions in the circle of white sand where the megalith had been left.

The megalith was on a wooden pallet, securely tied down, and with four thick ropes running from the edges and woven into a loop of braids that could support ten times the weight. It had been lifted from the working platform by a wooden pulley crane, and placed at the center of a circle of pure white sand that had been raked and brushed smooth.

The light faded in the west, and the sky was lit by two moonworlds and the stars. After all the chipping, hammering, cursing, work shanteys, and foremen's shouts of the daylight hours, the workyard now had a quite unsettling quality. By day it had been bright, hot, and noisy, but now it was dark, cool, and silent. Costerpetros lay absolutely still, apart from his breathing. Something would come by, something would appear. He thought about all the theories that had been suggested by his workmates. Perhaps a rent really would appear in the air above the megalith, and a huge, taloned hand would descend, draw the megalith up, then leave a gold bar. Daemons could open holes in the air itself; his brother had studied the magical arts to the seventh level of initiation, and he knew those things. Daemons also had good hearing, however, so it was important not to cry out with astonishment or fear if one appeared.

There was a swish in the darkness, and something briefly eclipsed the stars and moonworlds. Great wings beat above the workspace; then a shape like an enormous bat descended slowly and straddled the megalith. A daemon, not a god, thought Costerpetros. The thing's wings had a span greater than the workyard was wide, and its eyes glowed a faint bluish violet. There was a very large hook in its jaws, and from this hook a rope ran up into the sky. The daemon neatly attached the hook to the loop of rope--and Costerpetros saw no more. Neither did his brother, because another vast, winged shape swooped over the part of the woods where he sat waiting in his cart, spat a streamer of white-hot fire, then ascended back into the night sky.

* * *

Golgravor Lassen looked down at the body in the long grass, his hands on his hips and his head shaking. The hundred-pound gold bar had obviously been dropped from a great height, as it had obliterated the man's head. There was a lot of mess splattered about, but he had clearly been taken by surprise, because there was no sign of a struggle. A dark green cloak covered most of the body, but two large, clawed feet protruded. Golgravor lifted the cloak and determined that the body was that of a man. A search of the clothing produced a seal and guild scroll identifying him as Costerpetros. At this point a foreman came running over from the direction of the burned-out woodland.

"We found some metal fittings and powdery bits of bone that might have once been a cart, horse, and driver," he called.

"And I think I've found an accomplice," replied Golgravor, indicating the body.

The foreman took in the body, the bird feet, and the gold bar. He thought long and hard before trying to reply.

"When I was a lad, my mother said that if I did not finish all my dinner, then Chicken God would come and peck my gronnic off for wasting the flesh of his worshipers. I used to think it was just a story, but now..."

"According to the scroll in his pouch, this was Costerpetros, the new contract mason. Or maybe Costerpetros is really Chicken God in disguise."

The foreman tugged at a clawed foot. It came away. He let out a loud sigh of relief.

"I cannot tell you how cheered I am that the feet are false," he declared.

Golgravor waved a hand over the gold bar.

"Have a couple of apprentices collect it in a tool cart, then wash the blood and brains off."

"And the body?"

"Have it scraped up and disposed of after the constables see it."

The foreman tossed the false bird foot onto the body. "What are we to tell the men?" he asked.

They stood in silence for a moment, contemplating the body.

"The gold bar looks to have been dropped a full mile, from the way his head's splashed," said Golgravor. "The cart appears to have been turned to ash by something that can breathe fire as hot as the inside of a forge, and the megaliths are being lifted into the air when they are removed. All that points to very large things that can fly and breathe fire--and are very bad-tempered about being spied upon."

"Dragons?"

"Dragons don't exist."

"Then what?"

"Very large and rich birds wearing dragon costumes."

"Birds can't breathe fire."

"Then we are definitely narrowing the field to dragons."

"But you said dragons don't exist."

"Of course not, but if they did exist and they learned that you knew they existed, they might drop a gold bar on your head, too."

"So why do the dragons that don't exist want five-ton megaliths?"

"I neither know nor care."

"Er, you have not yet told me what we tell the men."

"Tell them that spying on our customers is a very dangerous idea, and show them the proof. Now get people moving! We've already wasted enough time this morning."

* * *

The fact that the Stormbird arrived at all was an occasion for wonder in Palion. The maze of shoals and rocks that lay across the approach to the harbor was now acting as a natural breakwater to mountainous waves raised by the latest Torean Storm, and no pilot had been willing to row out to the ship and guide it in. This proved to be no problem for the Stormbird, however. A particularly large wave had caught the ship, lifted it high, then flung it safely over the rocks in a seething, thundering maelstrom of foam. Within the harbor the waves were a mere five feet or so in height, and those of the crew who were capable of movement had no trouble guiding the ship past the inner breakwater and to the wharf.

It was now that a few dockers braved the screaming wind and stinging rain to help the crew tie up. What was left of the embarkation flag declared the ship to be from Alberin on the continent of Scalticar, a mere four hundred miles to the south. Normally the voyage would have taken little more than a week, but this crossing had been dragged out to thirty-two days by a continuous storm. Cold, hard rain was lashing the city, driven by a wind that howled like a mortally wounded dragon.

A gangplank was brought up and its grapples dropped onto the side of the ship. An ashen-faced, haggard woman of about thirty appeared and shuffled cautiously down to the wharf. She had a large sling bag over her shoulder, and her robes were soaked with water that had burst over the ship as it was carried over the rocks. Having stepped off the gangplank, she dropped to her knees and began to kiss the wet timbers of the pier. The rain beat down without mercy, and the wind flung spray, rain, and occasional hailstones at her.

A heavily robed official hurried along the pier, stopped, and extended a hand to the woman.

"Welcome to Palion, gateway to the tropics," he said as he helped her to her feet. "Are you willing to make a declaration before whatever gods you worship that you are not under sentence for any civil or felonious crime within the Empire of Sargol or its allies, or do you carry goods in excess of the value of five gold crowns?"

The woman reached into her robes, fished about for a moment, then drew out a gold crown. She pressed it into the official's hand.

"No," she croaked, with the energy of someone who has been vomiting almost continuously for thirty-two days.

"Ah, I see," responded the official, holding out a small scroll. "Just write your name at the bottom of that at your leisure. Bear in mind that it's from a batch declared stolen, so try to stay out of trouble. Any other passengers aboard the ship?"

"None that can move."

"Ah good, I'll pay them a visit right away."

As the official hurried aboard the ship, the woman began walking unsteadily down the pier. A youth now hurried down the steps of the wharf wall and ran out onto the pier.

"Learned Elder?" he ventured. "Learned Elder Terikel of the Metrologons?"

The woman looked up and focused her red-rimmed, bloodshot eyes on the youth.

"Yes," she wheezed.

"Learned Rector Feodorean sent me to greet you," he explained. "She regrets that she cannot be here in her personal persona, so to speak, ha ha."

The attempt at a joke was either ignored, misunderstood as bad grammar, or missed completely.

"Not nearly so much as I regret having made the voyage to be here in person," rasped the Elder.

"The emperor was assassinated recently, so Rector Feodorean's services are required at court."

"Lucky emperor," muttered the Elder.

"My lady!" exclaimed the youth. "Our emperor's death is not to be made light of."

"Young man, for over thirty days I would cheerfully have died to escape the waves, wind, spray, damp, tossing, pitching, rolling, vomiting, and cries of 'Pump, ye buggers, pump!' Even now I am not sure why I did not kill myself on the first day out."

"But that is all part of life at sea, my lady. Why, I have been to sea as well--"

"And was your ship ever airborne, due to the severity of the waves and wind?" rasped Terikel.

The youth gulped. "Surely not," he managed.

"Surely so. I lost count after our tenth flight." She stopped and leaned against a bollard, comforting herself with its solidity. "I never believed in love at first sight until I saw the timbers of this pier."

"But why did you leave Scalticar?"

"For a start, to see your mistress. What is your name?"

"Oh! My most abject apologies for not introducing myself. The shock of seeing your distress rendered me--"

"What is your name?" Terikel insisted.

"Brynar, Brynar! Brynar Bulsaros, acting head prefect of the Palion Academy of Aetheric Arts. We call it the A-three when--"

"I know, I know, the A-three when you are trying to impress tavern wenches, the Arrr when you are drunk, and the Aaah when you are falling asleep in boring lectures. Now take me to the academy's bathhouse, and kindly carry my pack. While I am cleaning up, you are going to burn my clothes."

"Burn them, my lady?" gasped Brynar.

"By the time even a diligent washerwoman gets the stench of vomit out of them, I am liable to be dead from old age. Check my pack, I have a change of clothing sealed in wax paper and leather."

Behind them, on the deck of the Stormbird, the official waved his arms crosswise three times. One for examine her disembarcation scroll, two for arrest her, and three for confiscate whatever she is carrying.

Copyright © 2004 by Sean McMullen

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details