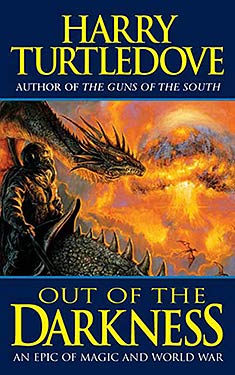

Out of the Darkness

| Author: | Harry Turtledove |

| Publisher: |

Pocket Books, 2005 Tor, 2004 |

| Series: | Darkness: Book 6 |

|

1. Into the Darkness |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Harry Turtledove's rousing saga of a fantastic world at war, which began in Into the Darkness and continued through Darkness Descending, Through the Darkness, Rulers of the Darkness, and Jaws of Darkness, draws to its climactic conclusion in Out of the Darkness.

As the Derlavaian War rages into its last and greatest battles, allied nations maneuver for positions against each other in a postwar world. But before that time can come, the forces of Algarve, Unkerlant, and their allies must clash a final time, countering army with army and battle magic with ever-more-powerful battle magic. In the midst of it all, the people the war has battered and reshaped must struggle to face their greatest individual challenges, as loves are shattered and found, terrible crimes avenged... and some journeys end forever.

And the end of the war may not bring peace...

Excerpt

One

Ealstan intended to kill an Algarvian officer. Had the young Forthwegian not been fussy about which redhead he killed, or had he not cared whether he lived or died in the doing, he would have had an easier time of it. But, with a wife and daughter to think about, he wanted to get away with it if he could. He'd even promised Vanai he wouldn't do anything foolish. He regretted that promise now, but he'd always been honorable to the point of stubbornness, so he still felt himself bound by it.

And he wanted to rid the world of one of Mezentio's men in particular. Oh, he would have been delighted to see all of them dead, but he especially wanted to be the means by which this one died. Considering what the whoreson did to Vanai, and made her do for him, who could blame me?

But, like a lot of rhetorical questions, that one had an obvious, unrhetorical answer: all the other Algarvians in Eoforwic. The Algarvians ruled the capital of Forthweg with a mailed fist these days. Ealstan had been part of the uprising that almost threw them out of Eoforwic. As in most things, though, almost wasn't good enough; he counted himself lucky to remain among the living.

Saxburh smiled and gurgled at him from her cradle as he walked by. The baby seemed proud of cutting a new tooth. Ealstan was glad she'd finally done it, too. She'd been fussy and noisy for several nights before it broke through. Ealstan yawned; he and Vanai had lost sleep because of that.

His wife was in the kitchen, building up the fire to boil barley for porridge. "I'm off," Ealstan said. "No work for a bookkeeper in Eoforwic these days, but plenty for someone with a strong back."

Vanai gave him a knotted cloth. "Here's cheese and olives and an onion," she said. "I only wish it were more."

"It'll do," he said. "I'm not starving." He told the truth. He was hungry, but everyone in Eoforwic except some--not all--of the Algarvians was hungry these days. He still had his strength. To do a laborer's work, he needed it, too. Wagging a finger at her, he added, "Make sure you've got enough for yourself. You're nursing the baby."

"Don't worry about me," Vanai said. "I'll do fine, and so will Saxburh." She leaned toward him to kiss him goodbye.

As their lips brushed, her face changed--literally. Her eyes went from brown to blue-gray, her skin from swarthy to pale, her nose from proud and hooked to short and straight. Her hair stayed dark, but that was because it was dyed--he could see the golden roots, which he hadn't been able to do a moment before. She seemed suddenly taller and slimmer, too: not stubby and broad-shouldered like most Forthwegians, including Ealstan himself.

He finished the kiss. Nothing, as far as he was concerned, was more important than that. Then he said, "Your masking spell just slipped."

Her mouth twisted in annoyance. Then she shrugged. "I knew I was going to have to renew it pretty soon, anyhow. As long as it happens inside the flat, it's not so bad."

"Not bad at all," Ealstan said, and gave her another kiss. As she smiled, he went on, "I like the way you look just fine, regardless of whether you seem like a Forthwegian or a Kaunian. You know that."

Vanai nodded, but her smile slipped instead of getting bigger as he'd hoped. "Not many do," she said. "Most Forthwegians have no use for me, and the Algarvians would cut my throat to use my life energy against Unkerlant if they saw me the way I really am. I suppose there are other Kaunians here, but how would I know? If they want to stay alive, they have to stay hidden, the same as I do."

Ealstan remembered the golden roots he'd seen. "You should dye your hair again, too. It's growing out."

"Aye, I know. I'll take care of it," Vanai promised. One way the Algarvians checked to see whether someone was a sorcerously disguised Kaunian was by pulling out a few hairs and seeing if they turned yellow when removed from the suspect's scalp. Ordinary hair dye countered that. The Algarvians being who and what they were, thoroughness in such matters paid off; Vanai kept the hair between her legs dark, too.

Carrying his meager lunch, Ealstan went downstairs and out onto the street. The two blocks of flats across from his own were only piles of rubble these days. The Algarvians had smashed both of them during the Forthwegian uprising. Ealstan thanked the powers above that his own building had survived. It was, he knew, only luck.

A Forthwegian man in a threadbare knee-length tunic scrabbled through the wreckage across the street, looking for wood or whatever else he could find. He stared up in alarm at Ealstan, his mouth a wide circle of fright in the midst of his shaggy gray beard and mustache. Ealstan waved; like everyone else in Eoforwic, he'd spent his share of time guddling through ruins, too. The shaggy man relaxed and waved back.

Not a lot of people were on the streets: only a handful, compared to the days before the uprising and before the latest Unkerlanter advance stalled--or was allowed to stall?--in Eoforwic's suburbs on the west bank of the Twegen River. Ealstan cocked his head to one side. He didn't hear many eggs bursting. King Swemmel's soldiers, there on the far bank of the Twegen, were taking it easy on Eoforwic today.

His boots squelched in mud. Fall and winter were the rainy season in Eoforwic, as in the rest of Forthweg. At least I won't have to worry much about snow, the way the Unkerlanters would if they were back home, Ealstan thought.

He spotted a mushroom, pale against the dark dirt of another muddy patch, and stooped to pick it. Like all Forthwegians, like all the Kaunians in Forthweg--and emphatically unlike the Algarvian occupiers--he was wild for mushrooms of all sorts. He suddenly shook his head and straightened up. He was wild for mushrooms of almost all sorts. This one, though, could stay where it was. He knew a destroying power when he saw one. His father Hestan, back in Gromheort, had used direct and often painful methods to make sure he could tell a good mushroom from a poisonous one.

I wish the redheads liked mushrooms, he thought. Maybe one of them would pick that one and kill himself.

Algarvians directed Forthwegians hauling rubble to shore up the defenses against the Unkerlanter attack everyone in the city knew was coming. Forthwegian women in armbands of blue and white--Hilde's Helpers, they called themselves--brought food to the redheads, but not to their countrymen, who were working harder. Ealstan scowled at the women. They were the female equivalent of the men of Plegmund's Brigade: Forthwegians who fought for King Mezentio of Algarve. His cousin Sidroc fought in Plegmund's Brigade if he hadn't been killed yet. Ealstan hoped he had.

Instead of joining the Forthwegian laborers as he often did, Ealstan turned away toward the center of town. He hadn't been there for a while: not since he and a couple of other Forthwegians teamed up to assassinate an Algarvian official. They'd worn Algarvian uniforms to do it, and they'd been otherwise disguised, too.

Back then, the redheads had held only a slender corridor into the heart of Eoforwic--but enough, curse them, to use to bring in reinforcements. Now the whole city was theirs again... at least, until such time as the Unkerlanters chose to try to run them out. Ealstan had a demon of a time finding the particular abandoned building he was looking for. "It has to be around here somewhere," he muttered. But where? Eoforwic had taken quite a pounding since he'd last come to these parts.

If this doesn't work, I'll think of something else, he told himself. Still, this had to be his best chance. There was the building: farther into Eoforwic than he'd recalled. It didn't look much worse than it had when he and his pals ducked into it to change from Algarvian tunics and kilts to Forthwegian-style long tunics. Ealstan ducked inside. The next obvious question was whether anyone had stolen the uniforms he and his comrades had abandoned.

Why would anybody? he wondered. Forthwegians didn't, wouldn't, wear kilts, any more than their Unkerlanter cousins would. Ealstan didn't think anybody could get much for selling the clothes. And so, with a little luck...

He felt like shouting when he saw the uniforms still lying where they'd been thrown when he and his friends got rid of them. He picked up the one he'd worn. It was muddier and grimier than it had been: rain and dirt and dust had had their way with it. But a lot of Algarvians in Eoforwic these days wore uniforms that had known better years. Ealstan held it up and nodded. He could get away with it.

He pulled his own tunic off over his head, then got into the Algarvian clothes. The high, tight collar was as uncomfortable as he remembered. His tunic went into the pack. He took from his belt pouch first a small stick, then a length of dark brown yarn and another of red. He twisted them together and began a chant in classical Kaunian. His spell that would temporarily disguise him as an Algarvian was modeled after the one Vanai had created to let her--and other Kaunians--look like the Forthwegian majority and keep Mezentio's men from seizing them.

When Ealstan looked at himself, he could see no change. Even a mirror wouldn't have helped. That was the sorcery's drawback. Only someone else could tell you if it had worked--and you found out the hard way if it wore off at the wrong time. He plucked at his beard. It was shaggier than Algarvians usually wore theirs. They often went in for side whiskers and imperials and waxed mustachios. But a lot of them were more unkempt than they had been, too. He thought he could get by with the impersonation--provided the spell had worked.

Only one way to learn, he thought again. He strode out of the building. He hadn't gone more than half a block before two Algarvian troopers walked by. They both saluted. One said, "Good morning, Lieutenant." Ealstan returned the salute without answering. He spoke some Algarvian, but with a sonorous Forthwegian accent.

He shrugged--then shrugged again, turning it into a production, as Algarvians were wont to do with any gesture. He'd passed the test. Now he had several hours in which to hunt down that son of a whore of a Spinello. The stick he carried was more likely to be a robber's weapon than a constable's or an officer's, but that didn't matter so much these days, either. If a stick blazed, Mezentio's men would use it.

Algarvian soldiers saluted him. He saluted officers. Forthwegians gave him sullen looks. No one paid much attention to him. He hurried west toward the riverfront, looking like a man on important business. And so he was: that was where he'd seen Spinello. He could lure the redhead away, blaze him, and then use a counterspell to turn back into his proper self in moments.

He could... if he could find Spinello. The fellow stood out in a crowd. He was a bantam rooster of a man, always crowing, always bragging. But he wasn't where Ealstan had hoped and expected him to be. Had the Unkerlanters killed him? How would I ever know? Ealstan thought. I want to make sure he's dead. And who has a better right to kill him than I do?

"Where's the old man?" one redheaded footsoldier asked another.

"Colonel Spinello?" the other soldier returned. The first man nodded. Ealstan pricked up his ears. The second Algarvian said, "He went over to one of the officers' brothels by the palace, the lucky bastard. Said he had a meeting somewhere later on, so he might as well have some fun first. If it's anything important, you could hunt him up, I bet."

"Nah." The first redhead made a dismissive gesture. "He asked me to let him know how my sister was doing--she got hurt when those stinking Kuusamans dropped eggs on Trapani. My father writes that she'll pull through. I'll tell him when I see him, that's all."

"That's good," the second soldier said. "Glad to hear it."

Ealstan turned away in frustration. He wouldn't get Spinello today. Braving an Algarvian officers' brothel was beyond him, even if murder wasn't. He also found himself surprised to learn Spinello cared about his men and their families. But then he thought, Well, why shouldn't he? It's not as if they were Kaunians.

...

For four years and more, the west wing of the mansion on the outskirts of Priekule had housed the Algarvians who administered the capital of Valmiera for the redheaded conquerors. No more. Occupying it these days were Marquis Skarnu; his fiancee, Merkela; and Gedominu, their son, who was just starting to pull himself upright.

Skarnu's sister, Marchioness Krasta, still lived in the east wing, as she had all through the occupation. She'd had an Algarvian colonel warming her bed all through the occupation, too, but she loudly insisted the baby she was carrying belonged to Viscount Valnu, who'd been an underground leader. Valnu didn't disagree with her, either, worse luck. That kept Skarnu from throwing Krasta out of the mansion on her shapely backside.

He had to content himself with seeing his sister as little as he could. A couple of times, he'd also had to keep Merkela from marching into the east wing and wringing Krasta's neck. The Algarvians had taken Merkela's first husband hostage and blazed him; she hated collaborators even more than redheads.

"We don't know everything," Skarnu said, not for the first time.

"We know enough," Merkela answered with peasant directness. "All right, so she slept with Valnu, too. But she let the redhead futter her for as long as he was here. She has to pay the price."

"No one ever said she didn't. No one ever said she won't." While Skarnu was out in the provinces, he'd got used to thinking of himself as being without a sister after he'd learned that Krasta was keeping company with her Algarvian colonel. Finding things weren't quite so simple jolted him, too. He sighed and added, "We're not quite sure what the price should be, that's all."

"I'm sure." But Merkela grimaced and turned away. She didn't sound sure, not even to herself. Doing her best to recover the fierceness she'd had when fighting Algarve seemed futile, she brushed blond hair back from her face and said, "She deserves worse than this. This is nothing."

"We can't be too hard on her, not when we don't know for certain whose baby it is," Skarnu said. They'd had that argument before, too.

Before they could get deeply into it again, someone knocked on the door to their bedchamber. Skarnu went to open it with more than a little relief. The butler, Valmiru, bowed to him. "Your Excellency, a gentleman from the palace to see you and your, ah, companion." He wasn't used to having Merkela in the mansion, not anywhere close to it, and treated her as he might have treated any other dangerous wild animal.

Her blue eyes widened now. "From the palace?" she breathed. Gentlemen from the palace were not in the habit of calling on farms outside the hamlet of Pavilosta.

"Indeed," Valmiru said. His eyes were blue, too, like those of Merkela, of Skarnu, and of almost all folk of Kaunian blood, but a blue frosty rather than fiery. Over the years, his hair had faded almost imperceptibly from Kaunian blond toward white.

Merkela pushed at Skarnu. "Go see what the fellow wants."

"I know one thing he wants," Skarnu said. "He wants to see both of us." When Merkela hung back, he took her hand, adding, "You weren't afraid to face the redheads when they were blazing at you. Come on." Merkela glanced toward Gedominu, but the baby offered her no excuse to hang back: he lay asleep in his cradle. Rolling her eyes up to the ceiling like a frightened unicorn, she went with Skarnu.

"Good day, your Excellency, milady." The man from the royal palace bowed first to Skarnu and then, just as deeply, to Merkela. He was handsome and dapper, his tunic and trousers too tight to be quite practical. Skarnu had outfits like that, but he'd come to appreciate comfort in his own time on a farm. Merkela's tunics and trousers were all of the practical sort needed if one were to do actual work in them. Instead of working, the functionary handed Skarnu a sealed envelope, then bowed again.

"What have we here?" Skarnu murmured, and opened it. Someone who practiced elegant calligraphy instead of working had written, To the Marquis Skarnu and the Lady Merkela: the pleasure of your company is requested by his Majesty, King Gainibu of Valmiera, at a reception this evening to honor those who upheld Valmieran courage during the dark days of occupation.

"I trust you will come?" the palace functionary said.

Skarnu nodded, but Merkela asked a question that sounded all the sharper for being so nervous: "Is Krasta invited?" She gave Skarnu's sister no title whatever.

Voice bland, the functionary replied, "This is the only invitation I was charged to bring here." Valmiru sighed when he heard that. All the servants would hear it in short order. So would Krasta, and that was liable to be ugly.

But Merkela nodded as sharply as if her family had been noble for ten generations. "Then we'll be there," she declared. The functionary bowed and departed. Only after the butler had closed the door behind him did Merkela let out something that sounded very much like a wail: "But what am I going to wear?"

"Go out. Go shopping," Skarnu said--even he, a mere man, could see why she might be worried.

But he couldn't guess how worried she was. In something like despair, Merkela cried, "But how do I know what people wear to the palace? I don't want to look like a fool, and I don't want to look like a whore, either."

Valmiru coughed to draw her notice, then said, "You might do well to take someone who is knowledgeable in such matters with you--Bauska, perhaps."

"Bauska?" Merkela exclaimed. "With her half-Algarvian bastard?"

"She's Krasta's maidservant," Skarnu said. "She knows clothes better than anyone else here."

"She knows what I think of her, too," Merkela said. "She'd probably get me to buy something ugly just for spite."

"Whatever she suggests, bring it back and try it on for me first," Skarnu said. "I know enough not to let that happen. But Bauska's the best person you could choose...unless you wanted to go out with Krasta?" As he'd thought it would, that made Merkela violently shake her head. It also persuaded her to go out with the maidservant. Skarnu hadn't been so sure that would happen.

Gedominu woke up while his mother was on her expedition to Priekule. Proving he'd been away from his servants for a long time, Skarnu changed him himself and fed him little bits of bread. The baby hummed happily while he ate. Skarnu wished he himself were so easy to amuse.

A peremptory knock on the door warned him he was about to be anything but amused. He thought about ignoring it, but that wouldn't do. Sure enough, Krasta stood in the hallway. Without preamble, she said, "What's this I hear about you and...that woman going to the palace tonight?"

"It's true," Skarnu answered. "His Majesty invited both of us."

"Why didn't he invite me?" his sister demanded. Both her voice and the line of her jaw seemed particularly hard and unyielding.

"I have no idea," Skarnu said. "Why don't you ask him the next time you see him?" And then, his own temper boiling over, he asked, "Will he recognize you if you're not on an Algarvian's arm?"

"Futter you," Krasta said crisply. She turned and stalked away. Skarnu resisted the impulse to give her a good boot in the rear to speed her passage. She is pregnant, he reminded himself.

"Dada!" Gedominu said, and Skarnu's grim mood lightened. His son made him remember what was really important.

When Merkela returned festooned with boxes and packages, he waited to see what she'd bought, then clapped his hands together. The turquoise tunic and black trousers set off her eyes, emphasized her shape without going too far, and made the most of her suntanned skin. "You're beautiful," Skarnu said. "I've known it for years. Now everyone else will, too."

Despite her tan, she turned red. "Nonsense," she said, or a coarse, back-country phrase that meant the same thing. "Everyone at the court will sneer at me." Skarnu answered with the same coarse phrase. Merkela blinked and then laughed.

On the way to the palace, she snarled whenever she saw a woman shaved bald or with hair growing out after a shaving: the mark of many who'd collaborated horizontally. "I wonder if Viscount Valnu will have his hair shaved, too," Skarnu remarked.

Merkela gave him a scandalized look. "Whatever he did, he did for the kingdom."

"I know Valnu," Skarnu told her. "He may have done it for the kingdom, but that doesn't mean he didn't enjoy every minute of it." Merkela clucked but didn't answer.

When they pulled up in front of the palace, Skarnu handed Merkela down, though he knew she was used to descending for herself. The driver took out a flask with which to keep himself warm. A flunky checked Skarnu and Merkela's names off a list. "Go down this corridor," the fellow said, pointing. "The reception will be in the Grand Hall."

"The Grand Hall," Merkela murmured. Her eyes were already enormous. They got bigger with every step she took along the splendid corridor. "This is like something out of a romance, or a fairy tale."

"It's real enough. It's where King Gainibu declared war on Algarve," Skarnu said. "I didn't see him do it; I'd already been called to my regiment. But the kingdom didn't live happily ever after, I'll tell you that."

At the entry to the Grand Hall, another flunky in a fancy uniform called out, "Marquis Skarnu and the Lady Merkela!" Merkela turned red again. Skarnu watched her eyeing the women already in the Grand Hall. And, a moment later, he watched her back straighten as she realized she wasn't out of place after all as far as looks and clothes went.

Skarnu took her arm. "Come on," he said, and steered her toward the receiving line. "Time for the king to meet you." That flustered her anew. He added, "Remember, this is why he invited you."

Merkela nodded, but nervously. The line moved slowly, which gave her the chance to get back some of her composure. Even so, she squeezed Skarnu's hand and whispered, "I don't believe this is really happening."

Before Skarnu could answer, the two of them stood before the king. Gainibu had aged more than the years that lay between now and the last time Skarnu saw him; the red veins in his nose said he'd pickled as well as aged. But his grip was firm as he clasped Skarnu's hand, and he spoke clearly enough: "A pleasure, your Excellency. And your charming companion is--?"

"My fiancée, your Majesty," Skarnu answered. "Merkela of Pavilosta."

"Your Majesty," Merkela whispered. Her curtsy was awkward, but it served.

"A pleasure to meet you, milady," the king said, and raised her hand to his lips. "I've seen Skarnu's sister at enough of these functions, but she was always with that Colonel Lurcanio. Some things can't be helped. Still, this is better."

"Thank you, your Majesty," Merkela said. She had her spirit back now, and looked around the Grand Hall as if to challenge anyone to say she didn't belong there. No one did, of course, but anyone who tried would have been sorry.

Skarnu glanced back at Gainibu as he led Merkela away. Gainibu, plainly, had not had an easy time during the Algarvian occupation. Even so, he still remembered how to act like a king.

...

The dragon farm lay just outside a Yaninan village called Psinthos. Sleet blew into Count Sabrino's face as he trudged toward the farmhouse where he'd rest till it was time to take his wing into the air and throw the dragonfliers at the Unkerlanters yet again. Mostly, the mud squelched under his boots, but it also had a gritty crunch that hadn't been there a couple of days before.

It's starting to freeze up and get hard, Sabrino thought. That's not so good. It means better footing for behemoths, and that means King Swemmel's soldiers will come nosing forward again. Things have been pretty quiet down here the last couple of days. Nothing wrong with that. I like quiet.

He opened the door to the farmhouse, then slammed it and barred it to keep the wind from ripping it out of his hands. Then he built up the fire, feeding it wood one of the dragon-handlers had cut. The wood was damp, and smoked when it burned. Sabrino didn't much care. Maybe it'll smother me, went through his mind. Who would care if it did? My wife might, a little. My mistress? He snorted. His mistress had left him for a younger man, only to discover the other fellow wasn't so inclined to support her in the luxury to which she'd been accustomed.

Count Sabrino snorted again. I wish I could leave me for a younger man. He was nearer sixty than fifty; he'd fought as a footsoldier in the Six Years' War more than a generation before. He'd started flying dragons because he didn't want to get caught up once more in the great slaughters on the ground, of which he'd seen entirely too many in the last war. And so, in this war, he'd seen plenty of slaughters from the air. It was less of an improvement than he'd hoped.

Smoky or not, the fire was warm. Little by little, the chill began to leach out of Sabrino's bones. Heading into the fourth winter of the war against Unkerlant. He shook his head in slow wonder. Who would have imagined that, back in the days when Mezentio of Algarve hurtled his army west against Swemmel? One kick and the whole rotten structure of Unkerlant would come crashing down. That was what the Algarvians had thought then. They'd learned some hard lessons since.

Joints clicking, Sabrino got to his feet. I had a flask somewhere. He thumped his forehead with the heel of his hand. I really am getting old if I can't remember where. He snapped his fingers. "In the bedding--that's right," he said aloud, as if talking to himself weren't another sign of too many years.

When he found the flask, it felt lighter than it should have. Of that he had no doubt whatever. If that dragon-handler gives me wood, I don't suppose I can begrudge him a knock of spirits. He yanked out the stopper and poured down a knock himself. The spirits were Yaninan: anise-flavored and strong as a demon.

"Ah," Sabrino said. Fire spread outward from his belly. He nodded, slowly and deliberately. I'm going to live. I may even decide I want to.

At that, he was better off than a lot of Algarvian footsoldiers. Psinthos was far enough behind the line to be out of range of Unkerlanter egg-tossers. How long that would last with the ground freezing, he couldn't guess, but it remained true for the time being. And the furs and leather he wore to fly his dragon also helped keep him warm on the ground.

Someone knocked on the door. "Who's there?" Sabrino called.

The answer came in Algarvian, with a chuckle attached: "Well, it's not the king, not today."

King Mezentio had visited Sabrino, more than once. He wished the king hadn't. They didn't see eye to eye, and never would. That was the reason Sabrino, who'd started the war as a colonel and wing commander, had never once been promoted. He opened the door and held out the flask. "Hello, Orosio. Here, have some of this. It'll put hair on your chest."

"Thanks, sir," Captain Orosio said. "Don't mind if I do." The squadron commander drank while Sabrino shut the door. After drinking, Orosio made a horrible face. "Burn the hair off my chest, more likely. But still, better bad spirits than none at all." He took another swig.

"What can I do for you?" Sabrino asked.

"Feels like a freeze is coming," Orosio said as he walked over to stand in front of the fire. He was in his late thirties, almost as old for a captain as Sabrino was for a colonel. Part of that came from serving under Sabrino--a man under a cloud naturally put his subordinates under one, too. And part of it sprang from Orosio's own background: he'd had barely enough noble blood to make officer's rank, and not enough to get promoted.

But that didn't mean he was stupid, and it didn't mean he was wrong. "I thought the same thing myself, walking back here after we landed," Sabrino said. "If the ground firms up--and especially if the rivers start freezing over--the Unkerlanters will move."

"Aye," Orosio said. The single word hung in the air, a shadow of menace. Orosio turned so that he faced east, back toward Algarve. "We haven't got a lot of room left to play with, sir, not any more. Before long, Swemmel's bastards are going to crash right on into our kingdom."

"Unless we stop them and throw them back," Sabrino said.

"Aye, sir. Unless." Those words hung in the air, too. Orosio didn't believe it.

Sabrino sighed. He didn't blame his squadron commander. How could he, when he didn't believe it, either? The Derlavaian War was far and away the greatest fight the world had ever known--big enough to dwarf the Six Years' War, which the young Sabrino who'd served in the earlier struggle would never have imagined possible at the time--and Algarve, barring a miracle, or several miracles, looked to be on the losing end of it, just as she had before.

King Mezentio promised miracles: miracles of sorcery that would throw back not only the Unkerlanters but also the Kuusamans and Lagoans in the east. So far, Sabrino had seen only promises, not miracles. Mezentio couldn't even make peace; things being as they were, no one was willing to make peace with him.

What did, what could, a soldier trapped in a losing war do? Sabrino strode over and set a hand on Orosio's shoulder. "My dear fellow, we have to keep doing the best we can, for our own honor's sake if nothing else," he said. "What other choice have we? What else is there?"

Orosio nodded. "Nothing else, sir. I know that. It's only...There's not a lot of honor left to save any more, either, is there?"

After we started massacring Kaunians to gain the sorcerous energy we needed to beat Unkerlant? After we mixed modern sophisticated sorcery and ancient barbarism and still didn't get everything we wanted because Swemmel was willing to be every bit as savage as we were and an extra six inches besides? No wonder no one wants to make peace with us. I wouldn't, if I were our enemies.

But he couldn't tell Orosio that. He said what he could: "You know my views, Captain. You also know that no one of rank higher than mine pays the least attention to them. Let me have that flask again. If I drink enough, maybe I won't care."

He hadn't even raised it to his lips, though, when someone else knocked on the door. He opened it and discovered a crystallomancer shivering there. The mage said, "Sir, I just got word from the front. Unkerlanter artificers are trying to throw a bridge over the Skamandros River. If they do..."

"There'll be big trouble," Sabrino finished for him. The crystallomancer nodded. Sabrino asked, "Aren't there any dragons closer and less worn than this poor, miserable wing? We just came in from another mission, you know."

"Of course, sir," the crystallomancer said. "But no, sir, there aren't. You know how thin we're stretched these days."

"Don't I just?" Sabrino turned back to Orosio. "Do you think we can get them into the air again, Captain?"

"I suppose so, sir," the squadron commander answered. "Powers above help us if the Unkerlanters hit us with fresh beasts while we're in the air, though--or even the Yaninans."

"Or even the Yaninans," Sabrino echoed with a sour smile. Tsavellas' small kingdom lay between Algarve and Unkerlant. He'd taken Yanina into the Derlavaian War as Algarve's ally--not that Yaninan soldiers had covered themselves with glory on the austral continent or in Unkerlant. And, when Unkerlanter soldiers poured into Yanina, Tsavellas had switched sides with revoltingly good timing. With another sour smile, Sabrino went on, "As we said, we have to do what we can. Let's go do it."

His dragon-handler squawked in dismay when he reappeared. His dragon screamed in brainless fury--the only kind it had--when he took his place once more at the base of its long, scaly neck. More handlers brought a couple of eggs to fasten under its belly. It didn't claw at them, though Sabrino couldn't figure out why.

"Keep feeding it," he told the handler, who tossed the dragon chunks of meat covered with crushed brimstone and cinnabar to make it flame hotter and farther. Algarve was desperately short of cinnabar these days. Sabrino wondered what his kingdom would do when it ran out altogether. What will we do? We'll do without, that's what.

Before long, all twenty-one dragonfliers were aboard their mounts. The wing had a paper strength of sixty-four, and hadn't been anywhere close to it since the opening days of the war against Unkerlant. Stretched too thin, Sabrino thought again. He nodded to the handler, who undid the chain that held the dragon to an iron stake. Sabrino whacked the beast with an iron-tipped goad. With another scream of fury, the dragon sprang into the air, batwings thundering. The rest of the men he led followed, each dragon painted in a different pattern of Algarve's green, red, and white.

With low clouds overhead, the wing had to stay close to the ground if it wanted to find its target. You can't let Unkerlanters gain a bridgehead. Sabrino knew that as well as every other Algarvian officer. King Swemmel's men were too cursed good at bursting out of such abscesses in the front when they judged the time ripe.

Orosio's image appeared, tiny and perfect, in the crystal Sabrino carried. "There's the bridge, sir," he said. "On the bend of the river, a little north of us."

Sabrino turned his head to the right. "Aye, I see it," he said, and guided his dragon toward it. "The wing will follow me in the attack. With a little luck, the rain will weaken the beams from the Unkerlanters' heavy sticks." They would know the Algarvians had to wreck a bridge if they could, and they would want to stop Mezentio's men from doing it. That meant blazing dragons from the sky, if they could manage it.

As Sabrino guided his dragon into a dive toward the bridge snaking across the Skamandros, the Unkerlanters on the ground did start blazing at him. He was the lead man: he drew the beams. He could hear raindrops and sleet sizzling into steam as beams burned through them. When one passed close, he smelled a breath's worth of lightning in the air. Had it struck...But it missed.

Below him, the bridge swelled with startling speed. He released the eggs under his dragon's belly, then urged the beast higher into the air once more. He saw the flashes of sorcerous energy and heard the roars as the eggs burst behind him. More flashes and roars said his dragonfliers were striking the bridge, too.

He twisted in his harness, trying to see what had happened. He let out a whoop on spotting what was left of the bridge: three or four eggs had burst right on it. "You bastards will be a while fixing that!" he shouted, and turned his dragon back toward the farm in what passed for triumph these days. Only eighteen dragons landed with his. The bridge had cost the other two, and the men who flew them. It was, unquestionably, a victory. But how many more such "victories" could Algarve afford before she had no dragonfliers left?

...

Lieutenant Leudast stared glumly east across the Skamandros River. The river, running harder than usual because of the late-fall rains and not yet ready to freeze over, had stalled Unkerlant's armies longer than its commanders would have wanted. Artificers were supposed to have bridged it by now, but Algarvian dragons had put paid to that. Now the artificers, or those of them the attack from the air hadn't killed, were trying again.

Captain Drogden came up to Leudast. Drogden was a rugged forty; like Leudast himself, he'd seen a lot of war. He headed the regiment of which Leudast commanded a company. Both of them wore hooded capes over their tunics, and both of them had the hoods up to fight the freezing rain. Both of them also wore wool leggings, wool drawers, and stout felt boots. Cold was one thing Unkerlanter warriors knew how to beat.

"Maybe we'll get it across this time," Drogden said, peering through the nasty rain at the artificers at work.

"Maybe." Leudast didn't sound convinced. "But not if the stinking redheads send more dragons and we haven't got any on patrol. That wasn't what you'd call efficient." King Swemmel had tried mightily to make efficiency Unkerlant's watchword. His subjects mouthed his slogans--inspectors made sure of that--but they had a good deal of trouble living up to them.

Captain Drogden rubbed his nose. Like Leudast--like most Unkerlanters--he boasted a fine hooked beak, one that was sometimes vulnerable to cold weather. He said, "I hear there's a new commander at the closest dragon farm. The old commander's gone to a penal battalion."

"Oh," Leudast said, and said no more. Once in a while, the men who fought in a penal battalion escaped it by conspicuous, death-defying heroism. Far more often, they simply died softening up tough Algarvian positions so the soldiers who followed them in the attack got a better chance of success.

"Chief dowser almost went with him," Drogden added.

"Rain must have saved the mage," Leudast said. His superior nodded. Dowsers spotted dragons at long range by sorcerously detecting the motion of their wingbeats. Finding that motion in the midst of millions of raindrops taxed dowsing rods, spells, and the men who used them.

A gang of Yaninan peasants squelched by, carrying timbers for the Unker-lanter artificers and their bridge-building. The Yaninans were as swarthy as Unkerlanters, but they were mostly lean men with long faces, not stocky men with broad cheekbones. They grew bushy mustaches, where Leudast and his countrymen shaved when they got the chance. They wore tight tunics, trousers so tight they were almost leggings, and, absurdly, shoes with pompoms on them. They also wore unhappy expressions at being shepherded along by a couple of Unkerlanter soldiers with sticks.

"Our allies," Leudast said scornfully.

Drogden nodded. "As long as we don't turn our backs on them, anyhow. Powers below eat them for kicking us when we were down, and for getting away with switching sides when they did. We could have smashed them right along with the redheads."

"Probably, sir," Leudast agreed. "But the way I look at it is like this: their whole fornicating kingdom is a penal battalion these days. And they know it, too--look at their faces."

The regimental commander thought about that, then laughed and nodded and slapped Leudast on the back. "A penal kingdom," Drogden said. "I like that, curse me if I don't. You're dead right. King Swemmel will find a way to make them pay."

"Of course he will," Leudast said. Both men took care to speak as if they were paying the king a huge compliment. No one in Unkerlant dared speak of Swemmel any other way. You never could tell who might be listening. One of the oldest sayings in Unkerlant was, When three men conspire, one is a fool and the other two are royal inspectors. It held a lot of truth under any king who ruled from Cottbus. Under Swemmel, who'd had to win a civil war against his twin brother before taking the throne, and who scented plots whether they were there or not, it might as well have been a law of nature.

A few eggs burst, perhaps a quarter of a mile away: Algarvian egg-tossers, feeling for the new bridge. The bursts weren't particularly close to it, either. A couple of the Yaninans in the work gang dropped the log they were carrying and made as if to run. One of the soldiers with them blazed a puff of steam from the wet ground in front of them. They probably didn't understand his curses, but that message needed no translation. They picked up the log and went back to work.

"Surprised he didn't blaze' em," Drogden remarked.

"Aye," Leudast said. "Back when the war was new--when we moved into Forthweg, or we'd just started fighting the Yaninans--I'd've taken cover when I heard bursts that close. I know better than to bother now. Those dumb buggers don't."

"You've been in it from the start?" Drogden asked.

"I sure have, sir," Leudast answered. "Before the start, even--I was fighting the Gongs in the Elsung Mountains, way out west, when Algarve's neighbors declared war on her. I was in Forthweg when the redheads jumped on our back, and I've been trying to kill those whoresons ever since. They've been trying to kill me, too, but they only blazed me twice. Add it all up and I've been pretty lucky."

"Matter of fact, they've got me twice, too," Drogden said. "Once in the leg, and once--" He held up his left hand. Till he did it, Leudast hadn't noticed he was missing the last two joints of that little finger.

"Were you in from the very beginning, too?" Leudast asked him.

"I've been in the army since then, aye, but I only went to the front a year and a half ago," Drogden said.

"Really?" Leudast said. "You don't mind my asking, sir, how did you manage to stay away so long?" Who kept you safe? went through his mind. So did, Who finally got angry enough at you to make you come work for a living like everybody else?

But Drogden said, "For a long time, I was in charge of one of the big behemoth-breeding farms in the far southwest. It was crazy there, especially after the redheads started overrunning so many of the farms here in the east. We were getting breeding stock and fodder out as best we could, and sending the animals and everything else across the kingdom so we could go on breeding them in places where the enemy's dragons couldn't reach. We did it, aye, but it wasn't easy."

"I believe that," Leudast said. There had been plenty of times, the first year and a half of the war, when he'd wondered if the kingdom would hold together. There had been more than a few times when he'd feared it wouldn't. He went on, "You had an important job, sir. What are you doing here?"

With a shrug, Drogden replied, "They replaced me with a man who knew behemoths but who'd lost an arm. He couldn't fight any more, but he could be useful in my old slot. That freed me up to go into battle. Efficiency."

"Efficiency," Leudast echoed. For once, he didn't feel like a hypocrite saying it. The move Captain Drogden described made good sense, even if he might have preferred to stay thousands of miles away from the war. On the other hand..."Uh, sir? Why didn't they put you in among the behemoth-riders, if you were in charge of a breeding farm?"

"Actually, I trained as a footsoldier," Drogden answered. "Raising behemoths was the family business. I joined the army because I didn't feel like going into it." He laughed a brief, sardonic laugh. "Things don't always work out the way you plan."

"That's true enough," Leudast agreed. A couple of more Algarvian eggs burst. These were a little closer, but not enough to get excited about. He went on, "If things had worked out the way the redheads planned, they'd have marched into Cottbus before the snow fell that first winter of the war."

"You're right," Drogden said. "From what I've seen, Mezentio's men are almost as smart as they think they are. That makes them pretty cursed dangerous, on account of they really are a pack of smart buggers."

"We've seen that, curse them," Leudast said.

His regimental commander nodded. "Sometimes, though, they think they can do more than they really can. That's when we've made 'em pay. And now, by the powers above, they'll pay plenty."

"Aye." Savage hunger filled Leudast's voice. Like almost all Unkerlanter soldiers who'd seen what the Algarvians had done with--done to--the part of his kingdom they'd occupied, he wanted Algarve to suffer as much or more.

Drogden looked up to the dripping sky. A raindrop hit him in the eye. He rubbed at his face as he said, "I hope the weather stays bad. The worse it is, the more trouble the Algarvians will have hitting that bridge--and however many others we're building across the Skamandros."

"When the bad weather comes, that's always been our time." Leudast started to say something more--to say that, if not for Unkerlant's dreadful winters, the redheads might well have taken Cottbus--but held his tongue. Drogden might have reckoned that criticism of King Swemmel. The fewer chances you took, the fewer risks you ran. Leudast looked across the Skamandros again. Facing the enemy, he had to take chances. Facing his friends, he didn't.

Sunshine greeted him when he woke up the next morning. At first, he took that with a shrug. But then, remembering Captain Drogden's words, he cursed. The business ends of some large number of heavy sticks poked up to the sky on the west bank of the Skamandros. Any Algarvian dragons that did dive on the bridge wouldn't have an easy time of it. Mezentio's dragonfliers hadn't had it easy the last time they attacked, either, but they'd wrecked the bridge.

Leudast ordered his own company forward, all the way up to the edge of the river. The beams from their sticks couldn't blaze a dragon from the sky without the wildest luck, but they might wound or even kill a dragonflier. That was worth trying. "The Algarvians will throw everything they've got at us," he warned his men. "They can't afford to let us get a foothold on the far side of the Skamandros."

As if to underscore his words, a flight of Unkerlanter dragons, all painted the same rock-gray as his uniform tunic and cloak, flew low over the river to pound the Algarvian positions on the eastern side. The soldiers nodded approvingly. If the redheads were catching it, they would have a harder time dishing it out.

And when the Algarvian strike at the bridge came, Leudast didn't even notice it at first. One dragon, flying so high that it seemed only a speck in the sky? He was tempted to laugh at Mezentio's men. A few of the heavy sticks blazed at it. Most didn't bother. They had no real hope of bringing it down, not from that height.

He didn't see the two eggs the dragon dropped, either, not till they fell far enough to make them look larger. "Looks like they'll land on the redheads," one of his men said, pointing. "Serve 'em right, the bastards."

But it did not do to depend on the Algarvians to be fools. As the eggs neared the ground, they suddenly seemed to swerve in midair, and those swerves brought them down square on the bridge over the Skamandros. A long length of it tumbled into the river. "What sort of sorcery is that?" Leudast howled.

He got no answer till that evening, when he put the same question to Captain Drogden. "The redheads have something new there," the regimental commander replied, with what Leudast reckoned commendable calm. "Steering eggs by sorcery is hard even for them, so they don't do it very often, and it doesn't always work."

"It worked here," Leudast said morosely. Drogden nodded. The Unker-lanters stayed on the west bank of the Skamandros a while longer.

...

Hajjaj was glad to return to Bishah. The Zuwayzi foreign minister was glad he'd been allowed to return to his capital. He was glad Bishah remained the capital of the Kingdom of Zuwayza, and that Unkerlant hadn't chosen to swallow his small, hot homeland after knocking it out of the Derlavaian War. But, most of all, he was glad to have escaped from Cottbus.

"I can understand that, your Excellency," Qutuz, his secretary, said on the day when he returned to King Shazli's palace. "Imagine being stuck in a place where they wear clothes all the time."

"It's not so much that they wear them all the time," Hajjaj replied. Like Qutuz, he was a lean, dark brown man, though his hair and beard were white rather than black. And, like Qutuz, like almost all Zuwayzin, he wore only sandals and sometimes a hat unless meeting with foreigners who would be scandalized at nudity. He groped for words: "It's that they need to wear them so much of the time, that they would really and truly die if they didn't wear them. Until you've been down to the south, you have no idea what weather can do--none, I tell you."

Qutuz shuddered. "That probably helps make the Unkerlanters what they are."

"I wouldn't be surprised," Hajjaj answered. "Of course, other Derlavaians, ones who don't live where the weather's quite so beastly, wear clothes, too. I wouldn't care to guess what that says about them. And the Kuusamans have a climate every bit as beastly as Unkerlant's, and they are, by and large, very nice people. So you never can tell."

"I suppose not," his secretary said, and then, in musing tones, "Kuusamans. We haven't seen many of them in Zuwayza for a while."

"No, indeed," Hajjaj agreed. "A few captives from sunken ships, a few more from leviathans killed off our shores, but otherwise..." He shook his head. "We'll have a lot of closed ministries opening up again before long."

"Ansovald is already back at the Unkerlanter ministry," Qutuz observed.

"So he is," Hajjaj said, and let it go at that. He despised the Unkerlanter minister to Zuwayza, who was crude and harsh even by the standards of his kingdom. He'd despised him when Ansovald served here before Unkerlant and Zuwayza went to war, and he'd despised him down in Cottbus, when Ansovald had presented King Swemmel's terms for ending the war to him. Ansovald knew. He didn't care. If anything, he found it funny. That only made Hajjaj despise him more.

"Kuusamans," Qutuz repeated. "Unkerlanters." He sighed, but went on, "Lagoans. Valmierans. Jelgavans. New people to deal with."

"We do what we can. We do what we must," Hajjaj said. "I've heard that Marquis Balastro did safely reach Algarve."

"Good news," Qutuz said, nodding. "I'm glad to hear it, too. Balastro wasn't a bad man, not at all."

"No, he wasn't," Hajjaj agreed, wishing the same could be said of the cause for which Algarve fought.

Having the Algarvian ministry standing empty felt as strange as imagining the others filled. Not even Hajjaj could blame Swemmel of Unkerlant for requiring Zuwayza to renounce her old ally and cleave to her new ones. He'd never liked many of the things Algarve had done; he'd loathed some of them, and told Balastro so to his face. But any kingdom that could help Zuwayza get revenge against Unkerlant had looked like a reasonable ally. And so...and so Zuwayza had gambled. And so Zuwayza had lost.

With a sigh, Hajjaj said, "And now we have to make the best of it." The Unkerlanters had made Zuwayza switch sides. They'd made her yield land, and yield ports for her ships. They'd made her promise to consult with them on issues pertaining to their dealings with other kingdoms--that particularly galled Hajjaj. But they hadn't deposed King Shazli and set up the Reformed Principality of Zuwayza with a puppet prince, as they'd threatened to do during the war. They hadn't deposed Shazli and set up Ansovald as governor in Bishah, either. However much Hajjaj disliked Swemmel and his countrymen, they might have done worse than they had.

And they would have, if they weren't still fighting hard against Algarve--and not quite so hard against Gyongyos, Hajjaj thought. Well, if they've chosen to be sensible, I won't complain.

One of the king's serving women came into the office and curtsied to Hajjaj. "May it please your Excellency, his Majesty would confer with you," she said. But for some beads and bracelets and rings, she wore no more than Hajjaj and Qutuz. Hajjaj noticed her nudity more than he would have if he hadn't just come from a kingdom where women shrouded themselves in baggy, ankle-length tunics.

"Thank you, Maryem," he replied. "I'll come, of course."

He followed her to Shazli's private audience chamber. He enjoyed following her; she was well-made and shapely. But I don't stare like the pale-skinned foreigners who drape themselves, he thought. We may scandalize them, but who really has the more barbarous way of looking at things? He chuckled to himself. If he hadn't studied at the University of Trapani in Algarve, such a notion probably never would have occurred to him.

"Your Majesty," he murmured, bowing as he came into King Shazli's presence.

"Always a pleasure to see you, your Excellency," Shazli replied. He too was nude, but for sandals and a thin gold circlet on his brow. He was a slightly plump man--nearing forty now, which startled Hajjaj whenever he thought about it--with a sharp mind and a good heart, though perhaps without enormous force of character. Hajjaj liked him, and had since he was a baby. "Please, sit down," the king said. "Make yourself comfortable."

"Thank you, your Majesty." Zuwayzin used thick rugs and piles of cushions in place of the chairs and sofas common elsewhere in Derlavai. Hajjaj made himself a mound of them and leaned back against it.

Shazli waited till he'd finished, then asked, "Shall I have tea and wine and cakes sent in?"

"As you wish, your Majesty. If you would rather get down to business, I shan't be offended." Zuwayzin wasted endless convivial hours in the ritual of hospitality surrounding tea and wine and cakes. Hajjaj often used them as a diplomatic weapon when he didn't feel like talking about something right away.

"No, no." Shazli hadn't had a foreign education, and clung to traditional Zuwayzi ways more strongly than his much older foreign minister. And so another serving girl fetched in tea fragrant with mint, date wine (Hajjaj actually preferred grape wine, but the thicker, sweeter stuff did cast his memory back to childhood), and cakes dusted with sugar and full of pistachios and cashews. Only small talk passed over tea and wine and cakes. Today, Hajjaj endured the rituals instead of enjoying them.

At last, the king sighed and blotted his lips with a linen napkin and remarked, "The first Unkerlanter ships put in at Najran today."

"I hope they were suitably dismayed," Hajjaj remarked.

"Indeed," King Shazli said. "I am given to understand that their captains made some pointed remarks to the officers in charge of the port."

"I warned Ansovald when I signed the peace agreement that the Unker-lanters would get less use from our eastern ports than they seemed to expect," Hajjaj said. "They didn't seem to believe me. The only reason Najran is a port at all is that a ley line runs through it and out into the Bay of Ajlun." He'd been there. Even by Zuwayzi standards, it was a sun-blazed, desolate place.

"You understand that, your Excellency, and I also understand it," Shazli said. "But if the Unkerlanters fail to understand it, they could make our lives very unpleasant. If they land soldiers at Najran..."

"Those soldiers can make the acquaintance of the Kaunians who managed to escape from Forthweg," Hajjaj said. "I don't know how much else they could do. Even now, when the weather is as cool and wet as it ever gets, I can hardly see them marching overland to Bishah. Can you, your Majesty?"

"Well, possibly not," the king admitted. "But if they want an excuse to revise the agreement they forced on us..."

"If they want such an excuse, your Majesty, they can always find one." Hajjaj didn't often interrupt his sovereign, but here he'd done it twice in a row. "My belief is that this is nothing but Unkerlanter bluster."

"And if you are wrong?" Shazli asked.

"Then Swemmel's men will do whatever they do, and we shall have to live with it," Hajjaj replied. "That, unfortunately, is what comes of losing a war." The king grimaced but did not answer. Hajjaj heaved himself to his feet and departed a little later. He knew he hadn't pleased Shazli, but reckoned telling his sovereign the truth more important. He hoped Shazli felt the same. And if not...He shrugged. He'd been foreign minister longer than Shazli had been king. If his sovereign decided his services were no longer required, he would go into retirement without the slightest murmur of protest.

Shazli gave no sign of displeasure. Hajjaj almost wished the king had, for the next day Ansovald summoned him to the Unkerlanter ministry. "And I shall have to go, too," he told Qutuz with a martyred sigh. "The price we pay for defeat, as I remarked to his Majesty. Given a choice, I would sooner visit the dentist. He enjoys the pain he inflicts less than Ansovald does."

Hajjaj dutifully donned an Unkerlanter-style tunic to visit Ansovald. He minded that less than he would have in high summer. Calling on the Jelgavans and Valmierans means wearing trousers, he thought, and imagined he was breaking out in hives at the mere idea. Another sigh, most heartfelt, burst from him.

Two stolid Unkerlanter sentries stood guard outside the ministry. They weren't so stolid, however, as to keep their eyes from shifting to follow good-looking women going by with nothing on but hats and sandals and jewelry. With luck, the sentries didn't speak Zuwayzi--some of the women's comments about them would have flayed the hide from a behemoth.

Ansovald was large and bluff and blocky. "Hello, your Excellency," he said in Algarvian, the only language he and Hajjaj had in common. Hajjaj savored the irony of that. He had little else to savor, for Ansovald bulled ahead: "I've got some complaints for you."

"I listen." Hajjaj did his best to look politely attentive. Sure enough, the Unkerlanter minister fussed and fumed about the many shortcomings of Najran. When he finished, Hajjaj inclined his head and replied, "I am most sorry, your Excellency, but I did warn you about the state of our ports. We shall do what we can to cooperate with your captains, but we can only do what we can do, if you take my meaning."

"Who would have thought you ever told so much of the truth?" Ansovald growled.

Staying polite wasn't easy. I do it for my kingdom, Hajjaj thought. "Is there anything more?" he asked, getting ready to leave.

But Ansovald said, "Aye, there is."

"I listen," Hajjaj said again, wondering what would come next.

"Minister Iskakis tells me you've got his wife--Tassi, I think the bitch's name is--at your house up in the hills."

"Tassi is not a bitch," Hajjaj said, more or less truthfully. "Nor is she Iskakis' wife: she has received a divorce here in Zuwayza."

"He wants her back," Ansovald said. "Yanina is Unkerlant's ally nowadays, and so is Zuwayza. If I tell you to give her back, you bloody well will."

"No," Hajjaj said, and enjoyed the look of astonishment the word brought to the Unkerlanter's face. He also enjoyed amplifying it: "If Iskakis had her back, he would use her as he uses boys, if he used her at all. He prefers boys. She prefers not being used so. Unkerlant is indeed Zuwayza's ally, even her superior. I admit it. But, your Excellency, that does not make you into my master, not on any individual level. And so, good day. Tassi stays." He enjoyed turning his back and walking out on Ansovald most of all.

Copyright © 2004 by Harry Turtledove

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details