Added By: Administrator

Last Updated:

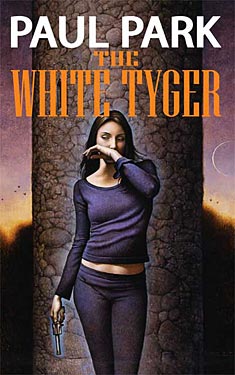

The White Tyger

| Author: | Paul Park |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2007 |

| Series: | A Princess of Roumania: Book 3 |

|

1. A Princess of Roumania |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Many girls daydream that they are really a princess adopted by commoners. In the case of teenager Miranda Popescu, this is literally true. Because she is at the fulcrum of a deadly political battle between conjurers in an alternate world where "Roumania" is a leading European power, Miranda was hidden by her aunt in our world, where she was adopted and raised in a quiet Massachusetts college town.

The narrative is split between our world and the people in Roumania working to protect or to capture Miranda: her Aunt Aegypta Schenck versus the mad Baroness Ceaucescu in Bucharest, and the sinister alchemist, the Elector of Ratisbon, who holds her true mother prisoner in Germany. This is the story of how Miranda -- with her two best friends, Peter and Andromeda -- is brought back to her home reality. Each of them is changed in the process and all will have much to learn about their true identities and the strange world they find themselves in.

Excerpt

Chapter One

A Radioactive Incident

She lay dozing in a bed of pine needles in the Mogosoaia woods, wrapped in a gray shawl against the chilly summer night. In her hand was a letter from her aunt Aegypta, gone now five years. Ma petite chère . . .

Waiting for darkness, surrounded by enemies, she lay on the west bank of the Colentina River in a stand of old trees, nineteen kilometers northwest of Snagov Portal, the tram line, and the broken wall of Bucharest.

But in her dreams she was far away. Miranda had discovered—or was it a coincidence?—that if she closed her eyes like this, with the onionskin pages of her aunt's final letter clasped between her fingers, images would come to her in the moment before sleep, images that were new to her, though on waking, she could recognize them as memories.

At that instant she imagined her seventh birthday party, which she had celebrated in Mamaia by the seaside. English fashion, her aunt had arranged a picnic on the sand dunes with the servants' children, and there had been small cakes and ices. The Chevalier de Graz had stood above them, guarding against an accident or an assault, though he was dressed in his best uniform and ornamental braid.

Now he also stood watching her, twelve or even seventeen years later, scruffy and disheveled but still vigilant. In his left hand he held her father's pistol. His right hand ached from his wound. He was looking toward the river and the ford, where under moonlight they would learn if they'd escaped their pursuers' net. There was nothing for him to do but wait and watch till then, and take a confused comfort in Miranda's presence. Bending down in the uncertain light, de Graz could just make out the small French words under her thumb: . . . si vous êtes comme je crois . . . If you are as I think a princess of Roumania . . .

A lock of her dark hair had fallen over her face. She mumbled something. The letter slipped from her fingers and fell open. But de Graz was more interested in studying her cheek and lips, feeling the tug of small emotions he didn't understand.

He would have scorned to read further even if he'd been curious, even if he'd been able to decipher in the half-light Aegypta Schenck von Schenck's tiny handwriting. Casting his mind forward into the next hour, biting his lips with a nervousness that nevertheless contained an admixture of wordless joy, he would not have had the patience for an abstract argument of any kind: My dear niece, by this time you must suspect that there is more to the world than the evidence of your senses. By this time you might picture to yourself our globe with its little circle of illumination, a circle with its center in Great Roumania, and showing at the limit of its bright circumference the nations of Africa and Asia, and to the west the North American wilderness, dark and trackless beyond the Henry Hudson River. Closer to home we find the Byzantine Turks, and Russia, and the German Republic with its tributary states. We find barbaric Italy and unpopulated France, and Iberia behind the curtain of ice mountains. In the North Sea there are the submerged remnants of the British Islands, a proud nation once.

You know all this. It is what everyone knows, every shopkeeper and office clerk. I want to bring you news of another country just as real as these, but it is nevertheless hidden or secret, a landscape of the heart, you might call it, or of dreams, but whose influence can be seen in every natural phenomenon. This is a country that the dead can visit and not only the dead. My dear, though in the ordinary world you must sometimes feel feeble and alone, please take consolation in imagining yourself a personage of terrible importance in this secret country, if you are as I think a princess of Roumania. I mean if you can find the strength to do what's right, or even if you can't.

You must suspect all this already. Everyone suspects it. Not to suspect it would make life intolerable. But faith is one thing, action is another, and science is a third. Now I must explain to you that access to this hidden world can be achieved in several ways which vulgar people might call conjuring, a word I despise because of its implication of fakery and fraud. Because of it, many intelligent persons cannot even reach out their hands to touch the strands we others grope for blindly, the nets that make a pattern for the universe, and that constrain the many-colored incidents of our experience like a school of brainless fish. . . .

In Mogosoaia the sun was setting. But earlier that day, two men had stood on a work site near the town of Chiselet on the Bulgarian frontier. "Intelligent persons," in the words of Aegypta Schenck, they would have rejected with contempt the entire contents of her letter, dismissing it as criminal superstition. But their agreement on these matters had not helped them to explain the facts at hand. Surveying the wreck of the Hephaestion, the night train from Constantinople to Bucharest, they were full of doubt, dissatisfied with their own opinions and each other's.

The passenger compartments had tumbled off the high embankment. Three cars lay on their sides. Roumanian work crews, pressed into service from the town, labored with dour resentment under their German overseers. They had not yet managed to repair the tracks. For the time being, all trains had been rerouted to the old line through Calarasi.

The Hephaestion had driven over a mine that had blown up the baggage car. Pushed in front of the engine as a precaution, it had exploded and burned. Nothing much was left of it now. This was due not so much to the power of the mine as to the effect of the ordnance that had been packed inside the car, contravening international and local regulations.

"Many things . . . are not good," said Joachim Beck.

Dispatched as a consultant by the German embassy, he combined several useful areas of expertise. A medical doctor and a professor of industrial design, he nevertheless spoke Roumanian like a three-year-old. This was especially galling to Radu Luckacz, who was fluent in all central European languages. To labor in this unproductive way, to ignore all Luckacz's attempts to answer him in his own language, was obviously a form of condescen-sion. The other possibility—that the doctor was playing some kind of doughy, Teutonic practical joke—Luckacz had examined briefly and then discarded. There was nothing in the German's cold fat features to suggest a sense of humor.

And of course the circumstances were quite serious. There appeared to be some sort of epidemic in the town. Whether it had been caused by exposure to a biological, chemical, or radioactive contaminant, or was unconnected to the accident—none of that was sure. The work crews, however, had been recruited under duress. The men wore gauze masks over their faces, and so far none of them had gotten sick. Since the previous day, German cavalry were stationed in the town.

Now the German doctor and the Roumanian police chief walked along the berm under the embankment, a quarter kilometer from the wreck. Several lead canisters had been laid out in a line beside a bush. They were evidence of the forbidden cargo and had broken open during the explosion; they were empty now. They had contained African pitchblende or radium. Luckacz was unsure of the details, which had not been shared with him.

Copyright © 2007 by Paul Park

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details