Added By: valashain

Last Updated: illegible_scribble

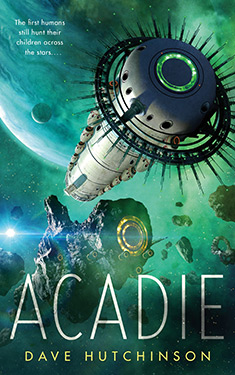

Acadie

| Author: | Dave Hutchinson |

| Publisher: |

Tor.com Publishing, 2017 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novella |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Artificial Intelligence Colonization Space Opera |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

The Colony left Earth to find their utopia--a home on a new planet where their leader could fully explore the colonists' genetic potential, unfettered by their homeworld's restrictions. They settled a new paradise, and have been evolving and adapting for centuries.

Earth has other plans.

The original humans have been tracking their descendants across the stars, bent on their annihilation. They won't stop until the new humans have been destroyed, their experimentation wiped out of the human gene pool.

Can't anyone let go of a grudge anymore?

Excerpt

1

It was the morning after the morning after my hundred and fiftieth birthday, and a terrible noise was trying to wake me up.

I stayed asleep while my subconscious did all the work and sorted through the menu of possible noises that might have been annoying enough to disturb me. Doorbell? Disconnected it. Kitchen? Been incapable of cooking anything since the day before yesterday. Decompression alarm? Not humanly possible to do anything when you hear a decompression alarm but grab an emergency suit or head for a panic room. Phone? Turned it off and only one person had the codes to turn it back on.

Ah, bollocks.

"What?" I muttered.

"Well, good morning, Mr. President," a voice purred just in front of my face. "And how are we today?"

"Not funny," I said. "Not funny at all."

"We've got a situation," she said.

"You've got a situation," I told her. "I'm still on leave."

"Sorry, this needs command authority."

"You've got command authority, for Christ's sake."

"Not for this. There's been an incursion."

I groaned. "It's a rock. It's always a rock."

"No such luck," she said. "Get over to the office, Duke. This is the real thing." And she added brightly, "And it happened on your watch. How great is that?"

I opened my eyes and my spirit recoiled. "Where?" The voice reeled off a thirty-digit string of numbers which, even after a hundred years, was still mostly meaningless to me. "That's pretty deep downsystem, isn't it?"

"Man gets a cigar," she said.

"How did the dewline miss it?"

"This is just one of the many questions we're asking ourselves at the moment. You see? An actual situation. Come on, Duke, get your game face on. Up and at 'em." And she hung up.

I stayed in my cocoon for a few more moments, looking around the bedroom. It was a nice bedroom, roomy and dark blue and almost completely spherical, its walls covered in recessed handles for cupboards and drawers. Some of my clothes were drifting gently across my field of view. It was a really nice bedroom, but I wasn't going to get to stay in it much longer today. I crossed my eyes and concentrated, and a complex of cells, grown on the surface of my liver without my knowledge or permission during some tweak or other, began to do a magic trick on my hangover. It was a big hangover, and the magic trick was going to take a little while. It was going to need fuelling or I was going to wind up hypoglycaemic, so I split open the seams of the cocoon and drifted across the bedroom until I hit the opposite wall, where I tugged at the door handle.

The moment the door opened the cats barrelled in, squeaking and spitting and twisting in the air, the black one chasing the white one. The black one hard-landed on the far wall on all four feet, bounced off, and caught the white one in mid-air, and they became a furious ball of black and white fur from which screeching noises erupted.

"Stop fighting," I told them as I made my way out into the main room of the apartment. They ignored me. "Okay," I muttered. "Fine. Carry on fighting." I'd inherited the cats, along with the apartment, from an upsystem miner who had suffered a fatal but ill-defined accident. He had been, by all accounts, a colossal son of a bitch who had abused his pets. I was entirely opposed to animal cruelty, but I drew the line at sharing my bedroom with a pair of freefall cats.

I drifted into the kitchen and switched on the coffee maker, then I went into the bathroom, strapped on the breathing mask, and hung in the centre of the room while jets of very hot water beat me up. When the cycle finished, I switched it on again. Then once more for luck. Then I let the pumps drain the room and the hot-air blowers dry me off and went back into the kitchen to root around for something to eat. There wasn't much, but the coffee maker provided a large bulb of a hot caffeine-containing fluid, which was important because the complex of magic cells on the surface of my liver metabolised caffeine in order to do their thing. If they didn't have caffeine, they metabolised blood sugar, but that wasn't recommended. It was not coffee as I remembered it, though, because the Writers had still not managed to get coffee to grow in zero-gee. You'd think that would be a simple thing for smart people, particularly smart people whose previous lives had pretty much been fuelled by coffee and complex carbohydrates, but no. I drank the large bulb and refilled it and dug out some clothes that didn't smell too much, then I put a wingsuit on over them, opened the front door, and stood on the porch.

The view from my porch was pretty special, even in an age of wonders. I looked out through a scene that was like a wraparound rain forest, the mutant kudzu that half-filled the hab and gave it its structural strength as well as taking care of certain aspects of life support. It was green and misty and cool and hundreds of little specks were unhurriedly winging through it, swooping gracefully around bracing roots almost a metre thick.

A couple of the specks flapped by, Kids with great angel wings. They waved as they passed and made a couple of incomprehensible jokes and I waved back and told them to go fuck themselves, and in this way the hab became aware that its President was up and about and pretty much as grumpy as usual and all was right with the world.

Which it wasn't.

I made sure the door behind me was locked, then I flung open my arms and jumped out into the yawning green cavern of my home.

* * * * *

City Hall was near the centre of the hab, nestled in the heart of a huge clump of kudzu. I managed an untidy landing on the verandah, stripped off my wingsuit, and went inside.

Like pretty much every other building in the Colony, City Hall was a sphere of construction polyp, but it was the biggest and oldest structure here, a gnarled pearlescent ball the size of an ocean liner. It was big enough, in the event of a very, very large disaster, to act as a panic room for the whole population of the hab, but most of the time it was all but empty, occupied by skeleton staffs of administrators and engineers and techs.

It also housed my office, which was nothing much to boast about. I hadn't spent more than fifty minutes there since my term began eight months ago, and I couldn't in all honesty have directed anyone through City Hall's winding tunnels to find it.

Fortunately, I wasn't going to my office. I was going to The Office, which was easier to find because it was much bigger and located right at the heart of the structure. It was also, when I finally emerged from the tunnel, full of worried-looking people having hushed conversations over monitors and tapboards and in front of infosheets.

"Happy birthday," Connie said as I drifted over.

"Hm," I said. "So, what have we got?"

"We've got a bogey," she said, and she pointed to a big infosheet on the other side of the room. The infosheet showed a depthless field of black, and right in the middle of it floated a probe. It was about fifteen metres long and five wide, an off-white cylinder with the letters BoC stencilled on the side. At one end was a big fat conical meteorite shield of spun ice, and at the other was the skinny bell-shape of a high-yield fission engine exhaust. In between was a lumpy, cluttered landscape of hyperdrive motor radomes and sensor pods and squeeze-fusion microquads. It was a fairly simple design, cheap to manufacture; the Bureau of Colonisation built hundreds of them every year and sent them off on fast-flyby missions to unmapped solar systems. My heart sank.

"Not a rock, then," Connie said.

"Not a rock," I agreed. I swore. "Where's this picture coming from?"

She told me, and I swore some more. A lot more.

* * * * *

The Colony didn't have a government, as such. Each hab elected an annual representative to a sort of loose advisory body that kind of kept things bumping along. On the principle that anyone seeking political power wasn't to be trusted with it, the only people who were allowed on the advisory body were those who absolutely did not want to be on it. This included pretty much everyone, so the two or three months leading up to elections saw a flurry of pantomime campaigning enthusiastic enough to disqualify each candidate from office. I'd done some good campaigning myself in the past and managed to dodge the bullet, but last time the elections came round I'd been outsystem, giving someone a lift to Nova California. This had been taken as a sign that I couldn't be bothered with politics, and when I got back I found that not only had I been elected but the sneaky bastards had decided my absence proved I truly didn't give a shit and had made me President.

The office of President actually had very little real power. What it did have was a lot of responsibility, of the kind when something is such a hot potato that everyone looks around for someone else to offload it onto. That was me, for the next three and a half years or so. President of the Colony, doer of things nobody else wanted or could be bothered to do, taker of decisions so shitty nobody else wanted to be responsible for them.

* * * * *

If you live all your life on a planet, one of the fundamental things you never really appreciate about space is that, mostly, it all looks the same.

Obviously, there are some caveats to this. Close in to stars or orbiting planets or skirting the edge of a nebula, the scenery can be pretty spectacular. But everywhere else is just stars and emptiness.

That's pretty much all you'll see, even inside a solar system. The movies will kid you that starships zip in and out of hyperspace and pop into systems and see all the planets and asteroids and stuff, but even a solar system with dozens of planets is mostly empty space; if you're unfortunate or even just mildly inattentive it's perfectly possible to fly entirely through one and not see anything but the tiny bright point of the system's sun. At a distance of forty-five AUs, which was where we were, it's not all that hard to miss noticing the sun at all, if it's crappy enough.

At this distance, there was almost as much illumination from the stars as there was from the sun, so we had to use searchlights and image amps to see the probe. The light reflected from the thing's hull washed out the stars. It had come a long way; the conical ice shield looked pitted and eroded.

"And you shot it down," I said.

"Well, not down, as such," said Karl.

I ignored him and raised an eyebrow at Ernie, who just sighed and puffed out her cheeks.

"That thing's radioactive as a bastard," Karl noted. "Are we safe this close to it?"

"Cheap fucking fission drive," Ernie muttered. "Dropping it into my system." She was heavily modded--four arms, hands where her feet should have been, face rewritten into a gargoyle's leer that had no practical purpose, as far as I could see, aside from being off-putting.

"And you shot it down," I said again in an attempt to regain control of the situation.

"Aw, come on, Duke," she complained, gesturing with all four hands at once. "What was I supposed to do?"

"You know what you were supposed to do," I told her. "You were supposed to run silent and watch the damn thing go away."

"Dewline didn't pick it up," she said.

"And much brighter people than you or me are thinking about that right now," I said. "Your job was to call in the sighting and let the thing go, not fire on it."

The three of us were crammed into the control bubble of Ernie's ship, which wasn't a whole lot bigger than the probe. She spent months on her own out here in the system's halo, towing a couple of small hab modules fitted out with centrifuge equipment and smelters and chondrite refineries, mining dead comets for rare-earth metals. When she spotted the probe, she'd dropped the habs and set off in pursuit, and when she was within range she'd cooked it with a mining maser, fired a tether at it, spent almost a fortnight braking it down below solar escape velocity, and towed it back upsystem. Then she'd called us. Not a single one of these actions was in the standard operating procedure.

"You think it got a message out?" Karl said.

I looked at the screen in front of me, the probe floating innocently at the end of its tether.

"Let's hope not," I said. "Otherwise we're all going to be looking for somewhere else to live."

* * * * *

"No offence," said Shaker, "but for a bunch of supposedly bright people, you guys do some stupid things sometimes."

"Leaving aside the fact that I don't belong to the subset 'you guys,' I agree," I said morosely.

"What are you going to do?"

"I'm going to have another drink," I said, waving to attract the bartender's attention. "How about you?"

"Hell, yes."

We were in The Penultimate Bar in Radetzky's Hab, and through the skin of the bubble, I could see the mellow salmon-banded curve of Big Bird. Little Bird, its gigantic moon, was rising above the edge of the planet, all cratered and battered and rocky. It was quite a sight, but I wasn't in the mood.

"But that's not what I meant," Shaker continued.

"No," I said. "I know."

I'd left Ernie to keep an eye on the probe, and Karl to keep an eye on Ernie, and I'd come back downsystem to try to formulate a plan of action, but all possible scenarios kept dropping away. The more I thought about it, the more it became obvious that there really was only one option left.

"Any word on the dewline?" I asked.

"We're running diagnostics as fast as we can. But you're talking about more than a billion satellites, at last count. It's going to take a while."

"No downtime? Blackouts? Cometary perturbations?" I'd learned that last phrase a few years ago. I still had no clear idea what it meant, but it seemed to make the dewline techs think I knew what I was talking about.

"We're working back eighteen months in the records." Shaker sat back and rubbed his eyes. "So far, nothing."

"Go back further."

"Duke, mate," he said seriously, "if that thing's been insystem for a year and a half, we're toast anyway."

"We need to know how it got through," I told him. "We need to know if there were more of them. Ernie really fucked up when she fired on it; if it had some kind of newfangled stealth coating or something, it'll have boiled away."

"Oh dear," he said.

I collected two bulbs of whiskey sour from the bartender. "'Oh dear' about covers it, yes."

"No," he said. "The boss is here."

I looked over at the doorway. "I'm your boss," I told him.

"Not while she's here, you're not."

"You're fired."

We both watched Connie somersault languidly through the doorway, looking around the bar. She saw us, kicked off a support column, and landed neatly in the seat next to us. It was beautiful to watch; I'd have injured half a dozen people and crashed into most of the decor if I'd tried that.

"I was just in your office," she said, snapping her fingers at the bartender. "Lovely office. Really great furniture and fittings. Lacking something, though. I wonder what it could be? Hm..." She made a show of thinking. "Oh yes," she said finally. "That's what it's lacking. You."

"I've been rousted from bed and I've been dragged upsystem and back again and I'm not in the mood, Connie," I told her.

She looked at Shaker. "Now I know you have work to do."

Shaker nodded. "Yup." He undid his seat restraints, pushed off gently, and rose unsteadily into the air. Shaker hadn't been in the Colony very long, and one of the reasons I liked him was that he was no more adept at freefall than I was. He bumped into a couple of people and drifted off towards the exit.

"We were having a meeting," I said when he had gone.

"You were having a drink," she said, taking her own bulb from the bartender. "And I don't like you hanging around with him."

"Shaker's okay."

"He's mundane."

"So am I."

She snorted. "No you're not."

"Yes I am," I said. "And I don't like being told who I can drink with, actually."

Normally, the tone of my voice just bounced right off Connie, but this time she looked at me and shrugged. "You shouldn't drink with subordinates," she mused.

"You're doing it."

She gave up, which was unusual for Connie. "Okay. Fine. Drink with whoever you want. Any ideas?"

"Whomever."

"Don't push your luck, Duke. What do we do?"

"I'm still thinking."

She looked at me.

"We might not need to do anything," I said. "That probe's a heap of junk; it's been popping in and out of target systems for decades. The Bureau expects to lose contact with these things eventually anyway; it barely registers when they do."

"They've already been here," she pointed out.

"Yes," I agreed. "Yes, there is that."

"So why come back?"

"Lots of possible reasons. It could be some university co-funding a one-shot mission to take a look at systems in the Bureau database. Pure research. It could be a small mining outfit paying to be part of the probe's mission profile, looking for commercially useful data."

She passed a hand over her shaven scalp. "It's not any of those things, though."

"No. It's a dangle."

She raised an eyebrow.

I sighed. "You're looking for someone," I said. "You can't be sure where they are, but you can be sure who they are, and if you think hard enough about it you can come up with an idea of the kind of place they might be. You can't physically visit all these places and check them out yourself, so what you do is send out provocations. That's your dangle. And if one of your provocations gets a response, you know you've found something worth checking out."

She blinked at me.

"The Bureau second-guessed the Writers. It's been grand-touring probes through all the systems in its database where it thinks they might be hiding, hoping that one will get shot down."

"Could still be a malf, though."

"So you send a manned follow-up to check it out. If the probe's just broken down or hit something, no harm. On the other hand..."

"How long?"

"The dewline would tell us."

"The dewline didn't spot the probe, and I was talking to Shaker about that when you muscled in."

She ignored that. "Dammit," she said. "We did this once before, you know, before you arrived. We lost two habs; we never did find them."

"I know," I said, although I thought lost was a relative term. For all anyone knew, the populations of those habs had taken a snap vote and elected to use the opportunity to strike off and set up their own colony.

"It was early on; the tech hadn't settled yet, we were still jumpy and unsure of ourselves. We did a proper check of the data afterwards," she went on, looking up at the ceiling of the bar. "There'd been a glitch, made the dewline think we were under attack. We lost forty thousand people, all because of a few crappy lines of code." She looked at me. "We can't do that again, Duke."

"No," I said. "And it's my responsibility, anyway."

* * * * *

I was having dinner in a restaurant on Angel's Rest when a very tall woman came over and sat down opposite me.

It was ice-storm season and Probity City was battened down for the duration. I'd walked out on my job and was gradually burning my way through my savings in a slow drift through the Colonies. I'd spent a year or so with the mining operation in Gliese 581c's asteroid belt, a few months on Holden's Landing, and I'd had the misfortune to arrive on Angel's Rest just as the weather went into its regular decade-long overdrive. Now I was stuck here, watching the figures of my bank balance unspooling and considering going into suspension until the weather calmed down and the ground-to-orbit shuttles were able to take off again. What I shouldn't have been doing was sitting in the expensive restaurant of my expensive hotel and eating an expensive meal. The food was outstanding, though.

I'd just started on my main course when the very tall woman came in. Every head in the place turned in her direction. She was very nearly three metres tall, slim as a willow, stunningly beautiful, and bald as a coot, and she was wearing a clean but much-patched and repaired set of olive-green coveralls. She looked around the restaurant for a few moments as if looking for someone, then she came over to my table, pulled out the chair opposite me, and sat down and folded her hands in her lap. She looked mildly amused about something.

We looked at each other for a few moments, then one of the waiters came over and offered her the menu, but she waved it away. "I'll just have an espresso, thanks all the same," she told him.

"I'm afraid madam will have to order food if she wants to remain in the restaurant," the waiter said.

She stared at him. Even sitting down she was almost as tall as he was. Then she reached out and grabbed a couple of breadsticks from the glass in the middle of the table. She crunched one and grinned at the waiter. "Espresso, thanks," she said, and after another moment he backed away.

I went back to my Kobe beef.

After a minute or so, she said, "I watched your press release. Very funny."

"I'm eating," I said.

She noisily ate another breadstick until it annoyed me enough to make me look up from my meal.

"What makes a man like you quit a job like that?" she pondered, tipping her head to one side.

"If you've seen the release, you'll have a good idea."

She shrugged. "It was a good job, too. Lots of mucky-mucks in the BoC, but not that many high mucky-mucks."

"I'm not talking to the Press," I told her evenly. "I thought I made that clear."

"Oh, I'm not the Press," she said brightly. "I'm not even a groupie--and you do have your fair share, Mr. Faraday. I'm here to offer you a job."

"I don't want a job."

She grinned. "Oh, c'mon, Duke--can I call you Duke?--everybody wants a job."

"I don't."

"Well you can't keep eating that stuff forever, then," she said, nodding at my plate. "Man with expensive tastes and no job, that's trouble."

"I'll manage."

She leaned forward and clasped her hands together on the tabletop. "What if I were to offer you a way to do more than just manage? What if I were to offer you the chance to be part of a great adventure?"

"I'm really trying to have a quiet life, Ms...."

"Lang. Conjugación Lang." She smiled at me and lowered her voice until only I could hear her. "What if I were to offer you a way off this howling nightmare of a planet? Right now?"

"You have some kind of magic spaceship that takes off through seven-hundred-kilometre-an-hour blizzards?"

She wrinkled her nose and grinned coquettishly. "Oh, I have something better than that."

* * * * *

Probity City's spaceport was ringed with underground hangars, and in one of them nestled a little insystem tug, rough and blocky and unsubtle, covered in propulsion nozzles and tetherpoints and battered industrial tech.

"Very funny," I said. I had finished my meal and then, at Conjugación Lang's suggestion, packed what passed for my luggage and followed her down here, two hundred metres below the wind-scoured tundra of the spaceport.

Standing beside me, she nodded. "Good, isn't it?"

The words Something Better Than That were sprayed on the side of the tug in Comic Sans, which really was the least of the little vehicle's problems. It looked as if it could barely get off the ground on a calm midsummer's afternoon, let alone reach orbit in the middle of an ice storm.

I turned to go, but she put a hand on my arm. It was a strong hand. She squeezed gently and I felt a thrill of panic. The Bureau was, in general, too smart and frankly too busy for petty score-settling, but I'd included a couple of ad hominem comments in my press release and the people I'd made them about were vindictive little bureaucrats who couldn't sleep at night unless they had come out on top during the day. I'd probably been responsible for some sleepless nights.

I said out loud for the benefit of the cameras in the hangar, "I claim political asylum."

Lang looked down at me and beamed. "Bless you, Duke, I don't work for the Bureau, this isn't a kidnapping, and I spoofed all the cameras when I first got here. Nobody knows we're here but us." Her expression became serious. "Look. Just hear me out. If you still don't want to come, I'll bring you back and nobody will be any the wiser."

"You're crazy and I want to leave," I told her. But she didn't let go of my arm. Cameras or not, I was faced with the choice of having a fight with a very tall bald woman, or doing what she wanted. I said, "I'm a lawyer. What on earth do you want with a lawyer?"

She bugged her eyes out at me and licked her lips. "Never eaten a lawyer before."

"Look at my face," I said. "Look at my face while I scream in terror."

She let go of me. "What you did, that took stones," she said. "Not the quitting--anyone could have done that. Quitting and publicly criticising the Bureau like that, that's unusual."

Some years previously, a group of colonists had died while in suspension on their way to one of the newer settled worlds. Their families had brought a suit against the Bureau, and I had been one of many, many Bureau lawyers defending it. I hadn't actually come to any great liking for any of the individuals involved, but there had been instances of sharp practice involved in assembling our defence with which I was not in the slightest bit comfortable.

I'd taken my concerns to my superiors, who immediately slapped me down and suggested that I take a week or so off to think over my position, without pay.

Now, I was a grown-up and I knew the road. I was at least self-aware enough to know that the world was not perfect and that monolithic entities such as the Bureau of Colonisation always get their way, and I was realistic enough to realise that either you get on board or you get bulldozed. It was, therefore, still something of a mystery to me why, after a couple of days mooching around my apartment, I had found myself drafting a letter of resignation and a press release which made me, for an hour or two, one of the most recognisable faces on Earth.

My departure and whistleblowing had not affected the case at all, but it had made me feel better. Not particularly heroic or righteous, but better about myself, which counts for a lot sometimes. It had not made me feel in any way special or valuable.

I said, "Other lawyers are available."

She laughed. "We don't want a lawyer, Duke, although a lawyer might come in handy from time to time. No, we want you. Now. Want to take a ride?"

I sighed. "Lead the way."

We cycled through the tug's little airlock--there was just barely room for us both--and into the cramped control room. Lang sat down in one of the control couches and started punching buttons and waking up displays.

"Sit down, Duke," she told me.

I stood where I was, my tote slung over my shoulder, genuinely curious about a number of things. Firstly, whether the tug could actually take off at all. Secondly, how it was going, as she claimed, to get into orbit when it was a basically non-aerodynamic shape which would be flying through a storm of hail powerful enough to turn a skyscraper into an eroded stump. Thirdly, how she was planning to take off when spaceport control would have to open the doors at the end of the hangar which connected it with the tunnel leading to the surface. This was, I decided, going to be one of the shorter trips I had taken.

"Well, you might want to hang on to something, then," she said.

I didn't move.

She shrugged irritably. "Okay," she said. "I gave you fair warning." And she typed a couple of commands and I was falling.

I flailed my arms and legs and windmilled in mid-air, my inner ear refusing to process anything that made any sense. I threw up my expensive dinner, and it became a big sphere of vomit that drifted swiftly across the cabin, hit a bulkhead, and exploded into hundreds of smaller spheres of vomit. I threw up again.

"Oops," said Lang. "Well, you can't say I didn't tell you so." She reached up and snagged my belt and pulled me down until I could grab onto one of the armrests of the vacant control couch and strap myself in. She, meanwhile, was jackknifing expertly out of her own couch and unclipping a hose from a cupboard to vacuum up my dinner.

I sat panting in the control couch, my balance going haywire. And then I saw the centre display on the control panel and for a moment I forgot about everything.

We were in orbit.

Angel's Rest hung in the display, a great dirty white ball of cloud. One side of it was dimpled by dozens of depressions where ice tornadoes tracked back and forth across the uninhabited Western Continent, a place so truly awful that no one had bothered to give it a name. There were plans to build great underground arcologies there one day, but that was something for the far future because for eleven months of the year it was literally impossible to travel anywhere in the west.

That there were people here at all was due mainly to a number of coincidences. The Bureau's policy regarding exploration was to make it as cost-effective as possible; it used telescopes in Earth's cometary halo to identify stars with exoplanets, then sent unmanned probes to them for a closer look. There were a lot of alien solar systems out there, so the probes usually had an itinerary running into the hundreds, and each initial probe was tasked for a simple fast-flyby, a snapshot of rocky worlds and gas giants and asteroid belts, with a special focus on any planets within the liquid-water band of that particular sun.

Stars with likely looking worlds--roughly Earth-sized rocky bodies within the liquid-water belt--got a second visit. The second wave of probes were tasked to stick around longer and do a proper survey of the system, but they were programmed with if/then loops--if the planet has an atmosphere then conduct a spectroscopic analysis; if the planet has no atmosphere then move on to the next target, that kind of thing--and that sort of programming is open to all kinds of errors.

In the case of Angel's Rest, the second probe arrived near the beginning of the planet's temperate phase. It found a rather chilly but still habitable world at the outside edge of the liquid-water zone--but Earth is in a similar position, and nobody's ever complained about that--with a breathable atmosphere. It finished its tests, transmitted them back to base, and moved on.

The Bureau was under a bit of pressure in those days to start living up to its name and actually come up with a colonisation programme, and what they did next was cut some corners. The Bureau's keywords when considering a planet's suitability as a colony were environmental impact. Here, there was no problem. The highest form of animal life was a little smaller than a rabbit and lived in enormous burrow-colonies deep underground, and the most advanced form of plant life was an insanely tough and hardy hedge-thing that grew in sheltered places. People could live here without worrying about displacing native species. It was perfect. The Bureau filled up a transport with colonists and sent them on their way.

The efficiency of the hyperdrive motors back then being what they were, the colonists arrived just after the beginning of the next temperate phase, and the moment they were settled and had time to look around they realised that their new home was going to get a bit cold and windy in about fifteen years' time. Instead of withdrawing the colony, which would have been a huge PR disaster, the Bureau funnelled resources into helping the colonists survive the coming ice-storm season. Half of them died anyway, which was the aforementioned huge PR disaster, but the survivors said something like, "Fuck it, we're not going to let this place beat us," and they were so well-prepared by the time the next hyperweather came along that nobody died. Angels were, by common agreement, some of the craziest people in the known universe.

Lang finished hoovering my sick out of the air and strapped herself back into her control couch. She looked over at me and grinned. "Good, innit?" she said.

"You can't go into hyperdrive inside a gravity well," I said calmly. "The motors won't work."

"Ah." She tapped the side of her nose with a fingertip. "I have magic motors."

"No you don't."

She chuckled. "So. Have I impressed you?"

I burped, tasted sick, heaved, managed to keep what was left of my stomach contents where they were. I said, "Will you tell me how you did that?"

"No," she said. "But I will take you to someone who will. Not that it'll do you any good; only about four people understand it."

I said, "Ms. Lang--"

"Connie."

"Who do you work for, Connie?"

"Have you ever heard," she said seriously, "of Isabel Potter?"

* * * * *

The Writers lived all the way across the system, which with the latest generation of hyperdrive motors took less time to reach than typing the destination coordinates into the navigation computer. It took me longer to sit down in the control couch of One Potato, Two Potato and do up the harness.

The Writers lived in a hollowed-out rock tucked away in the system's pathetically modest asteroid belt. One Potato was a considerably smaller rock--most of our ships were hollowed-out asteroids of varying sizes--and we approached the Writers' vessel like a pebble nudging up against Manhattan. There was a tunnel hidden away in the bottom of one of the many craters on the rock's surface, near the axis at one end; we dropped smoothly into it and emerged in a cavern the size of an aircraft carrier, its tiered walls ranked with hundreds of tugs and ships. I found One Potato a space on one of the ledges, landed us, and floated through the docking tunnel into another, rock-walled tunnel.

As I drifted through the tunnel I felt my inner ears start to assign an up and a down, the rock's rotation providing a semblance of gravity that grew stronger and stronger and drew me down to the tunnel's floor and was eventually enough for me to bounce along. It was only a sixth of a gee or so, but after months in freefall I felt heavy and sluggish.

The tunnel split into two, and then into two again, and again. I kept to the left-hand fork every time, passing side tunnels full of transport containers and powered-down machinery, and bounced along in this way for a couple of kilometres until I came to a rack of bicycles. Cycling in a sixth of a gee of centripetal gravity can be tricky, but I only fell off a couple of times before I reached my destination, a little vestibule walled with Doric columns cut out of native stone, with a simple plain archway on the other side.

I stepped through the archway and out onto short-cropped grass. Before me was a landscape of gently rolling wooded hills and grasslands that faded off into a misty faery distance. To either side, the landscape curved gently away until it eventually hung overhead, obscured by the daylight tube that ran down the axis of the habitat. At my feet, a patch of crushed white stone led off to become a path that wandered away into the landscape. Some distance away, figures were approaching me along the pathway.

I sighed and shook my head. This was what happened when a bunch of Tolkien geeks got the power of life and death over an entire solar system, and I was almost exactly the wrong generation to appreciate it.

The line of figures moving along the white path resolved themselves into about a dozen elves dressed in silver armour and carrying bows and swords. They stopped just in front of me and their leader broke into a huge grin.

"Wotcher, Duke," he said. "Wassup?"

"Got a situation," I told him. "Need to talk to the Council."

His grin went away and he nodded soberly. "Yah, been keeping an eye on that. Council's expecting you."

"Excellent," I said, with more than a touch of irony. "Take me to your leaders."

* * * * *

Isabel Potter was the bogeyman. She was Baba Yaga, the Wicked Witch of the West. I actually once knew someone who invoked her name to make her children go to bed. She was Legend.

She'd started out as a professor of molecular biology at Princeton--bright, overachieving, cultishly popular with her students. Then she had moved into research into gene therapy for congenital conditions, and had made a breakthrough which even now was a closely guarded secret. Whatever it was, she had had the simple, glowing epiphany that the human body was infinitely--and desirably--hackable, and she had begun to hack it.

It was not a good time to be doing stuff like that. The US was being run by what was in effect a right-wing theocracy, which had banned experimentation on the human genome on ethical grounds. After a couple of years of banging her head against a brick wall, Potter had lost patience and simply gone ahead and produced what turned out to be the first of the Kids.

The experiment was a success, but word got out and Potter barely escaped ahead of various law enforcement agencies. On the run with a dozen or so of her graduate students, who would have taken a bullet for her, she finally settled in China, where there were no real qualms about experimenting on anything which took anyone's fancy, and for a decade she thrived. Word began to filter out of Beijing of some very odd variations on the human baseline.

The US authorities have long, bitter memories and they're prone to vindictiveness, and one night a SEAL team parachuted into the heavily guarded compound where Potter lived, took her into custody, and whisked her back to Washington, pour décourager les autres. Some of her students were killed in the operation.

The rest, fuelled by righteous anger, broke Potter out of Federal prison, got her offplanet, and stole a Bureau colony transport by the simple expedient of boarding it and switching on its hyperdrive motors. Which would have been more than enough to win everyone involved a death sentence, probably, but there were more than forty thousand colonists already on the transport, waiting in suspension for a trip to one of the new Bureau worlds.

For more than five hundred years, Isabel Potter and her companions had been at the very top of the Bureau's Most Wanted List, and for more than five hundred years nobody had the faintest idea where they had gone.

* * * * *

The Council was elves and dwarves and hobbits and goblins and God only knows what all else. I hadn't read the right books or seen the right movies to be able to identify them all, but there were lots of Klingons there, too. Attending a Council meeting was like being at the Masquerade at a science fiction convention. Having founded the Colony, the Writers were mostly about having fun, and if that fun involved rewriting themselves as characters from late twentieth-century popular culture, that was okay by me. They mostly left the Colony to run itself, which meant my contact with them was limited. Unfortunately, there were situations where, because they were, after all, the Founders, they were the final arbiters. I'd done this four or five times during my Presidency--although never for a situation as serious as this--and it was always like giving a presentation to an audience of toons.

The stadium where we held the meeting was a big grassy depression surrounded by trees. There was a little knoll at one end with a rough wooden podium on it, and there I stood with a huge infosheet behind me, doing the audiovisual thing. I showed them footage of the probe, told them what Ernie had done, spoke about the apparent failure of the dewline, my assessment of the situation. I laid out my arguments as clearly as anyone could when faced with a massed audience of elves, werewolves, orcs, vampires, ghouls, zombies, Jedi, several iterations of Tom and Jerry, Itchy and Scratchy, and Roadrunner and Coyote, assorted superheroes, too many Darth Vaders to count, and at least two colossal lions. To preserve my sanity and my dignity, I kept my eyes on the ground and talked quickly.

"It's my assessment," I finished, "that this probe represents a clear and present danger. It got past the dewline somehow, which either means the dewline itself is faulty--and we're still assessing that at the moment--or it was designed with the intent to infiltrate systems with passive perimeter defence, which suggests to me that it was looking for us." I looked up, and wondered, not for the first time, what kind of person had themselves rewritten as a zombie. I took a breath.

"You've examined the probe?" asked a Wolverine.

I sighed. There's always one... "As I said in my presentation," I reminded the audience, "the probe's a mess. Its main engine has made it fantastically radioactive. It's so radioactive that, if we were anywhere else, I'd be advising you right now to sue the Bureau for dropping it into the system."

Silence. Tough room. The Writers loved jokes, so long as it wasn't someone else making them.

I said, "Anyway. We can't get near it. In fact, to my mind it's suspiciously radioactive, as if it was deliberately poisoned. Also, Ernie seriously damaged it. If it was carrying stealth technology, we may never be able to reconstruct it."

"It's also old," mused one of the lions. "That design of fission motor dates back hundreds of years."

"Doesn't mean the probe's that old," said a Klingon. "As Duke says, they could have deliberately used a dirty design to stop anybody looking too closely at it."

"Why would they do that?" asked an elf.

"To stop us seeing what kind of stealth tech it's using," said the Klingon. "Duh."

"Fuck off," said the elf. "It was a reasonable question."

Someone else disagreed. Then someone else disagreed with them, and all of a sudden everyone was shouting. I sighed. I'd been here a little over a century and if I had learned nothing else in all that time, it was that very very bright people just love to argue.

I raised a hand for quiet. When that didn't work, I found a gavel on a shelf under the podium and banged that for a while. When that didn't work either, I shouted, "Excuse me!"

That lowered the general volume in the amphitheatre enough for me to start banging the gavel again with some expectation of being heard, and little by little the arguing stopped.

When I had everyone's attention again, I said, "Notwithstanding the probe's radioactive state and the uncertainty of whether it contains stealth and/or surveillance technology, my assessment is that we should look very seriously at enacting Option One."

Complete silence.

I looked out over the expectant faces and I said, "We all knew this was a possibility. The Bureau has never given up looking for us. That's why we have Option One. I'm not saying this lightly. I really think we're in trouble this time."

More silence.

Finally, a voice said from near the front of the crowd, "Thank you, Mr. President. We'll go away and discuss the issue."

"Okay, I said. Thank you."

"Could I have a private word with you, though?"

I felt a thrill of expectation. "Sure."

There was a little bower behind the amphitheatre. The person who joined me there was still recognisably human. She was slim and elegant and red-haired and she seemed to be in her mid-thirties, but you had to constantly remind yourself that nothing in the Colony was how it seemed.

"Mr. President," she said.

"Professor Potter," I said. "Nice to meet you finally."

She smiled. "If I went around personally greeting every new arrival I'd never get anything done."

"It's okay," I told her. "I've only been here a century." And it wasn't as if there was a constant stream of tourists passing through the Colony.

There were a couple of sunloungers on the grass on the other side of the bower. Potter sat down on one and motioned me to sit beside her.

"You do appreciate what you're asking us to consider doing," she said when I was seated.

"As I told you, I'm not suggesting it lightly. I showed my working out as well as I could; can you think of another course of action?"

"Collapsing the habs, loading the populace into ships, going somewhere else."

"Professor, I think it's more than likely that the Bureau has found us. We can't fight them. We have to at least think about making a run for it."

"Can't we?" she pondered. "Fight them, I mean?"

"Well, yes, we can," I allowed. "But there are always going to be more of them than us, with more resources. If we resist they'll eventually just stomp all over us. Lots of people will get hurt."

"I could just give myself up, go quietly."

"With respect, you don't really mean that."

She chuckled sadly. "No," she said. "No, I don't." She looked about her. "I'm rather flattered they're still looking, to be honest. It's been five hundred years."

"For all they know, you've been on a ship with really inefficient motors the whole time," I told her. "Also, they'll want the colonists back."

She looked at me coolly. "You really are rather insubordinate, aren't you," she said.

"Yes, I am."

"I'm rather sorry we didn't meet earlier."

Because most of them had rewritten themselves so radically, it was quite easy to forget how old the Writers actually were, but Potter had remained more or less baseline human, on the outside, anyway. She might have been the oldest person in the galaxy; she had spent much of the first couple of hundred years of her exile in hyperdrive, fleeing through the night on not very efficient motors, but for the last three hundred years she had been here. She looked about thirty, coolly beautiful, but there was something about her eyes that I couldn't quantify, something agelessly capable. She was actually a little scary.

"How do you think the vote will go?" I asked.

"The vote? Oh, that's a foregone conclusion." She sighed. "We're going to fold our tents and light out for the Territories. It's a shame, but as you said, we knew this was coming sooner or later."

"I'm going to need a lot of resources and manpower."

"So are we. Option One originally called for a phased and orderly withdrawal to the first Rendezvous Point within six months of enactment. That was when the Colony was a lot smaller."

"I need to be sure I can trust the dewline," I said. "If the Bureau do enter the system and we don't spot them, it won't matter how orderly the withdrawal is. I need to make that a priority."

"We lost two habs the last time we moved," she reminded me.

"I know."

"I won't let that happen again. These people trust me--they trust us, Mr. Faraday. They're here because they believe in what we're doing, and they rely on us to make the right decisions. I will not let them down."

"With respect, Professor, this conversation is all very well sitting here in a great fuck-off big colony transport that can pop out of the system at a moment's notice, but there are over fourteen thousand, ships, tugs, and assorted transport solutions out there. Maybe half of them are hyperdrive-capable. I need to recall them all to their nearest hab. That's by far the simplest part of Option One, and that alone is going to take us weeks. Months, maybe." And that didn't take into account the dickheads who would decide that they wanted to stay behind. "And I can't give you any reasonable read on security until I can trust the dewline."

"I'll make sure you have all the manpower and resources you need, Mr. President." She stood up. "But as soon as I need them for the withdrawal, I'm taking them back." She looked down at me. "Fair?"

It was the best I could have expected, under the circumstances. "Yes. Fair."

She smiled. "You've done well; I'm proud of you. Now, we all have a lot of work to do. I want daily reports--hourly, if the situation changes."

"Of course."

"With any luck we might be able to get out of here without anyone ever being sure we were here in the first place."

"You don't believe that any more than I do."

She looked a little sad. "No," she said. "I don't."

Copyright © 2017 by Dave Hutchinson

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details