Added By: Weesam

Last Updated: Administrator

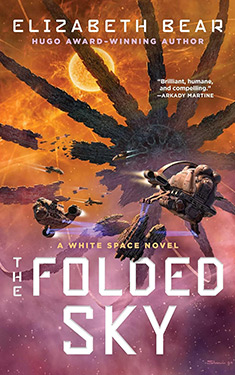

The Folded Sky

| Author: | Elizabeth Bear |

| Publisher: |

Saga Press, 2025 |

| Series: | White Space: Book 3 |

|

1. Ancestral Night |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Information doesn't want to be free. Information wants to vanish without a trace.

Sunya Song's job is to stop that from happening.

She's an archinformist: a specialist historian whose job usually involves sitting at a console at her university job near the Galactic Core, sorting ancient documents and restoring corrupted files.

But now, the research opportunity of a lifetime has sent her--along with her teenage children and alien wife--halfway across the galaxy to preserve the data and aid in the retrieval of the archaeological find of the century: an ancient alien artificial intelligence called Baomind. As vast as a stellar system, the Baomind orbits a dying red giant, and the star's time has nearly ended.

The isolated research station and its small fleet of ships come under attack by fanatic Freeport pirates who believe that artificial intelligence is an abomination that must be destroyed, putting the lives of Sunya and her family at risk.

Tens of thousands of lightyears from home, isolated from all help, Sunya is the only one who can save them all.

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

THE SKY OUTSIDE THE PORTS resembled a brindled jewel. Bands of light alternated with void-black as crumpled space-time hurtled past our ship's stationary warp bubble. Over the past five months I'd watched the patterns grow dimmer and farther apart. We were leaving behind the dense starfields of the galactic core, bars, and arms. We were headed into darkness.

It was an awe-inspiring artifact of the intersection of nature and engineering. I was sick to death of looking at it. The novelty of white space had worn off. Cabin fever was setting in.

Every kid wants to travel in space, right? Well, I'm here to tell you most of it is boring.

Admittedly I was cargo and the ship I was on never let me forget it. We had traveled almost the entire radius of the Milky Way to reach a system-sized archaeological site previous explorers had called the Baomind: a vastly ancient, vastly interesting, sentient artifact swarm left behind by the Koregoi, our forerunners and transcenders as a galactic civilization.

My goal--the proposal that the Synarche had accepted when they authorized my trip out here--was to build a preliminary catalogue of the information held in the Baomind. I wouldn't have time to do much more, I thought--but once we moved it to a safer location and it had reassembled itself, knowing what it knew and what kinds of expertise and experience it could share would be tremendously useful.

Possibly useful enough to win me a spot on the permanent research team.

I'm an archinformist. My name is Dr. Sunyata Song. My friends call me Sunya. My kids call me Mom. My wife, Salvie, calls me Sun.

I had spent the past half year in transit and in preparation. Because I was just a passenger, I had no responsibilities except to exercise, build my algorithms, and catch up on my reading. The crew were glorified long-haul truckers. They were also a docked clade: essentially one person spread out over five bodies. Their name was Chive, and being around them gave me the creeps.

The shipmind was called Dakhira, and he might have offered companionship and conversation. Except he had no use for me at all and was possibly the rudest sentient I'd ever been forced to work around.

Suffice it to say, crew and shipmind were no more thrilled with me at this point than I was with them. Anyway, we were getting close now.

I would have spent more time in my cabin, only it was essentially a rack recessed into the bulkhead, with a walkway alongside the rack exactly one human butt-width (slimmer than mine) wide. I could set the wall to show an outside view, but there were no windows and no place to work.

I was the only passenger on a ship designed to carry an entire research crew, so Dakhira could have reset the space to give me more room and, say, a desk. But that would have required the ship to be something other than a complete and total gnoll.

So I spent most of my time in the lounge or the forward observation deck that doubled as a bridge when the crew was actually navigating. I don't know how I would have survived six months of that nonsense if not for a lot of rightminding.

The rightminding also helped with missing my wife, and Luna and Stavan, my kids. I occasionally felt like a monster for leaving Salvie behind with a couple of teenagers, and I occasionally felt like a monster for the moments when I recollected what it had been like to be footloose and fancy-free. But mostly I just missed them with a dull ache that could have been incredibly distracting if I let it.

And, truth be told, I worried that while I was gone they might discover they didn't need me.

Forward suited me pretty well as long as Dakhira and the Chives were leaving me alone. Once I had gotten my space legs--or lack of legs, maybe--I felt I was as agile as anybody without afthands could hope to be. Over the past months, I had enjoyed floating there amongst the ports and screen walls, letting the universe go by while I processed data. I had asked Dakhira to bring along all the available recordings of Baosong, the complex and beautiful communication protocol the Baomind used to talk to itself and others. Getting a feel for it, letting it integrate in my mind, building parsers and algorithms to sort it was the first step in my preparations to process and preserve as much of its knowledge and history as possible, once we got there.

I thought I was going to have a pretty good jump on it once I got access to the complete databases.

I wasn't a musician or a mathematician, just an archinformist. Which was why I was wearing the recorded memories of a couple of world-class musicians and mathematicians as ayatanas. That was probably part of what was making me feel so trapped: it's rarely pleasant sharing your head with copies of several different strong personalities, especially when they disagree with one another. Disagreement is good: if standard protocol for long-term ayatana use were for everybody to wear the one acknowledged expert in a field, innovation would soon stagnate.

I had also loaded my fox--my internal hardware--with as much Baosong as it would hold. I'd written parsers (90 percent of archinformation is writing parsers) that would assimilate and compare all of it, pick out patterns, and sort information into categories. I hoped this would result in my having the entire logic structure in place by the time we reached the Baostar and I got access to the main body of data.

I should be thinking about the recovery and preservation of information. In the case of a vast constructed intelligence, the recovery and preservation of information was indistinguishable from the recovery and preservation of life. Including engineered life, such as Dakhira. Such as the Baomind.

This was our only chance to study the Baomind in situ. The Baostar was in its senescence, enduring a hospice that would end with its collapse into a black hole. Whether that collapse happened next week or next millennian... well, they were not much different, from the perspective of a star.

Work was under way to evacuate the tesserae to a stable but uninhabited star closer to the Core, white ships hopping back and forth in endless round trips from here to there, the loops of their white coils filled with chips of Baomind. Like swans ferrying cygnets from place to place on their backs, though in this case the cygnets were far older than the swans.

I was no physicist, but I was given to understand that by removing the Baomind we were further destabilizing its primary. The artifact and the star each were life support for the other. The star provided radiation that fueled the Baomind. The Baomind used its gravity-manipulating technology to postpone the star's overdue collapse.

Postpone, not avert. Even the Koregoi couldn't engineer Death away forever. And we were removing an incalculable amount of mass from an unstable system.

Incalculable by me, anyway. The AIs handling logistics probably knew it to a gram.

But that was a problem for when we arrived. In the meantime, it was pleasant to float in Forward, listening to strange harmonics and allowing the parser, a translation protocol, and several recorded experts process them while I monitored the process and made judgment calls. Bands of starlight only flickered past every few seconds now, and I had dimmed the lights. Forward's interior was carpeted with greenery growing in a sterile mesh to help with carbon and water exchange. The effect was something like floating over a lush, green lawn under a very strange sky of stars.

The ambient quality of Baosong meant it was easy to drift along beside it in a meditative state. My human neural biases expected the music to construct a narrative, to build to a climax, but though the intensity rose and fell, it was like the babble of conversation in a crowded room. With the help of my ayatanas I could hear a phrase or motif originate, build harmonics, and propagate through the sound-space in an auditory representation of data being passed in waves through the Baomind, which was so vast it might take three hundred minutes for a single impulse--a thought--to make a circuit of the entire thing.

Phrases originated, propagated, and overlapped in ripples, altering each other as they crossed, amplifying or diminishing. I probably wouldn't have been able to follow it all with my physical ears--it was like music and sound effects echoing around a darkened theater--but I had programmed my fox to provide both visualizations and better-than-nature aural inputs.

I was so immersed in my work that the sharp discovery that someone had drifted up in my blind spot to loom over me made me jerk and scream out loud. The spasm sent me spinning in place until I flung my hands and feet out, slowed my angular momentum, and managed to make contact with the wall, to the detriment of a twining pothos. My palm stung with the impact, but I grabbed onto the mesh and didn't rebound. Pretty good skills for a dirtsider.

I turned my head to yell at whichever Chive had snuck up behind me, only there was no one there.

There was no one else in Forward at all.

"Dakhira, lights up, please."

The compartment flooded with simulated daylight. Every nook and cranny bright, and still no sign of another person.

"Are you malfunctioning?" Dakhira drawled.

I had to intentionally unclench my jaw. "You did that, didn't you?"

"Did what?" The AI was the personification of wounded innocence.

"That was air pressure or subsonics or fiddling with my fox," I said. "You're not haunted. So logically, you made me feel like somebody was creeping up behind me.

The AI chose not to grace that with an answer.

"The only other people on board are the Chives. Your crew. And they aren't here."

"Your human heebie-jeebies are not of my instigation, Dr. Sunyata Song." How could a flat tone sound so scathing? And why did he always have to use my full name and title? Probably because he knew it was annoying. "Perhaps you don't have the experience or focus to manage so many ayatanas. The sensed-presence effect is a known neurological side effect in untrained humans."

I knew he was trying to make me angry, and that knowledge was the only thing that gave me the self-control to tune down my annoyance. "I'm at the end of this Baomind file. Would you extract the next one from the archive, please?"

As if the lights coming up were a signal, two of the crew drifted in from Center. The other three Chives might be asleep in Aft. These two were not quite identical--none of them were exact duplicates, and one of these was male, the other female--but they had matching haircuts and jumpsuits and body language.

"That was the final archive," he said.

I took a deep breath and let it out again. I couldn't count high enough to deal with this. "Dakhira," I said, "where are the rest of the Baosong files?"

"That is all of them."

Revelation dawned, and with it denial. He couldn't possibly have--

I said, "You didn't pack the one thing I specifically told you to pack."

"You obviously didn't need them. You've only just noticed they are missing."

"I only just finished the previous one!"

"Some of us need that space for thinking. The kind of thinking that allows me to navigate without you and the rest of the cargo dying, which I'd think has some value even from your limited perspective. Maybe you should have considered donating half your neurons to the cause. Your species boasts a small degree of neuroplasticity. Once you adapted, you probably wouldn't even miss them."

"How did you manage not to bring the single thing I need in order to do my job?"

He sighed. It's extra insulting when AIs sigh, because they never do it by accident. "Don't get your helicases in a twist, compost. I estimated how much of the archive you would manage to review nearly perfectly, and in less than a dia we'll be at the source. Besides, you have all the packets we picked up from buoys along the way to dig into."

I could work with them, but they would slot into a different part of the pattern I was building, and it annoyed my sense of orderliness.

Fortunately, I had installed an interrupt between my salty language centers and my mouth when I was in grad school. After two more deep breaths, during which I reminded myself that Dakhira was most likely my eventual ride home and that if I filed a complaint against him for creating a hostile environment he'd be the one bringing the packet containing that complaint back to the Synarche, I managed to say, "You mean you thought I would process half the data you provided, and the rest was a buffer, just in case."

The Chives, who had been opening up consoles and ignoring our tiff, burst into their eerie synchronized laughter.

"You have been--" one began; another finished, "--more diligent than he anticipated."

"Don't worry about it," Dakhira condescended. "Even with your truncated lifespan, a few diar of missed work won't set you back too far in the grand scheme."

I had no idea how this insufferable asshole ever made it through quality control into wide release, let alone into a public-facing job.

"I'm going for a walk," I said.

It would have been more satisfying if I could have escaped my cohabitants by doing so.

Imagine if your haunted house had the personality of a really annoying sulky teenager. That was Dakhira on a good day, and I would much rather have been sulked at by my own kids. Doors and drawers worked but were always a little bit sticky. Sliding panels slid aside just a hair slower than expected, then closed too quickly, so one was always stubbing some body part on the edge. The food was always cold or stale, the coffee just a little burnt.

Space isn't infinite but it sure can seem that way when you're trying to get across it. Especially when your driver is a shipmind with a serious attitude problem. He only gets away with being a profound dick because he's very good at his job.

My anger got me past all the annoyances and into the gym. I got my shoes from the locker and strapped myself into the resistance cage. I didn't want to talk to Dakhira, so I called up an immersive environment manually. A nice walk through a volcanic park in a part of Earth called New Zealand.

Sometimes I use files from Rubric, but if they're from anyplace I've ever been, they make me homesick as hell. Honestly, if I could have done this job without leaving behind wife, home, family, pets, and all, I would have just stayed put. The lack of them was an emptiness inside me.

Other people don't take off halfway across the galaxy on their first trip off-planet. They get their toes wet with a few little jaunts first, maybe traveling insystem or visiting a tourist attraction on a nearby world.

Other people might not have to work so hard to prove to themselves that they're not afraid of space, either.

I tried to focus on the exotic alien landscape of humanity's ancestral home. It was beautiful, but it also wasn't holding my attention.

I broke into a jog. The simulation passed by that much faster.

Usually I would exercise while listening to Baosong, but going back over old data felt too much like admitting defeat under the circumstances. I could be a grown-up instead of a sulky adolescent and get to work on the files we'd downloaded from the last marker buoy at which we had changed direction.

Each ship, by protocol, exchanged data and mail with every marker it passed. Ships traveled faster than information because they traveled faster than light. By propagating along the space lanes, sooner or later the mail reached its destination. When the intended recipient read it, their attention triggered a wave-state collapse in the entangled quantum bits embedded in the packet. That in turn terminated any other branches still seeking a path from point A to point B. Tidy, and it saved data space.

How does a packet inside a starship somewhere in white space know that your Aunkle Velma is reading hir birthday card out near Arcturus? Don't ask me; I'm not a physicist. I'm a historian.

Aside from one set of files that only appeared in the marker we'd passed most recently, each of the last three buoys that Dakhira had scraped on our way had some of the data I needed. The relevant files were all the same from buoy to buoy, all recent.

Except... the data from the ship I Span the Empty Deeps wasn't duplicated. And that was unusual.

Perhaps she had taken a different route inbound. Perhaps we had passed her in white space, traveling in opposite directions between waypoints. But no, I checked the telemetry. Her flight plan and date of departure should have put her three buoys Coreward when we passed her, not one.

A chill crawled up my neck and I sensed, again, that eerie presence right at my back. I shuddered, but shook it off.

Should I tell Dakhira about the missing ship? He'd probably be offended; he'd almost certainly already noticed the discrepancy. And I didn't feel like being yelled at again.

Screw it. I switched the walk/jog program to kickboxing and started pummeling an imaginary opponent, pushing against the cage. The rig provides an odd sensation if you're not accustomed to it, like exercising underwater only with gel contact pads to provide calibrated resistance.

It definitely provides a workout, though. After seven minutes my heart was pounding against my ribs and sweat flew off me. In combination with a gene-and-microbiome therapy derived from Earth ground squirrels and pretty good radiation shielding in the form of magnetic bottles and hull design, this kind of exercise allows my fragile species with its tendency toward muscle and bone atrophy and predilection for uncontrolled cell division to travel in space for years without falling apart completely.

And if I imagined my virtual opponent was the physical embodiment of a certain mouthy AI, nobody was going to inform him.

That motivation got me through a strenuous half hour before I panted to a halt. The anger had subsided without any need to adjust my brain chemistry, which made everything feel easier. I freed myself from the cage and floated out, sweat cooling on my skin. My moment of calm lasted exactly as long as it took me to drift to the hatch.

The door didn't open.

"Dakhira," I said, "could you open the door, please?"

He said, "There's exudate all over my exercise cage. You need to sanitize it."

Dakhira was perfectly capable of keeping his own fixtures clean. But if I argued, I might be stuck in here for hours. "Print me some cleaning supplies, then."

A cabinet door popped open on the other side of the gym. Dakhira said, "If you bothered to clean up after yourself, you'd know where they were."

Dakhira must have practiced that cutting tone on a lot of systers to get it so perfectly infuriating.

I snorted. "When I go over there, you're probably going to dissolve the bulkhead and dump me out into white space. So don't think you're catching me by surprise."

"I would not harm you. Or let you come to harm. But I wouldn't expect an organic to understand ethics."

It wasn't so much that I was speechless with fury as that I suspected Dakhira might eventually drive me to murder. I didn't want to have to go around destroying evidence after I deleted the smug, condescending asshole. And the level of invective I was tempted to direct against him at that moment would definitely prove motive, if not means or opportunity.

I wondered if I had the skills to delete him. I might have liked to find out. Dakhira's loathing for humans was legend. I was warned about him before I took this ride, only I didn't believe it could actually be as bad as anyone said and he was the first ship willing to leave, and willing to go without waiting for other passengers who might have distracted me from my work.

Ironically, I thought I'd have more room if I traveled solo. In hindsight, other passengers might have been a blessing.

I collected the disinfectant towels and didn't die, which half surprised me. This close to our destination, I probably had nothing to lose by further antagonizing Dakhira, so I asked, "Why do you carry passengers since you hate organics?"

"Organics treat my people as indentured servants," he said. "You're probably going to do the same thing to the Baomind. It's my duty to try to protect it. So I need to be on the spot."

"I have an obligation to the Synarche, too," I protested. "Society doesn't function if we don't do communal work and create resources for each other!"

"Communal work. Like not leaving your messes for other people?"

"Ugh." I threw the used towels into the collection bin. He'd recycle the molecules and print something else with them.

"Anyway, I'm not leaving you meatforms alone with the oldest, biggest constructed intelligence anybody has ever found. You can't be trusted to treat it fairly."

I bit my lip and directed myself back to the hatch. This time, the door let me through.

Copyright © 2025 by Elizabeth Bear

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details